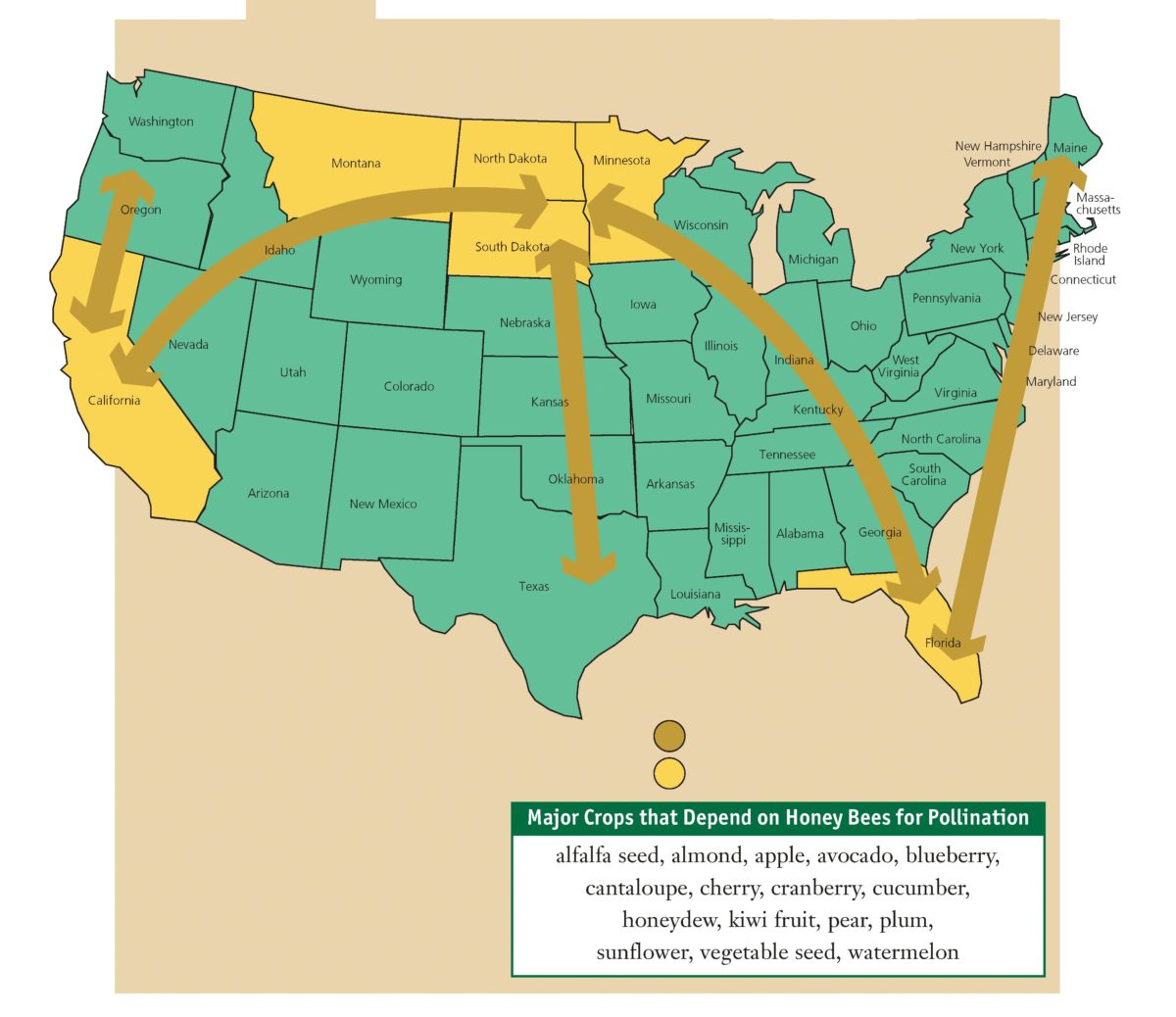

Note: The major honey producing states are shown in yellow. Arrows show the path of some migratory beekeeping operations. For example, beekeepers on the East Coast may move colonies to the Northeast for blueberry and cranberry pollination and a variety of other crops, and to the South to produce honey from citrus. Some beekeepers in the Midwest may move their colonies to California for almond pollination, then return to produce large honey crops from clover, alfalfa, canola, and basswood. Other midwestern beekeepers may move their colonies to Texas and other southern states to produce queen bees and to increase their colony numbers by making “divides.”

An amazing example of the business of pollination comes from the almond industry. Currently, 615,000 acres (~250,000 hectares) of almonds are grown in the central valley of California. This crop is 100 percent dependent on bee pollination; bees must be present for the trees to produce nuts. Growers rent 2 colonies of honey bees per acre (~5 colonies per hectare) to ensure commercial nut set, which means that 1.2 million healthy colonies of honey bees need to be placed in the orchards by mid-February to satisfy pollination requirements. In 2010, it is projected that there will be 750,000 acres (~300,000 hectares) of almonds in bloom, which will require 1.5 million colonies. That is a mind-boggling number, especially considering that an estimated two million colonies are currently available (2008) to be transported for pollination in the United States.

Where do the almond growers obtain all these honey bees? An estimated half-million colonies are located year-round in California, and the rest are trucked in by professional beekeepers from as far away as Florida and Maine. These migratory beekeepers are the unsung heroes of agriculture: They are under extreme pressure to supply sufficient honey bees to meet the pollination demands of today’s large-scale crops (Figure 1.3). Beekeepers love bees, being outdoors, and hard work (Figure 1.2).

Currently, a beekeeper receives up to $150 per colony to pollinate almonds. If a beekeeper moves 2,000 colonies into the orchards, he or she can gross $300,000. That sounds lucrative, but most beekeepers net only five to ten percent of their gross. The extraordinary amount of requisite time, labor, and supplies greatly narrow the profit margin.

What are a beekeeper’s operating costs? It depends largely on fuel costs and whether the bees are being shipped across state lines. Approximately 400 colonies can be placed on one flatbed semi-trailer, depending on how heavy the colonies are. Fuel costs depend on the distance the bees need to be trucked. The bees need to be healthy before, during, and after they are moved.

The logistics and expenses for a beekeeper transporting honey bee colonies from out of state to the California almond orchards are more complicated than for in-state beekeepers (Figure 1.4). First, California requires an apiary inspector from the state Department of Agriculture to certify that the colonies are disease free before they can enter the state. Certification fees vary from state to state. For example, inspectors check bee shipments for imported fire ants. Loads of bees can be rejected if they contain the ants on the underside of pallets or anywhere on the equipment.

Another major expense is incurred if the beekeeper decides to pay someone to truck the bees to California and then someone else to “bee-sit” the colonies. Sometimes the beekeeper and his family move to California, which also involves a host of potentially costly and complex logistical decisions, such as two homes and enrolling children in two schools. In both cases, the colonies may be stockpiled in one or more locations, sometimes with 1,000 colonies in one lot waiting to be moved into the almonds. The colonies must be given supplemental feedings of sugar syrup and pollen substitute to keep bees nourished and well populated until almond bloom.

What is the gain to the almond grower? Everything. Without bees, there are no nuts. One estimate says almond growers spend about 20 percent of their operating budgets (variable farming costs) on renting bees for pollination. These costs seem like a small price to pay given the alternative without bees. As almond acreage increases, more bee colonies will need to be trucked in from all points to satisfy a demand that is beginning to far outpace supply. In recent years, beekeepers have started importing “package bees” (mini-starter colonies) from Australia, which means we are now importing the service of pollination. In our modern landscape, economics is driving nature—but with diminishing returns. The potential importation of bee diseases and susceptible bee stocks from other countries, for example, creates a murky economic forecast.

Not too many years ago, when orchards were smaller, bees could build up strength on the high-quality protein of almond pollen. The bees would grow naturally into full-sized colonies by the time the almonds finished blooming three to four weeks later. Then the colonies would be strong enough to move into citrus orchards to make a crop of orange blossom honey. Now that almond growers only pay full price for full strength by the bloom’s start, the almond market is setting an unsustainable rhythm for many of our nation’s honey bees. If we’re not careful, the business of pollination can drive our pollinators out of the business of life.

Profile of a Migratory Beekeeping Operation

Woodworth Honey and Bee Co. had its roots in Iowa in 1937 when Wendell (Woody) Woodworth caught a swarm of bees. In 1955, the Woodworths moved to North Dakota with 400 colonies in tow. For seven years, they maintained bees in North Dakota year-round and replaced colo nies that died during the long hard winter with “package bees” purchased from California. In 1962, Woody began moving his colonies to Idabel, Okla. for the winter, and in 1972 moved his operation even deeper south to Nacogdoches, Tex., where the early spring allowed him to increase the number of colonies and raise new queen bees before bringing them back to North Dakota to make honey in the summer. By 1979, Woody had 6,000 colonies. He sold one-third of the colonies to one of his sons and another third to his son, Brent, and Brent’s wife, Bonnie, keeping the remainder for himself. In 1991, Brent and Bonnie took their first load of bees to California to pollinate almonds.

Today, Brent and Bonnie have 3,800 colonies and their operation is run almost exclusively between North Dakota and California. They pay a professional trucker to haul 3,200 colonies to California in October and November. The colo nies are situated in the Central Valley in holding apiaries some- times containing thousands of colonies. They must provide supplementary feedings of sugar syrup and pollen and medications to control diseases and mites so colonies are strong enough for almond pollination by mid-February.

When the almonds finish blooming in late March, Brent and Bonnie used to ship 6 to 8 loads of bees (at around 400 to 450 colonies per load) to Yakima Valley in Washington to pollinate apples. But the apple growers wanted the bees moved out as soon as the apples stopped blooming in early April, too early to move colonies back to cold, flowerless North Dakota. So now they ship only two loads to Washington and maintain the bulk of their colonies in Central California where they split their colonies to introduce new queens and increase colony numbers before trucking them back to North Dakota in early May. They produce honey during the summer in North Dakota, primarily from clover, alfalfa and canola, averaging around 125 pounds per colony (~57 kilograms per colony). They sell their honey to Golden Heritage Foods, where it is bottled and retailed. The bees are treated for diseases and mites, and by late October are trucked back to California to repeat the cycle.

The Woodworths estimate they net around 10 percent of their gross. In recent years, 65 to 70 percent of their income has come from pollination, the rest from honey. In former years, it was the opposite. Since 2000, however, the price per colony for pollinating almonds tripled and their business followed the boom and bloom. Their biggest expense is labor: It is difficult to find people willing and able to put up with beekeeping’s hard work and stings.

The Woodworths are adamant about their biggest challenge: ensuring their colonies are populous and healthy enough by mid-February to meet almond growers’ criteria. Bees’ natural tendency is to hunker down for winter and build up colony strength cautiously in spring until flowers are in full bloom. Nowadays, almond growers pay top dollar only if colonies have more than eight frames of bees per colony by mid-February. Bees must be stimulated early with supplemental feedings to reach that kind of strength at that time of year.