Where no kind of manure is to be had, I think the cultivation of lupines will be found the readiest and best substitute. If they are sown about the middle of September in a poor soil, and then plowed in, they will answer as well as the best manure.

—Columella, 1st century, Rome

Cover crops have been used to improve soil and the yield of subsequent crops since antiquity. Chinese manuscripts indicate that the use of green manures is probably more than 3,000 years old. Green manures were also commonly used in ancient Greece and Rome. Today, there is a renewed interest in cover crops, and they are becoming important parts of many farmers’ cropping systems.

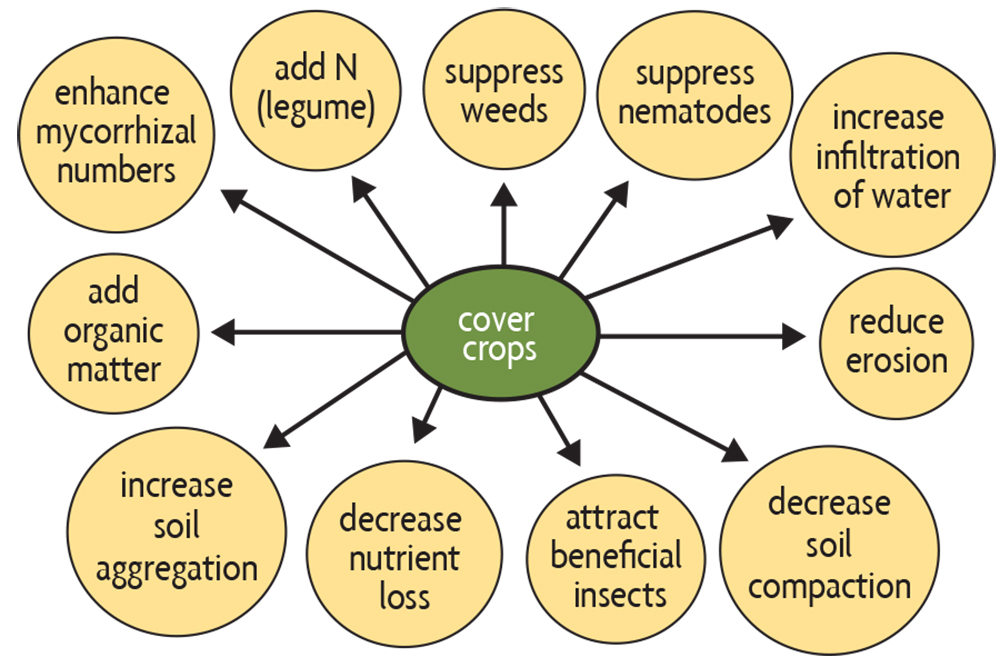

A cover crop is usually grown with multiple objectives. One important goal is to protect and improve the soil with living vegetation during a time of the year when it would otherwise be bare, minimizing runoff and soil erosion, with green leaves intercepting precipitation and lessening its impact, and with living roots holding on to the soil. But cover crops can also have many other benefits: Using the sun’s energy and CO2 from the atmosphere, they increase soil organic matter with their roots and surface residue; protect nitrate from leaching; increase the amount of soil nitrogen (especially with legumes); break up soil compaction; provide habitat for beneficial organisms; and promote mycorrhizal fungi presence for the following crop.

Cover crops are usually killed on the surface or incorporated into the soil before they mature. (This is the origin of the term green manure.) Since annual cover crop residues are usually low in lignin content and high in nitrogen, they typically decompose rapidly in the soil.

Benefits of Cover Crops

Cover crops provide multiple potential benefits to soil health and to the following crops, while also helping to maintain cleaner surface water and groundwater (Figure 10.1). They prevent erosion, improve soil physical and biological properties, supply nutrients to the following crop, suppress weeds, improve soil water availability, and break pest cycles. Some cover crops are able to break into compacted soil layers, making it easier for the following crop’s roots to more fully develop. The actual benefits from a cover crop depend on the species and productivity of the crop you grow and how long it’s left to grow before the soil is prepared for the next crop. In this chapter we focus on the principles of cover cropping, which are more comprehensively discussed in a companion book by the same publisher, SARE, titled Managing Cover Crops Profitably.

Purposes of Cover Crops

The term “cover crop” refers generally to plants that are grown but not harvested. While this term is used generally, different types of plants are grown as cover crops to achieve a number of primary purposes:

Catching and cycling nutrients: typically grasses such as cereal rye and oats. Especially useful in high-nutrient environments.

Fixing nitrogen via symbiotic relationship with Rhizobium bacteria (green manures): typically legumes (e.g., hairy vetch and red clover). Especially useful on organic farms or by others who want to “grow” their own nitrogen.

Smothering weeds: typically competitive, fast-growing species (e.g., buckwheat, sorghum-sudangrass, cereals). Especially useful when weed control is a challenge.

Biofumigating pests with glucosinolates and isothiocyanates: typically brassicas (e.g., mustards and radishes). Especially useful when growing disease-susceptible crops with limited chemical control.

Loosening compacted soil: typically strong-rooted crops (e.g., cereal rye, radishes, hairy vetch, alfalfa). Especially useful to improve a degraded soil.

Growing biomass and organic matter: typically fast-growing crops (e.g., sorghum-sudangrass, cereal rye, sunn hemp). Especially useful when soils are low in organic matter or when you aim to capture carbon.

Providing cover for the soil surface: typically crops that establish quickly during the off season to protect the soil, like rye or oats in cool climates.

Plant ecologists separate these into canopy functions (where benefits are primarily derived from the aboveground biomass) and root functions (where benefits are from the belowground biomass), and the selection of a cover crop may be based on the specific desired traits. If there are particular problems that need to be addressed, it certainly influences the choice of cover crops. However, most farmers grow cover crops specifically because of their multiple benefits (Figure 10.1).

Organic matter. Grass cover crops are more likely than legumes to increase soil organic matter. The more surface residue and roots provided to the soil, the better the effect on soil organic matter. In that regard, we generally don’t fully appreciate their rooting systems unless we dig them up because some cover crops grow as much or more biomass underground than above, thereby directly benefiting the soil.

Good production of hairy vetch or crimson clover cover crops may yield from 1 1/2 to more than 4 tons of dry weight per acre if allowed to grow long enough. Likewise, if a vigorous grass cover crop like cereal rye is grown to maturity, it can produce 3–5 tons of residue. However, the amount of residue produced by an early terminated cover crop may be very modest, as little as half a ton of dry matter per acre. While small cover crop plants add some active organic matter, they may add little to long-term build-up of soil organic matter if not enough root growth and residue are allowed to develop.

A five-year experiment with clover in California showed that cover crops increased organic matter in the top 2 inches from 1.3%–2.6% and in the 2- to 6-inch layer from 1%–1.2%. Researchers found, when the results of many experiments were examined together, that including cover crops led to an organic matter increase of 8.5% over original levels and an increase of soil nitrogen by 12.8%. The longer the cover crop grows and the less tillage that is used, the greater the increase in soil organic matter. In other words, the beneficial effects of reduced tillage and cover cropping can be additive, and the combination of practices has greater benefits than using them individually. Low-growing cover crops that don’t produce much organic matter, for example, cereal rye that’s killed before it has much chance to grow in the spring, may not be able to counter the depleting effects of intensive tillage. But even if they don’t significantly increase organic matter levels, cover crops help prevent erosion and add at least some residues that are readily used by soil organisms.

Beneficial organisms. Cover crops help maintain high populations of mycorrhizal fungi during the period between main crops and thereby provide a biological bridge between cropping seasons. The fungus also associates with almost all cover crops (except brassicas), which helps maintain or improve inoculation of the next crop. (As discussed in Chapter 4, mycorrhizal fungi help promote the health of many crop plants in a variety of ways and also improve soil aggregation.)

Cover crop pollen and nectar can be important food sources for predatory mites and parasitic wasps, both of which are important for biological control of insect pests. A cover crop also provides good habitat for spiders, and these insect feeders help decrease pest populations. Use of cover crops in the Southeast has reduced the incidence of thrips, bollworm, budworm, aphids, fall armyworm, beet armyworm and white flies.

Earthworm populations may increase markedly with cover crops, especially if combined with no-till. Aggressive tillage harms earthworm populations and destroys their burrowing channels—as well as those from old roots—that reach the surface, reducing infiltration during intense rainfall.

Farmers Say Cover Crops Help the Bottom Line

A 2019–2020 national cover crop survey, which included perspectives from 1,172 farmers representing every U.S. state, found new insights into farmer experiences with cover crops. Most producers, working with their seed dealers, are finding ways to economize on cover crop seed costs, with 16% paying only $6–$10 per acre for cover crop seed, 27% paying $11–$15 per acre, 20% paying $16–$20 per acre, and 14% paying $21–$25 per acre. Only about one-fourth were paying $26 or more per acre.

This survey was conducted annually beginning in 2012 (except for 2018–2019). On average, reported yields were higher as a result of planting cover crops in all years, and most notably in the drought year of 2012 when soybean yields were improved by 12% and corn yields were 10% better. Yield gains were more modest in the wet year of 2019, when the average increase was 5% for soybeans and 2% for both corn and wheat. Farmers also reported significant savings on fertilizer and/or herbicide production costs in the 2019–2020 survey for the following crops:

- soybeans: 41% saved on herbicide costs and 41% on fertilizer costs

- corn: 39% saved on herbicide costs and 49% on fertilizer costs

- spring wheat: 32% saved on herbicide costs and 43% on fertilizer costs

- cotton: 71% saved on herbicide costs and 53% on fertilizer costs

In this survey, 52% of farmers “planted green” into cover crops on at least some of their fields. (“Planting green” is the term for seeding a cash crop into a standing cover crop and terminating the cover crop soon after.) Of those, 71% reported better weed control and 68% reported better soil moisture management, with 54% indicating that cover crops allowed them to plant earlier.

Of the horticulture producers surveyed, 58% reported an increase in net profit. Only 4% observed a minor reduction in net profit, and none reported a moderate loss in net profit.

Survey participants indicated an increase of 38% in land devoted to cover crops over the previous four years and the use of a range of cover crop seed and mixes to address their individual needs. This survey showed many positive aspects of cover crop integration and that farmers continue to find benefits to their use.

Source: CTIC-SARE-ASTA National Cover Crop Survey 2019–2020 (www.sare.org/covercropsurvey)

Selecting Cover Crops

Before growing cover crops, you need to ask yourself some questions:

- What are my goals in planting cover crops?

- What cover crops should I plant?

- When and how should I plant the cover crops?

- When should the cover crops be killed or incorporated into the soil?

- What is my next cash crop and when should it be planted?

When you select a cover crop, you should consider the soil conditions, climate and what you want to accomplish by answering these questions:

- Is the main purpose to add available nitrogen to the soil, or to scavenge nutrients and prevent loss from the system? (Legumes add N; other cover crops take up available soil N.)

- Do you want your cover crop to provide large amounts of organic residue?

- Do you plan to use the cover crop as a surface mulch or to incorporate it into the soil?

- Is erosion control in the late fall and early spring your primary objective?

- Is the soil very acidic and infertile, with low availability of nutrients?

- Does the soil have a compaction problem? (Some species, such as sudangrass, sweetclover and oilseed (forage) radish, are especially good for alleviating compaction.)

- Is weed suppression your main goal? (Some species establish rapidly and vigorously, while some also chemically inhibit weed seed germination.)

- Which species are best for your climate? (Some species are more winter hardy than others.)

- Will the climate and waterholding properties of your soil cause a cover crop to use so much water that it harms the following crop?

- Are root diseases or plant-parasitic nematodes problems that you need to address? (Cereal rye, for example, has been found to suppress a number of nematodes in various cropping systems. Brassica cover crops may also reduce populations of certain nematodes.)

In most cases, there are multiple objectives and multiple choices for individual cover crops and for cover crop mixes.

Types of Cover Crops

Many plant species can be used as cover crops. Legumes and grasses (including cereals) are the most extensively used, but there is increasing interest in brassicas (such as rapeseed, mustard and oilseed radish, which is also known as forage radish) and continued interest in summer cover crops, including buckwheat, millets and summer legumes such as cowpeas and sunn hemp. Some of the most important cover crops are discussed below.

Legumes

Leguminous plants are often very good cover crops. Summer annual legumes, usually grown only during the summer, include soybeans, cowpeas and sunn hemp. Winter annual legumes that are normally planted in the fall and counted on to overwinter include winter field peas (such as Austrian), crimson clover, hairy vetch, Balansa clover and subterranean clover. Crimson clover reliably overwinters in hardiness zone 6 and farther south, and sometimes in zone 5. Winter peas have a similar region of adaptation as crimson clover, although it might be usable a little farther north if planted early enough. Berseem clover will overwinter only in zones 8 and above. Hairy vetch is able to withstand fairly severe winter weather. Balansa clover is still being evaluated in colder regions but has in some cases overwintered in zone 5. Sweet yellow clover is an example of a biennial legume, while perennial legumes include red clover, white clover and alfalfa. Crops usually used as winter annuals can sometimes be grown as summer annuals in cold, short-season regions. Also, summer annuals that are easily damaged by frost, such as cowpeas, can be grown as a winter annual in the deep southern United States.

One of the main reasons for selecting legumes as cover crops is their ability to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and add it to the soil. But legumes need to be grown later in the spring—typically until a few weeks after cereals elongate—to reach the early flowering stage and achieve near-maximum nitrogen fixation. Legumes that produce a substantial amount of growth, such as hairy vetch, crimson clover, red clover and Austrian winter peas may supply over 100 pounds of nitrogen per acre to the next crop if allowed to grow to the flowering stage or longer. Other legumes may supply considerably less available nitrogen. Legumes also provide other benefits, including attracting beneficial insects, helping control erosion and adding organic matter to soils.

Inoculation. If you grow a legume as a cover crop, don’t forget to inoculate seeds with the correct nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Different types of rhizobial bacteria are specific to certain crops. There are different strains for alfalfa, clovers, soybeans, beans, peas, vetch and cowpeas. Unless you’ve recently grown a legume from the same general group you are currently planting, inoculate the seeds with the appropriate commercial rhizobial inoculant before planting. The addition of water to the seed-inoculant mix, just enough to moisten the seeds, helps the bacteria stick to the seeds. Plant right away, so the bacteria don’t dry out. Inoculants are readily available only if they are commonly used in your region. It’s best to check with your seed supplier a few months before you need the inoculant, so it can be specially ordered if necessary. Keep in mind that the “garden inoculant” sold in many garden stores may not contain the specific bacteria you need. Be sure to find the right one for the crop you are growing and keep it refrigerated until used.

Winter Annual Legumes

Crimson clover is considered one of the best cover crops for areas with mild climates, like the southeastern United States and the southern Plains, such as Oklahoma and parts of Texas. Where adapted, it grows in the fall and winter, and matures more rapidly than most other legumes. It also contributes a relatively large amount of nitrogen to the following crop. Because it is not very winter hardy, crimson clover is not usually a good choice in hardiness zones 4 or colder, and it can be marginal in zone 5 (snow cover and/or early planting can help with winter survival). Crimson clover survival can also suffer from poorly drained soil conditions. In northern regions, crimson clover can be grown as a summer annual, but that prevents an economic crop from growing during that field season. Varieties like Chief, Dixie and Kentucky Select are somewhat winter hardy if established early enough before winter. Crimson clover does not grow well on high-pH (calcareous) or poorly drained soils.

Field peas are grown in colder climates as a summer annual and as a winter annual over large sections of the South and California. They have taken the place of fallow in some dryland, small-grain production systems. Austrian winter peas (bred for winter hardiness) and Canadian field peas (bred for good spring growth) tend to establish quickly and grow rapidly in cool moist climates, producing a significant amount of residue: 2 1/2 tons or more of dry matter. They fix plentiful amounts of nitrogen, from 100–150 or more pounds per acre. Austrian winter peas will perform best as a winter cover crop if seeded in early fall.

Hairy vetch is winter hardy enough to grow well in areas that experience hard freezing, and it can be planted later than most other legumes. Where adapted, hairy vetch produces a large amount of vegetation and has an impressive root system (Figure 10.2). It fixes a significant amount of nitrogen, thereby contributing 100 pounds of nitrogen per acre or more to the next crop. Hairy vetch residues decompose rapidly and release nitrogen more quickly than most other cover crops. This can be an advantage when a rapidly growing, high-nitrogen-demand crop follows hairy vetch. Hairy vetch will do better on sandy soils than many other green manures, but it needs good soil potassium levels to be most productive. Where wheat is part of the rotation, hairy vetch should be avoided, as hairy vetch may volunteer in the wheat, and the seed sizes are similar enough to make it hard to separate the vetch seed from the wheat seed during harvest.

Subterranean clover is a warm-climate winter annual that, in many situations, can complete its life cycle before a summer crop is planted. When used this way, it doesn’t need to be suppressed or killed and does not compete with the summer crop. If left undisturbed, it will naturally reseed itself from the pods that mature belowground. Because it grows low to the ground and does not tolerate much shading, it is not a good choice to interplant with summer annual row crops. Balansa clover is a new winter annual clover getting some use. The exact extent of its winter hardiness is still a question, and it is currently recommended for growing in zone 5 and farther south. It produces excellent spring growth, but because Balansa clover is a relatively new cover crop species, some small-scale testing for various uses may be appropriate for your location, including evaluation of how it does in mixes.

Summer Annual Legumes

Berseem clover is grown as a summer annual in colder climates. It establishes easily and rapidly and develops a dense cover, which makes it a good choice for weed suppression. It’s also drought-tolerant and regrows rapidly when mowed or grazed. Berseem has the advantage of being unlikely to cause bloat in grazing livestock. It can be grown in mild climates during the winter. Some newer varieties have done very well in California, with Multicut outyielding Bigbee. Frosty is another new berseem clover introduction that is supposed to have improved cold tolerance and is able to be cut multiple times in a season.

Cowpeas are native to Central Africa and do well in hot climates. The cowpea is, however, killed by even a mild frost. It is deep rooted and is able to do well under droughty conditions. It usually does better on low-fertility soils than crimson clover. Cowpeas can perform well in mixes with summer grass cover crops such as pearl millet or sorghum-sudan. The most common variety of cowpeas for cover crop use is the iron clay type.

Sunn hemp is a warm-season tropical legume that grows vigorously as a summer legume for much of the United States; it is also a popular inter-seasonal cover crop in the tropics. Sunn hemp can grow from several feet to as much as 7 feet tall and is used frequently in mixes with other summer cover crops. It greatly reduces soybean cyst nematode populations and is a good nitrogen fixer. Sunn hemp has been noted as a summer cover that deer like to browse, which can be a positive or negative depending on the goals for cover crop use. Soybeans, usually grown as an economic crop for their oil- and protein-rich seeds, can serve as a summer cover crop if a farmer has leftover seed and if allowed to grow only until flowering. They require a fertile soil for best growth. As with cowpeas, soybeans are killed by frost. If grown to maturity and harvested for seed, they do not add much in the way of lasting residues or nitrogen.

Soybeans, usually grown as an economic crop for their oil- and protein-rich seeds, can serve as a summer cover crop if a farmer has leftover seed and if allowed to grow only until flowering. They require a fertile soil for best growth. As with cowpeas, soybeans are killed by frost. If grown to maturity and harvested for seed, they do not add much in the way of lasting residues or nitrogen.

Velvet beans (mucuna) are widely adopted in tropical climates. It is an annual climbing vine that grows aggressively to several feet high and suppresses weeds well (Figure 10.3). In a velvet bean–corn sequence, the cover crop provides a thick mulch layer and reseeds itself after the corn crop. The beans themselves are sometimes used for a coffee substitute and can also be eaten after long boiling. A study in West Africa showed that velvet beans can provide nitrogen benefits for two successive corn crops.

Lablab beans (also called hyacinth beans) are another tropical legume being evaluated as a cover crop in the Southeastern U.S. Once established, they grow quickly in hot weather and can produce vines several feet long. Given their viney, climbing growth habit, they might be best paired with an upright grass cover like pearl millet or sorghum-sudan. As with other warm season legumes, they are killed by a light frost.

Similar tropical cover crops include Canavalia and Tephrosia, which can also be used as mulches after maturing. Pigeon peas are yet another tropical legume that may have some potential as a cover crop.

Biennial and Perennial Legumes

Red clover is vigorous, shade tolerant, winter hardy, and can be established relatively easily. It is commonly interseeded in early spring with small grains. Because it starts growing slowly, there is minimal competition between it and the small grain. Red clover also successfully interseeds with corn in the Northeast if the herbicides used do not have significant residual activity.

Sweet clover (yellow blossom) is a reasonably winter hardy, biennial, vigorous growing crop with an ability to get its roots into compacted subsoils. It is able to withstand high temperatures and droughty conditions better than many other cover crops. Sweet clover requires a soil pH near neutrality and a high calcium level; it does poorly in wet, clayey soils. As long as the pH is high, sweet clover is able to grow well in low-fertility soils. While it is sometimes grown for only a year, a good use for this legume is to allow it to flower and complete its life cycle in the second year, when it produces a large amount of biomass. Like red clover, a typical way that sweet yellow clover has been used is to overseed it into winter wheat in March, then let it grow after wheat harvest until the following spring. When used as a green manure crop, it is incorporated into the soil before full bloom, especially when followed by early spring corn planting.

Alfalfa is not used as a cover crop, but growing it for multiple years as part of a rotation provides some of the same benefits. It improves soil aggregation and water infiltration, and breaks up compacted layers through its deep taproot (Figure 10.2). It also adds significant amounts of carbon and nitrogen to the soil. Following a three-year stand of alfalfa, there should be sufficient nitrogen for most crops for the next year, along with more N than might otherwise be present in the subsequent year or two. It is best grown on well-drained soils that are near neutral in pH and high in fertility. Alfalfa is commonly interseeded with small grains, such as oats, wheat and barley, and it grows after the grain is harvested.

White clover does not produce as much growth as many of the other legumes and is also less tolerant of droughty situations. (New Zealand types of white clover are more drought tolerant than the more commonly used ladino and Dutch white clovers.) However, because it does not grow very tall and is able to tolerate shading better than many other legumes, it may be useful in orchard-floor covers or as a living mulch. White clover has been evaluated for early summer interseeding into corn, but its survival in corn is often not as good as more shade-tolerant species such as annual ryegrass. White clover is also a common component of intensively managed pastures.

Grasses

Commonly used grass cover crops include the annual cereals (rye, wheat, triticale, barley oats), annual or perennial forage grasses such as ryegrass, and warm-season grasses such as sorghum-sudangrass. Grasses, with their fibrous root systems, are very useful for scavenging nutrients, especially nitrogen, left over from a previous crop. They tend to have extensive root systems (Figure 10.4), and some establish rapidly and can greatly reduce erosion. In addition, they can produce large amounts of residue and a large amount of roots. Both the residue and the roots can help add organic matter to the soil. The aboveground residue also can help suppress weed germination and growth.

A problem common to all the grasses is that if you grow the crop to maturity for the maximum amount of residue, you reduce the amount of available nitrogen for the next crop. This is because of the high C:N ratio (low percentage of nitrogen) in grasses near maturity, which ties up nitrogen when decomposing after termination, especially when plowed under. This problem can be avoided by killing the grass early or by adding extra nitrogen in the form of fertilizer or manure. Another way to help with this problem is to supply extra nitrogen by seeding a legume-grass mix.

Cereal rye, also called winter rye, is very winter hardy and easy to establish. Its ability to germinate quickly, together with its winter hardiness, means that it can be planted later in the fall than most other species, even in cold climates. Decomposing residue of cereal rye has shown to have an allelopathic effect, which means that it can chemically suppress germination of small broadleaf weed seeds. It grows quickly in the fall and also grows readily in the spring (Figure 10.5). It is often the cover crop of choice as a catch crop and also works well with a roll-crimp mulch system, in which the cover crop is terminated by rolling and crimping while the cash crop (for example, soybeans) is no-till planted or transplanted into the resulting mulch (see Figure 16.10).

Triticale, a cross between wheat and rye, is almost as winter hardy as cereal rye. It is also easy to establish and has good production of spring vegetation and roots (Figure 10.4), though is somewhat shorter than cereal rye. It can be used for fall or spring grazing. If triticale does go to seed, it is easier to control than many other cover crops that might be grown singly or in a cover crop mix.

Oats are another popular cover crop. Many farmers like to use spring oats for fall cover crop planting because they will not overwinter and thus don’t need spring termination. Summer or fall seedings, usually planted about a month before the last seeding date for cereal rye, will winterkill under most cold-climate conditions. This provides a naturally killed mulch the following spring and may help with weed suppression. As a mixture with one of the clovers, oats provide some quick cover in the fall. Oat stems help trap snow and conserve moisture, even after the plants have been killed by frost. There are oat types that can overwinter in mild climates, such as winter oats or black oats. Black oats, which are a different species of oats compared to spring oats, are popular in no-till systems in South America, where crops such as soybeans are planted into the oat mulch. In the Midwest, black oats often get more fall growth than spring oats, but the seed of black oats can be harder to find and more expensive (note that they are also black-seeded winter oats, which are not true black oats).

Annual ryegrass (not related to cereal rye) grows well in the fall if established early enough. It develops an extensive root system (Figure 10.4) and therefore provides very effective erosion control while adding significant quantities of organic matter. The roots may grow 3–4 feet deep even when aboveground growth is 6 inches or less. Annual ryegrass may winterkill in cold climates. Some caution is needed with annual ryegrass: because it requires a careful approach to termination, it may become a problem weed in some situations.

Sudangrass and sorghum-sudan hybrids are fast growing summer annuals that produce a lot of growth in a short time (Figure 10.4). Because of their vigorous nature, they are good at suppressing weeds. If they are interseeded with a low-growing crop, such as strawberries or many vegetables, you may need to delay seeding so the main crop will not be severely shaded. They have been reported to suppress plant-parasitic nematodes and possibly other organisms, as they produce highly toxic substances during decomposition in soil. Sudangrass is especially helpful for loosening compacted soil. It can also be used as a livestock forage and so can do double duty in a cropping system with one or more grazings and still provide many benefits of a cover crop. If grazing is not an option, periodic mowing helps to control excessive sudangrass stem growth and residue management issues. Mowing also stimulates root development, leaving more belowground residue. Dwarf and brown midrib (low lignin) varieties of sorghum-sudangrass are available and might be considered for cover cropping.

Millets are another group of summer annual grasses used as cover crops. There are actually several different plant species that are called millets, from different regions of the world. The two most commonly used as cover crops in the United States are pearl millet (from Africa) and foxtail millet (from Asia). Forage types of pearl millet can be tall, vigorous crops similar to sorghum-sudan and are drought tolerant. Foxtail millet is also drought tolerant and a fast maturing cover crop, sometimes used in mixes or after vegetable crops.

Other Crops

Buckwheat is a summer annual that is easily killed by frost (Figure 10.5, right). It will grow better than many other cover crops in low-fertility soils but is less tolerant of compacted soils. It also grows rapidly and completes its life cycle quickly, taking around six weeks from planting into a warm soil until the early flowering stage. Buckwheat can grow more than 2 feet tall in the month following planting. If planted in early summer, it may get 3–4 feet tall at maturity but will stay shorter with late summer planting. It competes well with weeds because it grows so fast and, therefore, is sometimes used to suppress weeds following an early spring vegetable crop. It has also been reported to suppress important root pathogens, including Thielaviopsis and Rhizoctonia species. It is possible to grow more than one crop of buckwheat per year in warmer regions. Its seeds are not “hard” and do not persist for multiple years in the soil, but it can reseed itself and become a volunteer weed. Mow, roll, or till it before seeds develop to prevent reseeding. On the other hand, self-seeding can be taken advantage of, and if using tillage, work with a shallow pass with harrows.

Buckwheat grown for grain … occupies the land only during three months of the year, and which consequently figures in the first rank among catch crops, which accommodates itself to all soils, requires little manure, has scarcely any exhausting effect upon the land, keeps the ground perfectly clean by the rapidity of its growth, and which, notwithstanding, yields on an average fifty-fold, and may easily be raised to double that quantity.”

—Léonce de Lavergne (1855)

Brassicas used as cover crops include mustard, rapeseed, oilseed radish, forage turnips and other species. They are increasingly used as winter or rotational cover crops in vegetable and specialty crop production, such as potatoes and tree fruits.

Rapeseed (canola is a type of rapeseed) grows well under the moist and cool conditions of late fall, when other kinds of plants are going dormant for winter. Rapeseed is killed by harsh winter conditions but is grown as a winter crop in the middle and southern sections of the United States. Both winter annual and spring-types of rapeseed and canola are available in the market.

Oilseed (forage) radish has gained a lot of interest because of its fast growth in late summer and fall, which allows significant uptake of nutrients. It develops a large taproot, 1–2 inches in diameter and a foot or more deep, that can break through compacted layers, allowing deeper rooting by the next crop (Figure 10.6). Oilseed radish will winterkill and decompose by spring, but it leaves the soil in friable condition with remnant root holes that improve rainfall infiltration and storage. It also eases root penetration and development by the following crop. All of the brassicas get much better growth as fall cover crops if planted in late summer or early fall. For winter-hardy crops, such as canola, early fall planting is critical to ensure winter survival.

Rapeseed and other brassica crops may function as biofumigants, suppressing soil pests, especially root pathogens and plant-parasitic nematodes. Row crop farmers are increasingly interested in these properties. Don’t expect brassicas to eliminate your pest problems, however. They are a good tool and an excellent rotation crop, but pest management results are inconsistent. More research is needed to further clarify the variables affecting the release and toxicity of the chemical compounds involved. Because members of this family do not develop mycorrhizal fungi associations, they will not promote mycorrhizae in the following crop.

COVER CROPS IN PERENNIAL SYSTEMS

In perennial systems like orchards and vineyards, groundcover management (floor management) can help improve soil health and crop quality. In this case, the cover crop should be a perennial with special characteristics. It should not overly compete with the main crop, and it should be persistent with minimal maintenance and provide good erosion and weed control. Also, it should be able to tolerate the conditions of the orchard floor, such as shade, traffic and drought. Basically, it functions more as a living mulch and therefore should not be too aggressive or spread laterally. A good species for this purpose is Dutch white clover, which also provides modest amounts of nitrogen. Perennial grasses like certain fescues can be attractive as a ground cover if they have a low-growing habit with dense, fine roots and require minimal mowing. Combinations of legumes and grasses may also be attractive. Sometimes, cover crops are used to deliberately compete with grapevines to reduce excessive vegetative growth, but in this situation they are kept away from the immediate vicinity of the vines.

Cover Crop Management

There are numerous management issues to consider when using cover crops. Once you decide what your major goals are for using cover crops, select one or more to try out. Consider using combinations of species. You also need to decide where cover crops best fit in your system: planted following the main crop, intercropped during part or all of the growing of the main crop, or grown for an entire growing season in order to build up the soil. The goal, while not always possible to attain, should be to have something growing in your fields (even if dormant during the winter) all the time. Other management issues include when and how to kill or suppress the cover crop, and how to reduce the possibility of interference with your main crops either by using too much water in dry climates or by becoming a weed in subsequent crops.

Mixtures of Cover Crops

Although most farmers use single species of cover crops in their fields, mixtures of different cover crops offer combined benefits. The most common mixture is a grass and legume, such as cereal rye and hairy vetch, oats and red clover, or field peas and a small grain. Other mixtures might include a legume or small grain with oilseed radishes, or even just different small grains mixed together. Mixed stands usually do a better job of suppressing weeds than a single species. Growing legumes with small grains helps compensate for the decreases in nitrogen availability for the following crop when small grains are allowed to mature. In the mid-Atlantic region, the cereal rye-hairy vetch mixture has been shown to provide another advantage for managing nitrogen: When a lot of nitrate is left in the soil at the end of the season, the rye is stimulated (reducing leaching losses). When little nitrogen is available, the vetch competes better with the rye, fixing more nitrogen for the next crop. A crop that grows erect, such as cereal rye, may provide support for hairy vetch and enable it to grow better. Mowing close to the ground kills vetch supported by rye easier than vetch alone. In no-till production systems, this may allow for mowing instead of herbicide use.

Florida farmer Ed James has found significant benefits to the health and productivity of his orange groves by using mixes of cover crops.

It helps to have a blend because if you have one species that doesn’t take, you aren’t left without any germination,” he says. “As the buckwheat begins to play out, the hairy indigo and sunn hemp start to come on. As that begins to play out, the brassicas are coming. We already have a monoculture with the trees, so the mix of cover crops makes the soil feel like it is getting a crop rotation.”

—GILES (2020)

Cover Crops and Nitrogen

Managing nitrogen supply is one of the critical challenges farmers face during a crop rotation; the aim is to have sufficient available N for the crops being grown while not having a lot of mineral N left in the soil after crop maturity, especially during seasons when it might leach out or be denitrified. Cover cropping can play an important role in N management, whether the need is to supply N for grains or vegetables, or to lower available N at the end of the season to reduce losses.

Estimating N available from cover crops. Legume cover crops can supply significant amounts of available N for the following crop. If a legume is productive and allowed to grow to the bud stage to gain sufficient size (biomass), quite a bit of N will be made available to the next crop, from 70 to well over 100 pounds per acre. But the amount of N supplied depends on the cover crop species (or mix of cover crops) and how long it’s allowed to grow. Hairy vetch and crimson clover are two of the many choices that farmers frequently turn to in order to produce a lot of N, but other legumes may prove useful as sources of N.

The amount of N that will be made available to the following crop depends on the stage of growth, the amount of growth (biomass), and the N content of the cover crop or cover crop mix. Small cover crops whose leaves are deep green, for example, in early spring, will contain a high percent of N, over 3 percent. But because there is so little mass of material, the plants contain low total amounts of N. The N percent of a cover crop such as cereal rye tends to decrease (from over 3 percent) as the plant grows more leaves and then when the stem elongates and flowering and maturity occurs, ending up well below 1 percent N with a C:N ratio of 80 or more. If the crop has a low percent N (around 1.5%–2% N), as is common with small grains when stems elongate and flowering begins, little to no N can be counted on to help the following crop because soil organisms use all the N present as they decompose the residue. (See Figure 9.3 and Table 9.4 for an explanation of the C:N ratio and its relation to percent N in residue.)

If you estimate (or measure) the mass of a cover crop at the time of termination and its percent N, you can then estimate the amount of N that may be available to the following crop by using Table 10.1.

| Table 10.1 Estimated Available N from Previous Cover Crop1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cover crop total N | Estimated available N (pounds N per acre) | |

| % N in dry matter | pounds N per ton | |

| 1 | 20 | 0 |

| 1.5 | 30 | 10 |

| 2 | 40 | 14 |

| 2.5 | 50 | 20 |

| 3 | 60 | 28 |

| 3.5 | 70 | 37 |

| 1Modified from “Estimating plant-available nitrogen release from cover crops.” PNW 636. A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication (Oregon State University, Washington State University and University of Idaho). | ||

Minimizing residual N in fall. Another way to increase N availability to the following crop is through cover crops capturing end-of-season residual N and protecting it for use by the next commercial crop. At the end of the season in some cropping systems there may be significant amounts of residual N that then can be lost through leaching below the root zone or by denitrification over the winter and early spring. This is both an economic issue for the farm and an environmental issue. Corn-soybean crop alternation and corn-corn are especially prone to high N levels in the fall and to overwinter and early spring loss. Grass cover crops such as cereal rye can help by taking up mineral N in the fall. (As mentioned above, there are good reasons to use a grass-legume mix such as cereal rye-hairy vetch in a situation where you aren’t sure whether there is or isn’t a lot of N left at the end of the season.) When there may be a lot of mineral N throughout the root zone (not just near the surface), if planted early enough, a deep-rooted cover crop such as forage radish together with cereal rye can help retain N. The forage radish can bring up nitrate from deeper in the profile in the fall, and when frost kills the radish and the nitrate leaks out, it can be taken up by cereal rye.

Planting Cover Crops

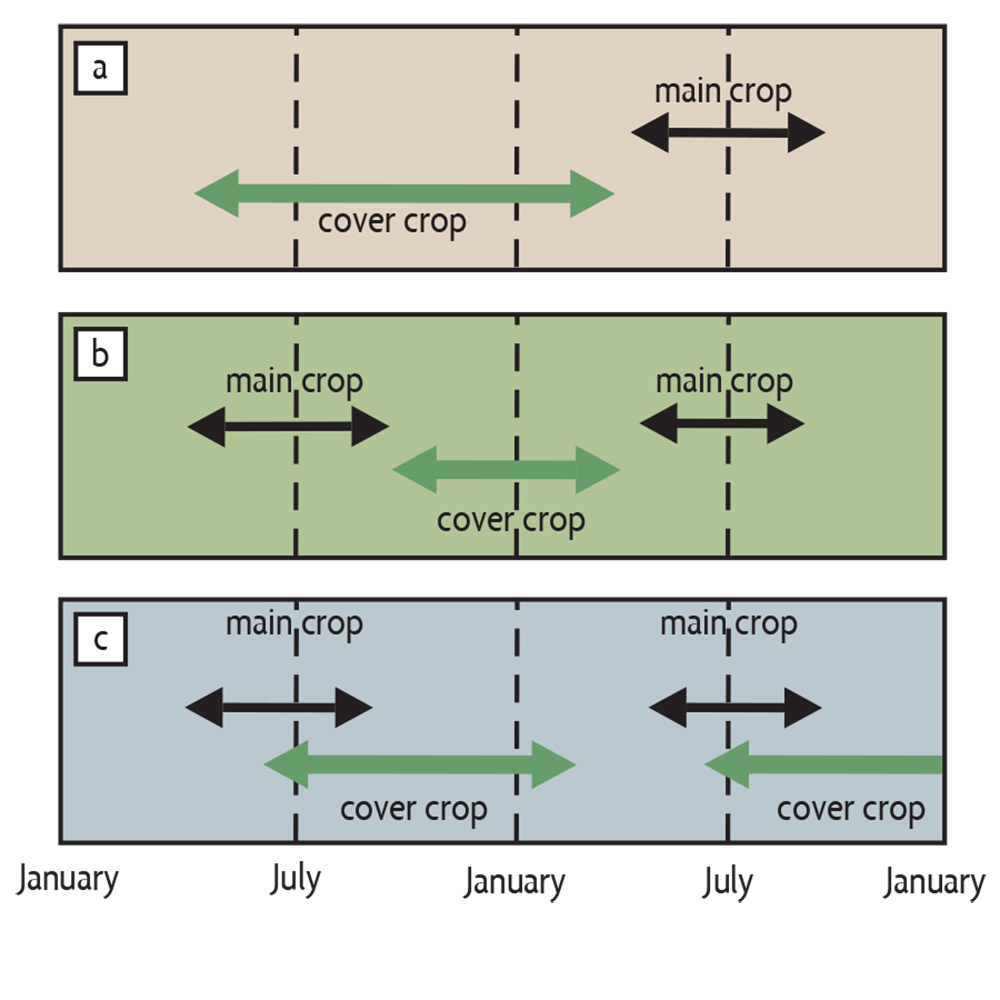

There are three ways to time the planting of a cover crop in relation to your cash crops: 1) plant a cover crop for an entire growing season; 2) plant a cover crop after the harvest of a cash crop and before planting the next cash crop; and 3) interseeding, or planting a cover crop into a growing cash crop. The approach you take will depend on your reason for planting a cover crop, your cash crops, the length of the growing season and the climate.

Planting for an entire growing season. If you want to accumulate a lot of organic matter, it’s best to grow a high-biomass mix of cover crops for the whole growing season (see Figure 10.7a), which means no income-generating crop will be grown that year. This may be especially useful with very infertile or eroded soils and when transitioning to organic farming. This is sometimes done on vegetable farms when no manure is available and in fallow systems in the western United States, but grain/oilseed farmers will not normally give up a year of production in a field.

Planting after cash crop harvest. Most farmers sow cover crops after the cash crop has been harvested (Figure 10.7b). In this case, as with the system shown in Figure 10.7a, there is no competition between the cover crop and the main crop. The seeds can be no-till planted with a grain drill or a row crop planter (no need for a high clearance interseeder) instead of broadcast, resulting in better cover crop stands. If possible, tillage should be avoided prior to cover crop seeding to maximize the soil health benefits that cover crops provide. In milder climates, you can usually plant cover crops after harvesting the main crop. In colder areas, there may not be enough time to establish a cover crop between harvest and winter. Even if you are able to get it established, there will be little growth in the fall to provide soil protection or nutrient uptake. The choice of a cover crop to fit between main summer crops (Figure 10.7b) is severely limited in northern climates by the short growing season and severe cold. Cereal rye is probably the most reliable cover crop for those conditions. In most situations, there are a range of establishment options.

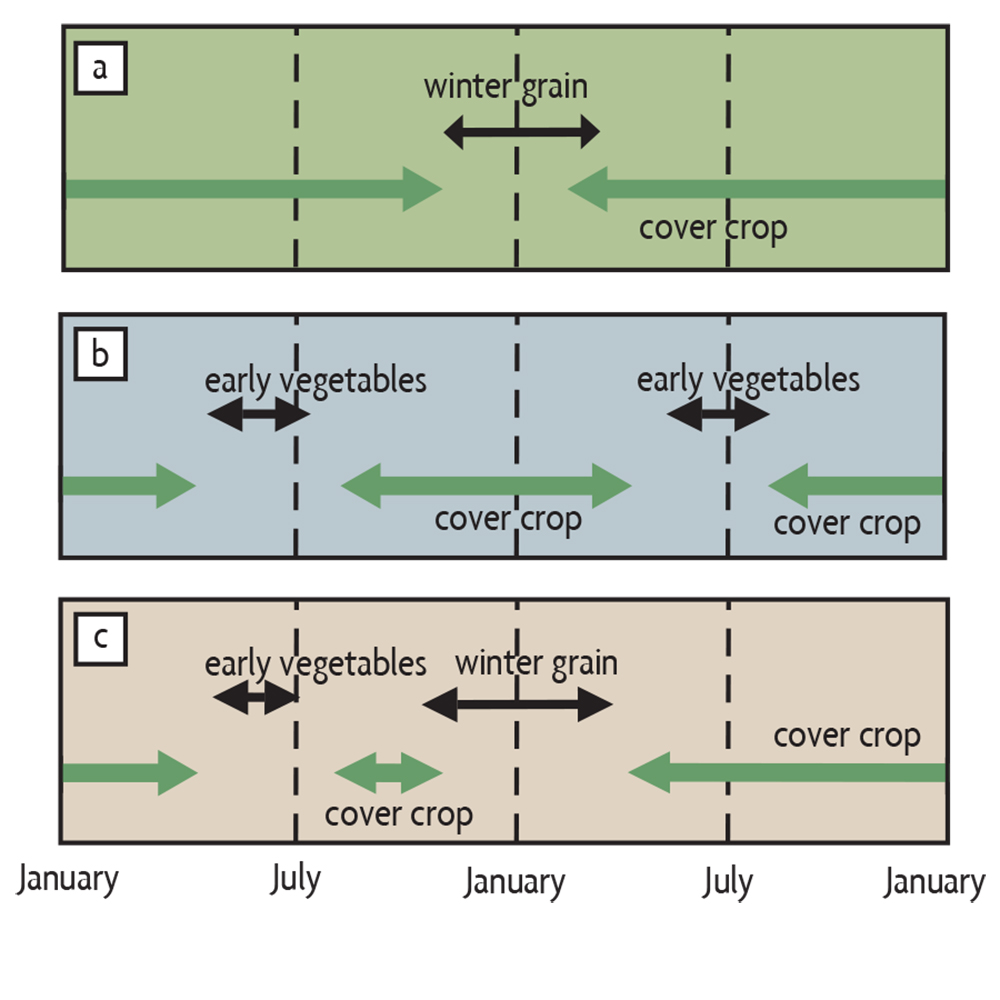

Cover crops are also established following grain harvest in late spring (Figure 10.8a). With some early maturing vegetable crops, especially in warmer regions, it is also possible to establish cover crops in early summer (Figure 10.8b). Cover crops also fit into an early vegetable-winter grain rotation sequence (Figure 10.8c).

Cover Crop Selection and Plant Parasitic Nematodes

If nematodes become a problem in your crops (common in many vegetables such as lettuce, carrots, onions and potatoes, as well as in some agronomic crops), carefully select cover crops to help limit the damage.

For example, the root-knot nematode (M. hapla) is a pest of many vegetable crops, as well as of alfalfa, soybeans and clover, but all the grain crops—corn, as well as small grains—are nonhosts. Growing grains as cover crops helps reduce nematode numbers. If the infestation is very bad, consider two full seasons with grain crops before returning to susceptible crops.

The root-lesion nematode (P. penetrans) is more of a challenge because most crops, including almost all grains, can be hosts for this organism. Whatever you do, don’t plant a legume cover crop such as hairy vetch if you have an infestation of root-lesion nematodes; it will actually stimulate nematode numbers. However, sudangrass, sorghum-sudan crosses and ryegrass, as well as pearl millet (a grain crop from Africa, grown in the United States mainly as a warm-season forage crop) have been reported to dramatically decrease nematode numbers. Some varieties appear better for this purpose than others. The suppressive activity of such cover crops is due to their poor host status to the lesion nematode, general stimulation of microbial antagonists and the release of toxic products during decomposition.

Forage-type pearl millet, sudangrass and brassicas such as mustard, rapeseed, oilseed radish and flax, all provide some biofumigation effect because when they decompose after incorporation, they produce compounds that are toxic to nematodes. Marigolds, grown sometimes as companion plants in gardens, can secrete compounds from their roots that are toxic to nematodes.

Interseeding. The third management strategy is to interseed cover crops during the growth of the main crop. Cover crops are commonly interseeded at planting in winter grain cropping systems or are frost-seeded in early spring. Seeding cover crops during the growth of cash crops (Figure 10.7c) is especially helpful for the establishment of cover crops in areas with a short growing season. Delaying the cover crop seeding until the main crop is off to a good start means that the commercial crop will be able to grow well despite the competition. Good establishment of cover crops requires moisture and, for small-seeded crops, some covering of the seed by soil or crop residues. High clearance grain drills can be used to obtain good seed-to-soil contact when interseeding a cover crop (Figure 10.9). Cereal rye is able to establish well without seed covering, as long as sufficient moisture is present. Farmers using this system will broadcast seed during or just after the last cultivation of a row crop. Aerial seeding, “highboy” tractors, or detasseling machines are used to broadcast green manure seed after a main crop is already fairly tall, like with corn. When growing is on a smaller scale, seed is broadcast with the use of a hand-crank spin seeder. This works best for some of the grasses, and its success depends on the soil surface being moist for germination and establishment to occur.

Intercrops and living mulches. Growing a cover crop between the rows of a main crop has been practiced for a long time. It has been called a living mulch or an orchard-floor cover, with the cover crop established before the main crop. Intercropping, with the cover crop established at or soon after planting, has many benefits. Compared with bare soil, a ground cover provides erosion control, better conditions for using equipment during harvest, higher water-infiltration capacity, and an increase in soil organic matter. In addition, if the cover crop is a legume, a significant buildup of nitrogen may be available to crops in future years. Another benefit is the attraction of beneficial insects, such as predatory mites, to flowering plants. Less insect damage has been noted under polyculture than under monoculture.

Growing other plants near the main crop also poses potential dangers. The intercrop may harbor insect pests, such as the tarnished plant bug. Most of the management decisions for using intercrops are connected with minimizing competition with the main crop. Intercrops, if they grow too tall, can compete with the main crop for light, or may physically interfere with the main crop’s growth or harvest. Intercrops may compete for water and nutrients. Using intercrops is not recommended if rainfall is barely adequate for the main crop and supplemental irrigation isn’t available. Soil-improving intercrops established by delayed planting into annual main crops are usually referred to as interseeded cover crops. Herbicides, mowing and partial rototilling are used to suppress the cover crop and give an advantage to the main crop. Another way to lessen competition from the cover is to plant the main crop in a relatively wide cover-free strip (Figure 10.10). This provides more distance between the main crop and the intercrop rows. When establishing orchards and vineyards, one way to reduce competition is to plant the living mulch after the main perennial crops are well established.

"Planting Green" Into Cover Crops

In the past, the recommendation was to leave a week or two between the time the cover crop was killed and when the cash crop was planted. That is still the best approach in certain situations, such as in a dry spring. In fact, in a dry spring, terminating a few weeks ahead of the cash crop may be needed.

However, more and more farmers are now "planting green," where the cash crop is directly seeded into a still living cover crop. (In a 2019–2020 national survey, 54% of farmers reported that they plant green. See the box “Farmers Say Cover Crops Help the Bottom Line.”) Most often, the cover crop is sprayed with an herbicide shortly after the cash crop is planted.

Mechanical control of the cover crop is another option. For example, good suppression of hairy vetch in a no-till system has been obtained with the use of a modified rolling stalk chopper at early bloom. Farmers are also experiencing good cover crop suppression using cereal rye and a roller-crimper that goes ahead of the tractor, allowing the possibility of no-till planting a main crop at the same time as suppressing the cover crop (see Figure 16.10). Although not recommended for most direct-seeded vegetable crops, this has been successfully used for soybeans, corn and cotton.

Cover Crop Termination

No matter when you establish cover crops, they are usually killed or drastically weakened before or during soil preparation for the next cash crop. This preparation is usually done by one of the following approaches: mowing once they’ve flowered (most annuals can be killed that way), using herbicides and no-till, plowing into the soil (with or without use of herbicides), or mowing, rolling and crimping and no-till planting in the same operation, or naturally by winter injury. In some cases it is a good idea to leave a week or two between the time a cover crop is tilled in or killed and the time a main crop is planted. Studies have found that a sudex cover crop is especially allelopathic and that tomatoes, broccoli and lettuce should not be planted until six to eight weeks to allow for thorough leaching of residue. This allows some decomposition to occur and may lessen problems of nitrogen immobilization and allelopathic effects, as well as avoiding increased seed decay and damping-off diseases (especially under wet conditions) and problems with cutworm and wireworm. It also may allow for the establishment of a better seedbed for small-seeded crops, such as some of the vegetables. Establishing a good seedbed for crops with small seeds may be difficult because of the lumpiness caused by the fresh residues.

Cover crops can also be terminated by partially or wholly harvesting the biomass. You might argue that cover crops should be grown for the purpose of improving the soil, not to be harvested or grazed. But sometimes farmers use a hybrid or adaptive system, especially if they have livestock. For example, if a cereal rye crop comes up quickly after the winter in a warm spring, a farmer might decide to harvest the extra biomass for hay or haylage. In other cases it might be worthwhile to allow animals to graze the cover crop, which still cycles much of the carbon and nutrients (see Chapter 12). Even though much of the aboveground biomass is harvested, the soil still benefits from the root biomass and, in the case of grazing, from the manure.

Management Cautions

Cover crops can cause serious problems if not managed carefully. They can deplete soil moisture; they can become weeds; and, when used as an intercrop, they can compete with the cash crop for water, light and nutrients. They also tend to be somewhat costly in terms of seed and establishment, so you want to ensure that the benefits pay off.

In drier areas and on droughty soils, such as sands, late killing of a winter cover crop may result in moisture deficiency for the main summer crop. In that situation, the cover crop should be killed before too much water is removed from the soil. However, in warm, humid climates where no-till methods are practiced, allowing the cover crop to grow longer means fewer problems with soil being very wet or saturated at planting, and more residue and water conservation for the main crop later in the season. Cover crop mulch may more than compensate for the extra water removed from the soil during the later period of green manure growth.

Greater formation of large (macro) pores with cover crops leads to more rainfall infiltration, while higher organic matter levels following their use leads to greater soil waterholding capacity. Surface residue also slows runoff of rainfall, which allows more to infiltrate into the soil. In addition, greater mycorrhizal fungi presence following cover crops may aid water uptake, and cover crops may lead to cash crops rooting deeper and reaching more water. Considering all their effects, cover crops normally greatly enhance the water status of soils for cash crops. In addition, in very humid regions or on wet soils, the ability of an actively growing cover crop to “pump” water out of the soil by transpiration may be an advantage (see Figure 15.8). Letting the cover crop grow as long as possible results in more rapid soil drying and allows for earlier planting of the main crop.

Using bin-run cover crop seed that hasn't been properly cleaned can result in introducing weed seeds into fields. And on rare occasions cover crops may become unwanted weeds in succeeding crops. Cover crops are sometimes allowed to flower to provide pollen to bees or other beneficial insects. However, if the plants actually set seed, the cover crop may reseed unintentionally. On organic farms the hard seed of vetch allows it to become a pest in small grains such as wheat. Cover crops that may become a weed problem include buckwheat, ryegrass and hairy vetch, but there is usually no concern with timely termination. On the other hand, natural reseeding of subclover, crimson clover or velvet beans might be beneficial in some situations.

Another issue to consider is that a cover crop might harbor a disease of crop plants and form a habitat bridge from one growing season to another. For example, oilseed radishes increase clubroot in broccoli. Finally, thick-mulched cover crops make good habitat for soil organisms and also for some undesirable species. Animals like rats, mice and snakes (in warm climates) may be found under the mulch, which might affect yields and crop quality, and caution is recommended when manual fieldwork is performed.

A Case Study, Gabe Brown

Bismarck, North Dakota

It’s fair to say that Gabe Brown didn’t see change coming when he and his wife Shelly purchased their now-5,000-acre ranch from Shelly’s parents upon their retirement in 1991. The ranch, which had been operated by Brown’s in-laws, produced monocultures of small grains and relied on conventional production methods, including frequent tillage, fertilization, season-long grazing and chemical treatments. As Brown himself had been taught those production models for most of his life, he continued to work the ranch as it had been run for decades.

But 1995 and 1996 brought devastating hailstorms that destroyed his crops, and a drought in 1997 decimated that year’s crop. As if that wasn’t punishment enough, another hailstorm followed in 1998, destroying his crops once again. If the ranch was going to survive, things needed to change, and the land needed to recover. Bismarck is not an easy place to farm—the temperature can drop below freezing more than 220 days a year and annual rainfall averages around 16 inches, most of which falls during May and June thunderstorms. These extremes make severe weather events even more hazardous, and Brown was experiencing that firsthand.

At risk of losing his ranch, Brown was suddenly thrust into the position where he had to change his practices in order to save his business. He had heard about and learned of the successes of other farmers who chose a soil-first strategy for their operations. Those regenerative agriculture practices focused on reducing or eliminating tillage, ending the habitual use of synthetic chemicals for pest management and fertilization, and planting cover crops to reduce erosion and to capture nutrients in the soil. Though there was no way to control the climate or to stop extreme weather events, shifting to holistic management could make the property more resilient by strengthening the soil to protect it from wind and water, improving water infiltration and waterholding capacities to reduce drought risks, and shielding the land from temperature extremes by keeping it covered with either a living cover crop or crop residues. If he could rehabilitate the soil and bring it back to life by treating his land as a living organism, it was likely his business would not only survive but would also thrive.

Committed to saving his land and bringing the ranch back to life, Brown made a choice. Step by step, he experimented with and integrated regenerative, holistic production methods into the operation of Brown’s Ranch, which now produces a variety of cash crops, cover crops, and grass-finished beef and lamb, as well as pastured laying hens, broilers and pork. “We haven’t used synthetic fertilizers since 2008, and we use no fungicides or other pesticides,” notes Brown. As a result of shifting to regenerative agriculture practices, the no-till ranch has seen immense improvements in all aspects of the operation, including reduced erosion, improved yields, increased soil organic matter, several new inches of topsoil and increased profitability.

During the transition, Brown fully committed to using a diverse mix of cover crops, which have increased his soil organic matter, reduced weed pressure, promoted beneficials, improved waterholding capacity and improved infiltration by breaking up soil compaction. His cover crop mixes include up to 25 different species. “Our goal is to have a living root in the soil as long as possible,” Brown states. Every acre of his cropland has “either a cover crop growing before the cash crop, after the cash crop, or with the cash crop.” Cover crop residue then helps to maintain desired soil temperature and to feed beneficial organisms.

Soil organic matter levels were 1.7–1.9% when he purchased the operation, and the precipitation infiltration rate was a scant half an inch per hour. But after more than 20 years of cover cropping, livestock integration and diverse crop rotations, Brown’s Ranch has soil organic matter levels that hover around 5.3–7.9%, and the infiltration rate has skyrocketed to more than 30 inches of rainfall per hour, which means that precipitation always enters the soil and runoff never occurs.

Livestock are thoroughly integrated throughout his ranch, including on the 2,000 acres of cropland. Brown believes grazing livestock plays a critical role in improving soil health. The integration of livestock into the cropping system results in deposits of dung and urine on the land. Those deposits are consumed by macro- and microorganisms that provide nutrients to the living crops and subsequent covers.

When there is a nutrition and forage need that arises during the season, Brown relies on his cover cropping plan to fill that gap. Fall-season biennials like winter triticale and hairy vetch meet nutrient requirements for calving while also providing “armor” for the soil. Soil sample data shows that grazed fields with a diverse cover crop mix have increased availability of all nutrients, thus adding to profitability.

Brown’s increased crop yields and financial savings have shown to be quite impressive: “We have a 127-bushel-proven dryland corn yield, while the county average is under 100. So we’re over 25% higher than county average, without many of the costs involved. We’re saving a tremendous amount on inputs.” Brown’s Ranch relies on its healthy soil to provide the necessary nutrients for its crops: The diverse cover crop mix feeds soil organisms, which in turn provide necessary nutrients for crop growth.

Pasture management at Brown’s Ranch is guided by the principles of getting adequate organic residue into contact with the soil through animal impact and then allowing forages plenty of time to recover from grazing. This means Brown’s rotational grazing strategy is very intensive: Stocking rates are high and rotations are frequent. Permanent pastures are 15–40 acres in size and are divided further with portable fencing into paddocks one sixth of an acre to 5 acres. The 300-pair cowherd is typically moved once a day, and 200–600 yearlings are moved 1–5 times a day. While this seems like a lot of work, solar-powered gate openers that operate on a timer allow the animals to move themselves.

In this system, cattle will usually consume 30–40% of the aboveground biomass in a particular paddock and will trample most of the remaining sward. Most paddocks receive at least 360 days of recovery before they’re grazed again. The ranch has its own marketing label for its grass-finished beef, lamb, pastured pork, eggs, broilers and honey.Gabe Brown is a soil health convert. When he’s not on the farm working with his son Paul, he is speaking at events and conferences, giving farm tours or teaching at a Soil Health Academy school. His 2018 book Dirt to Soil: One Family’s Journey into Regenerative Agriculture shares the tale of the evolution of Brown’s Ranch and offers solutions to many soil-health difficulties experienced by farmers and ranchers across the United States. By choosing to focus on the health of his living land, and by not being afraid to fail a little along the way, Brown has transformed his business and has made his operation more resilient to any challenges the future may hold.

Chapter 10 Sources

Abawi, G.S. and T.L. Widmer. 2000. Impact of soil health management practices on soilborne pathogens, nematodes and root diseases of vegetable crops. Applied Soil Ecology 15: 37–47.

Allison, F.E. 1973. Soil Organic Matter and Its Role in Crop Production. Elsevier Scientific Publishing: Amsterdam. In his discussion of organic matter replenishment and green manures (pp. 450–451), Allison cites a number of researchers who indicate that there is little or no effect of green manures on total organic matter, even though the supply of active (rapidly decomposing) organic matter increases.

Björkman, T., R. Bellinder, R. Hahn and J. Shail, Jr. 2008. Buckwheat Cover Crop Handbook. Cornell University: Geneva, NY. http://www.nysaes.cornell.edu/hort/faculty/bjorkman/covercrops/pdfs/bwbrochure.pdf.

Clark, A., ed. 2007. Managing Cover Crops Profitably, 3rd ed. Handbook Series, No. 9. USDA-SARE: College Park, MD. www.sare.org. An excellent source for practical information about cover crops.

Cornell University. Cover Crops for Vegetable Growers. http:// www.nysaes.cornell.edu/hort/faculty/bjorkman/covercrops/why.html.

Giles, F. 2020. Soil Health Matters! A Tale of 2 Florida Citrus Groves. Growing Produce (Feb. 3, 2020). www.growingproduce.com/citrus/soil-health-matters-a-tale-of-2-florida-citrus-groves/

Hargrove, W.L., ed. 1991. Cover Crops for Clean Water. Soil and Water Conservation Society: Ankeny, IA.

MacRae, R.J. and G.R. Mehuys. 1985. The effect of green manuring on the physical properties of temperate-area soils. Advances in Soil Science 3: 71–94.

McDaniel, M.D., Tiemann, L.K. and Grandy, A.S., 2014. Does agricultural crop diversity enhance soil microbial biomass and organic matter dynamics? A meta‐analysis. Ecological Applications, 24(3), pp.560–570.

Miller, P.R., W.L. Graves, W.A. Williams and B.A. Madson. 1989. Cover Crops for California Agriculture. Leaflet 21471. University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources: Davis, CA. This is the reference for the experiment with clover in California.

Myers, R.L., J.A. Weber and S.R. Tellatin. 2019. Cover Crop Economics. Technical Bulletin. USDA-SARE: College Park, MD. 24 p.

Nunes, M., R.R. Schindelbeck, H.M. van Es, A. Ristow and M. Ryan. 2018. Soil Health and Maize Yield Analysis Detects Long-Term Tillage and Cropping Effects. Geoderma 328: 30–43.

Pieters, A.J. 1927. Green Manuring Principles and Practices. John Wiley: New York, NY.

Power, J.F., ed. 1987. The Role of Legumes in Conservation Tillage Systems. Soil Conservation Society of America: Ankeny, IA.

Sarrantonio, M. 1997. Northeast Cover Crop Handbook. Soil Health Series. Rodale Institute: Kutztown, PA.

Smith, M.S., W.W. Frye and J.J. Varco. 1987. Legume winter cover crops. Advances in Soil Science 7: 95–139.

Sogbedji, J.M., H.M. van Es and K.M. Agbeko. 2006. Cover cropping and nutrient management strategies for maize production in western Africa. Agronomy Journal 98: 883–889.

Sullivan, D.M. and N.D. Andrews. 2012. Estimating plant-available nitrogen release from cover crops. PNW 636. A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication (Oregon State University, Washington State University and University of Idaho).

Summers, C.G., J.P. Mitchell, T.S. Prather and J.J. Stapleton. Sudex cover crops can kill and stunt subsequent tomato, lettuce, and broccoli transplants through allelopathy. California Agriculture 63(2): 35–40.

Weil, R. and A. Kremen. 2007. Thinking across and beyond disciplines to make cover crops pay. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 87: 551–557.

Widmer, T.L. and G.S. Abawi. 2000. Mechanism of suppression of Meloidogyne hapla and its damage by a green manure of sudan grass. Plant Disease 84: 562–568.

White, C., M. Barbercheck, T. DuPont, D. Finney, A. Hamilton, D, Hartman, M. Hautau, J. Hinds, M. Hunter, J. Kaye and James LaChance. 2015. Making the Most of Mixtures: Considerations for Winter Cover Crops in Temperate Climates, The Pennsylvania State University. https://extension.psu.edu/making-the-most-of-mixtures-considerations-for-winter-cover-crops.