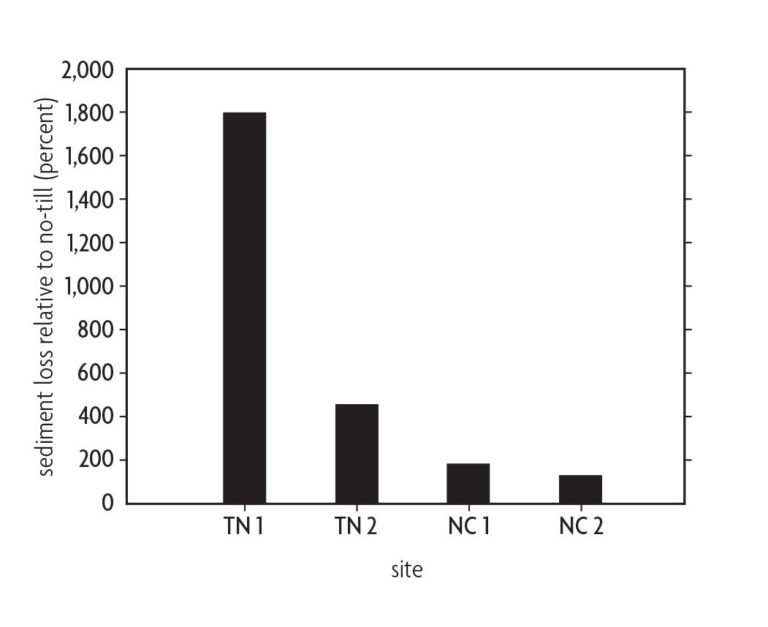

Tillage and residue-management practices have numerous complex effects on soil. These effects are influenced by soil characteristics, tillage and residue-management practices (Table 10.1). Tillage intensity and cover crops influence the amount of soil mixing, site erodibility, nutrient loss, and soil structure, moisture, and temperature. Anything that changes infiltration, leaching, or runoff, or affects crop root development, could change site productivity and thus nutrient needs. On sloping land, erosion control may be the most visible benefit of conservation tillage (Figure 10.1), while enhanced infiltration and improved equipment access may be more important on flat land (Figure 10.2).

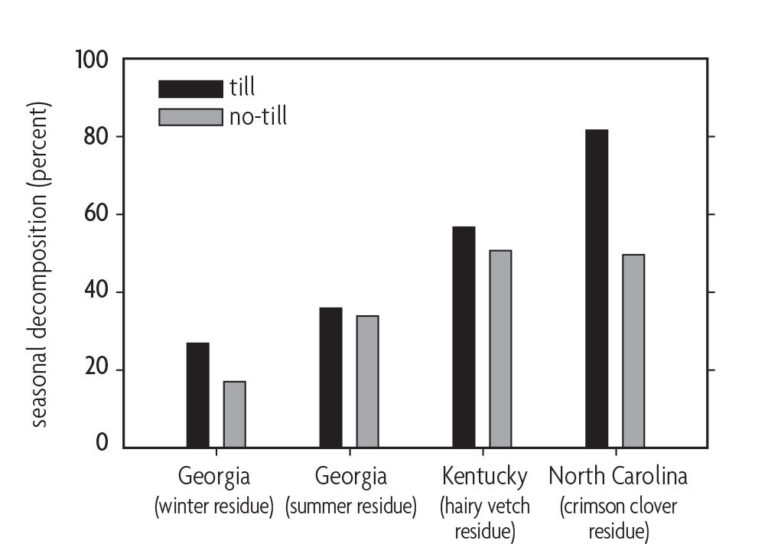

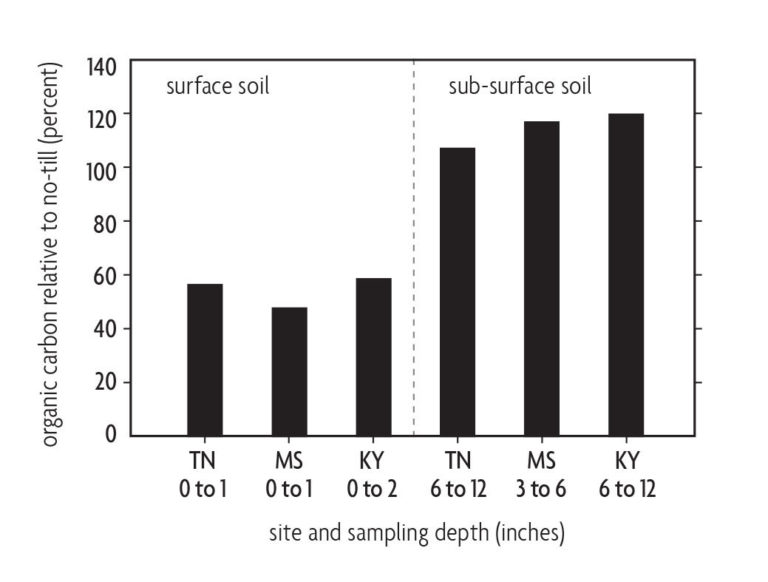

Residue and cover crop decomposition will be slower with less tillage (Figure 10.3), although this primarily influences organic-matter distribution in the soil profile rather than the total amount of organic matter remaining. More organic matter remains on the soil surface with no-till, while tillage incorporates residues deeper into the profile (Figure 10.4). Increasing total soil organic-matter levels is difficult regardless of the tillage system. This is especially true in southeastern sandy Coastal Plain soils due to the generally warm, humid and well-aerated conditions.

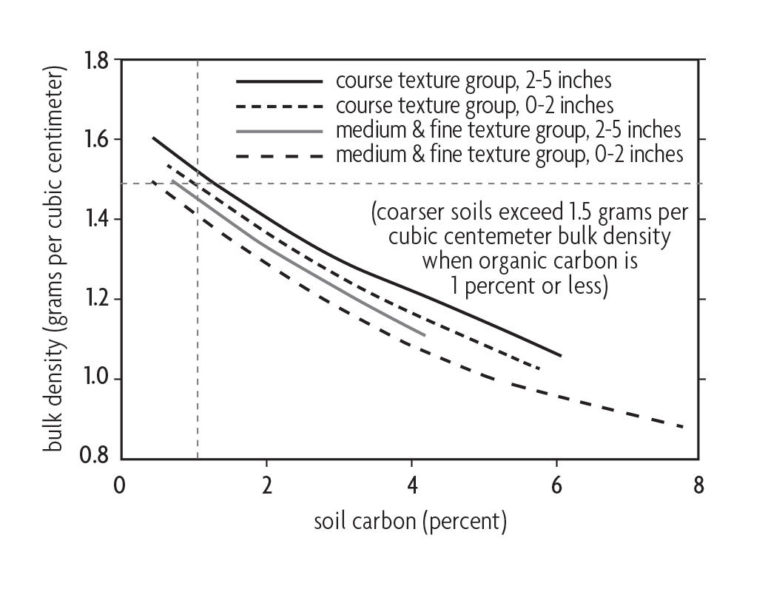

Successful use of conservation tillage requires producers to understand how their soils respond to traffic and reduced tillage, and how to establish crops in surface residues. Continuous no-till has been successful with some soils and rotations. However, some cropping systems, especially continuous cotton and silage corn, and some soils, especially those with low organic matter, experience soil compaction that must be alleviated with in-row subsoiling or strip tillage. Studies from both North Carolina [28] and Australia [5] describe increasing soil bulk densities with no-till where soil organic-matter concentrations are low. As bulk density increases, the soil hardens. In the sandy Coastal Plain soils of North Carolina that have 1 percent or less organic carbon, bulk density was found to exceed 1.5 grams per cubic centimeter with no-till, as shown in Figure 10.5. This is considered too high for successful crop growth because root growth is inhibited. The photographs in Figure 10.6 have the same variety, plant populations and planting date. They show less vigorous growth of soybeans in the no-till plots on a sandy Coastal Plain site [28].

Rotations with winter-grain cover crops may require a combine straw spreader to uniformly distribute residues. Uniformly distributed residues make it easier to achieve the desired seeding depth and seed-soil contact throughout the field for the subsequent crop. To minimize rutting and soil compaction, do not plant or harvest when the ground is too wet. Planting equipment designed for no-till systems is essential for good stand establishment. Use a no-till grain drill or a no-till planter with options for row cleaners and starter fertilizer band placement. When row cleaners are used, adjust them for minimal soil disturbance. These and other practices that contribute to uniform stands increase nutrient-use efficiency since yield is maximized and the rapidly growing crop canopy reduces nutrient losses.