Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum)

Type: winter annual cereal grain; can be spring-planted

Roles: prevent erosion, suppress weeds, scavenge excess nutrients, add organic matter

Mix with: annual legumes, ryegrass or other small grains

See charts, pp. 66 to 72, for ranking and management summary.

Although typically grown as a cash grain, winter wheat can provide most of the cover crop benefits of other cereal crops, as well as a grazing option prior to spring tiller elongation. It’s less likely than barley or rye to become a weed and is easier to kill. Wheat also is slower to mature than some cereals, so there is no rush to kill it early in spring and risk compacting soil in wet conditions. It is increasingly grown instead of rye because it is cheaper and easier to manage in spring.

Whether grown as a cover crop or for grain, winter wheat adds rotation options for underseeding a legume (such as red clover or sweet-clover) for forage or nitrogen. It works well in no-till or reduced-tillage systems, and for weed control in potatoes grown with irrigation in semiarid regions.

Benefits of Winter Wheat Cover Crops

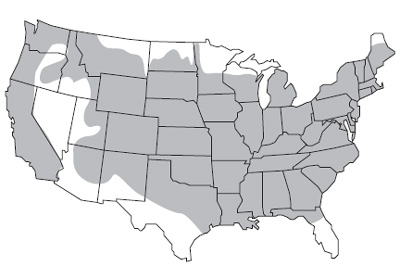

Erosion control. Winter wheat can serve as an overwintering cover crop for erosion control in most of the continental U.S.

Nutrient catch crop. Wheat enhances cycling of N, P and K. A heavy N feeder in spring, wheat takes up N relatively slowly in autumn. It adds up, however. A September-seeded stand absorbed 40 lb. N/A by December, a Maryland study showed (46). As an overwintering cover rather than a grain crop, wheat wouldn’t need fall or spring fertilizer.

A 50 bushel wheat crop can take up 20 to 25 lb. P2O5 and 60 lb. K2O per acre by boot stage. About 80 percent of the K is recycled if the stems and leaves aren’t removed from the field at harvest. All the nutrients are recycled when wheat is managed as a cover crop, giving it a role in scavenging excess nitrogen.

“Cash and Cover” crop. Winter wheat can be grown as a cash crop or a cover crop, although you should manage each differently. It provides a cash-grain option while also opening a spot for a winter annual legume in a corn>soybean or similar rotation. For example:

- In the Cotton Belt, wheat and crimson clover would be a good mix.

- In Hardiness Zone 6 and parts of Zone 7, plant hairy vetch after wheat harvest, giving the legume plenty of time to establish in fall. Vetch growth in spring may provide most of the N necessary for heavy feeders such as corn, or all of the N for sorghum, in areas northward to southern Illinois, where early spring warm-up allows time for development.

- In much of Zone 7, cowpeas would be a good choice after wheat harvest in early July or before planting winter wheat in fall.

- In the Corn Belt and northern U.S., undersow red clover or frostseed sweetclover into a wheat nurse crop if you want the option of a year of hay before going back to corn. With or without underseeding a legume or legume-grass mix, winter wheat provides great grazing and nutritional value and can extend the grazing season.

- In Colorado vegetable systems, wheat reduced wind erosion and scavenged N from 5 feet deep in the profile (111, 114).

- In parts of Zone 6 and warmer, you also have a dependable double-crop option. See Wheat Boosts Income and Soil Protection.

Weed suppressor. As a fall-sown cereal, wheat competes well with most weeds once it is established (71). Its rapid spring growth also helps choke weeds, especially with an underseeded legume competing for light and surface nutrients.

Soil builder and organic matter source. Wheat is a plentiful source of straw and stubble. Wheat’s fine root system also improves topsoil tilth. Although it generally produces less than rye or barley, the residue can be easier to manage and incorporate.

When selecting a locally adapted variety for use as a cover crop, you might not need premium seed. A Maryland study of 25 wheat cultivars showed no major differences in overall biomass production at maturity (92). Also in Maryland, wheat produced up to 12,500 lb. biomass/A following high rates of broiler litter (87).

In Colorado, wheat planted in August after early vegetables produced more than 4,000 lb. biomass/A, but if planted in October, yielded only one-tenth as much biomass and consequently scavenged less N (114).

If weed control is important in your system, look for a regional cultivar that can produce early spring growth. To scavenge N, select a variety with good fall growth before winter dormancy.

Wheat Boosts Income and Soil Protection

Wheat is an ideal fall cover crop that you can later decide to harvest as a cash crop, cotton farmer Max Carter has found. “It’s easier to manage than rye, still leaves plenty of residue to keep topsoil from washing away—and is an excellent double crop,” says Carter.

The southeastern Georgia farmer no-till drills winter wheat at 2 bushels per acre right after cotton harvest, without any seedbed preparation. “It gives a good, thick stand,” he says.

“We usually get wheat in by Thanksgiving, but as long as it’s planted by Christmas, I know it’ll do fine,” he adds. After drilling wheat, Carter goes back and mows the cotton stalks to leave some field residue until the wheat establishes.

Disease or pests rarely have been a problem, he notes.

“It’s a very easy system, with wheat always serving as a fall cover crop for us. It builds soil and encourages helpful soil microorganisms. It can be grazed, or we can burn some down in March for planting early corn or peanuts anytime from March to June,” he says.

For a double crop before 2-bale-an-acre cotton, Carter irrigates the stand once in spring with a center pivot and harvests 45- to 60-bushel wheat by the end of May. “The chopper on the rear of the combine puts the straw right back on the soil as an even blanket and we’re back planting cotton on June 1.”

“It sure beats idling land and losing topsoil.”

Management of Winter Wheat Cover Crops

Establishment & Fieldwork for Winter Wheat Cover Crops

Wheat prefers well-drained soils of medium texture and moderate fertility. It tolerates poorly drained, heavier soils better than barley or oats, but flooding can easily drown a wheat stand. Rye may be a better choice for some poor soils.

Biomass production and N uptake are fairly slow in autumn. Tillering resumes in late winter/ early spring and N uptake increases quickly during stem extension.

Adequate but not excessive N is important during wheat’s early growth stages (prior to stem growth) to ensure adequate tillering and root growth prior to winter dormancy. In low-fertility or light-textured soils, consider a mixed seeding with a legume (80). See Wheat Offers High Value Weed Control, Too.

A firm seedbed helps reduce winterkill of wheat. Minimize tillage in semiarid regions to avoid pulverizing topsoil (358) and depleting soil moisture.

Winter annual use. Seed from late summer to early fall in Zone 3 to 7— a few weeks earlier than a rye or wheat grain crop—and from fall to early winter in Zone 8 and warmer. If you are considering harvesting as a grain crop, you should wait until the Hessian fly-free date, however. If cover crop planting is delayed, consider sowing rye instead.

Drill 60 to 120 lb./A (1 to 2 bushels) into a firm seedbed at a 1/2- to 11/2-inch depth or broadcast 60 to 160 lb./A (1 to 2.5 bushels) and disk lightly or cultipack to cover. Plant at a high rate if seeding late, when overseeding into soybeans at the leafyellowing stage, when planting into a dry seedbed or when you require a thick, weed-suppressing stand. Seed at a low to medium rate when soil moisture is plentiful (71).

After cotton harvest in Zone 8 and warmer, no-till drill 2 bushels of wheat per acre without any seedbed preparation. In the Southern Plains, 1 bushel is sufficient if drilling in a timely fashion (302).

With irrigation or in humid regions, you could harvest 45- to 60-bushel wheat, then double crop with soybeans, cotton or another summer crop. See Wheat Boosts Income and Soil Protection. You also could overseed winter wheat prior to cotton defoliation and harvesting.

Another possibility for Zone 7 and cooler: Plant full-season soybeans into wheat cover crop residue, and plant a wheat cover crop after bean harvest.

Winter Wheat Cover Crops Offers High-Value Weed Control

Pairing a winter wheat cover crop with a reduced herbicide program in the inland Pacific Northwest could provide excellent weed control in potatoes grown on light soils in irrigated, semiarid regions. A SARE-funded study showed that winter wheat provided effective competition against annual weeds that infest irrigated potato fields in Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

Banding herbicide over the row when planting potatoes improved the system’s effectiveness, subsequent research shows, says project coordinator Dr. Charlotte Eberlein at the University of Idaho’s Aberdeen Research and Extension Center. “In our initial study, we were effectively no-tilling potatoes into the Roundup-killed wheat,” says Eberlein. In this study we killed the cover crop and planted potatoes with a regular potato planter, which rips the wheat out of the potato row, a grower then can band a herbicide mixture over the row and depend on the wheat mulch to control between-row weeds.

“If you have sandy soil to start with and can kill winter wheat early enough to reduce water-management concerns for the potatoes, the system works well,” says Eberlein.

“Winter rye would be a slightly better cover crop for suppressing weeds in a system like this,” she notes. “Volunteer rye, however, is a serious problem in wheat grown in the West, and wheat is a common rotation crop for potato growers in the Pacific Northwest.”

She recommends drilling winter wheat at 90 lb./A into a good seedbed, generally in mid- September in Idaho. “In our area, growers can deep rip in fall, disk and build the beds (hills), then drill wheat directly into the beds,” she says. Some starter N (50 to 60 lb./A) can help the wheat establish. If indicated by soil testing, P or K also would be fall-applied for the following potato crop.

The wheat usually does well and shows good winter survival. Amount of spring rainfall and soil moisture and the wheat growth rate determine the optimal dates for killing wheat and planting potatoes.

Some years, you might plant into the wheat and broadcast Roundup about a week later. Other years, if a wet spring delays potato planting, you could kill wheat before it gets out of hand (before the boot stage), then wait for better potato-planting conditions.

Moisture management is important, especially during dry springs, she says. “We usually kill the wheat from early to mid May— a week or two after planting potatoes. That’s soon enough to maintain adequate moisture in the hills for potatoes to sprout.”

An irrigation option ensures adequate soil moisture—for the wheat stand in fall or the potato crop in spring, she adds. “You want a good, competitive wheat stand and a vigorous potato crop if you’re depending on a banded herbicide mix and wheat mulch for weed control,” says Eberlein. That combination gives competitive yields, she observes, based on research station trials.

Mixed seeding or nurse crop. Winter wheat works well in mixtures with other small grains or with legumes such as hairy vetch. It is an excellent nurse crop for frostseeding red clover or sweetclover, if rainfall is sufficient. In the Corn Belt, the legume is usually sown in winter, before wheat’s vegetative growth resumes. If frostseeding, use the full seeding rates for both species, according to recent work in Iowa (34). If you sow sweetclover in fall with winter wheat, it could outgrow the wheat. If you want a grain option, that could make harvest difficult.

Spring annual use. Although it’s not a common practice, winter wheat can be planted in the spring as a weed-suppressing companion crop or early forage. You sacrifice fall nutrient scavenging, however. Reasons for spring planting include winter kill or spotty overwintering, or when you just didn’t have time to fall-seed it. It won’t have a chance to vernalize (be exposed to extended cold after germination), so it will not head out and usually dies on its own within a few months, without setting seed. This eliminates the possibility of it becoming a weed problem in subsequent crops. By sowing when field conditions permit in early spring, within a couple months you could have a 6- to 10-inch tall cover crop into which you can no-till your cash crop. You might not need a burndown herbicide, either.

Early spring planting of spring wheat, with or without a legume companion, is an option, especially if you have a longer rotation niche available.

Field Management for Winter Wheat Cover Crops

You needn’t spring fertilize a winter wheat stand being grown as a cover crop rather than a grain crop. That would defeat the primary purpose (N scavenging) of growing a small grain cover crop. As with any overwintering small grain crop, however, you will want to ensure the wheat stand doesn’t adversely affect soil moisture or nutrient availability for the following crop.

Killing of Winter Wheat Cover Crops

Kill wheat with a roller crimper at soft-dough stage or later, with a grass herbicide, or by plowing, disking or mowing before seed matures. As with other small grain cover crops, it is safest to kill about 2-3 weeks before planting your cash crop, although this will depend on local conditions and your killing and tillage system.

Because of its slower spring growth, there is less need to rush to kill wheat in spring as is sometimes required for rye. That’s one reason vegetable grower Will Stevens of Shoreham, Vt., prefers wheat to rye as a winter cover on his heavy, clay-loam soils. The wheat goes to seed slower and can provide more biomass than an earlier killing of rye would, he’s found. With rye, he has to disk two to three weeks earlier in spring to incorporate the biomass, which can be a problem in wet conditions. “I only chisel plow wheat if it’s really rank,” he notes.

Pest Management for Winter Wheat Cover Crops

Wheat is less likely than rye or barley to become a weed problem in a rotation, but is a little more susceptible than rye or oats to insects and disease. Managed as a cover crop, wheat rarely poses an insect or disease risk. Diseases can be more of a problem the earlier wheat is planted in fall, especially if you farm in a humid area.

Growing winter wheat could influence the buildup of pathogens and affect future small-grain cash crops, however. Use of resistant varieties and other IPM practices can avoid many pest problems in wheat grown for grain. If wheat diseases or pests are a major concern in your area, rye or barley might be a better choice as an overwintering cover crop that provides a grain option, despite their lower grain yield.

Other Options with Winter Wheat Cover Crops

Choosing wheat as a small-grain cover crop offers the flexibility in late spring or early summer to harvest a grain crop. Spring management such as removing grazing livestock prior to heading and topdressing with N is essential for the grain crop option.