… the popular mind is still fixed on the idea that a fertilizer is the panacea.

—J.L. Hills, C.H, Jones and C. Cutler, 1908

Although fertilizers and other amendments purchased from off the farm are not a panacea to cure all soil problems, they play an important role in maintaining soil productivity. Soil testing is the farmer’s best means for determining which amendments or fertilizers are needed and how much should be used.

The soil test report provides the soil’s nutrient and pH levels, organic matter content, cation exchange capacity (CEC) and, in arid climates, the salt and sodium levels. Recommendations for application of nutrients and amendments accompany most reports. They are based on soil nutrient levels, past cropping and manure management, and should be a customized recommendation based on the crop you plan to grow.

Soil tests, and proper interpretation of results, are an important tool for developing a farm nutrient management program. However, deciding how much fertilizer to apply—or the total amount of nutrients needed from various sources—is part science, part philosophy and part art. Understanding soil tests and how to interpret them can help farmers better customize the test’s recommendations. In this chapter, we’ll go over sources of confusion about soil tests; discuss N, P, other nutrients and organic matter soil tests; and then examine a number of sample soil tests to see how the information they provide can help you make decisions about fertilizer application.

Taking Soil Samples

The usual time to take soil samples for general fertility evaluation is in the fall or the spring, before the growing season has begun. These samples are analyzed for pH and lime requirements as well as for phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium. Some labs also routinely analyze for organic matter and other selected nutrients, such as boron, zinc, sulfur and manganese, while others offer these as part of a menu you can select from. Whether you sample a particular field in the fall or in the early spring, stay consistent and repeat samples at approximately the same time of the year and use the same laboratory for analysis. Keep in mind that soils are usually sampled differently (timing and depth) for evaluating N needs (see below). As you will see below, this allows you to make better year-to-year comparisons.

GUIDELINES FOR TAKING SOIL SAMPLES

- Care and consistency when taking samples are critical to obtaining accurate information. Plan when and how you are going to sample, and be sure there is sufficient time to do it correctly.

- Don’t wait until the last minute. The best time to sample for a general soil test is usually in the fall. Spring samples should be taken early enough to have the results in time to properly plan nutrient management for the crop season.

- Take cores from at least 15–20 spots randomly selected over the field (or a zone in a field) to obtain a representative sample. Taking many cores for a single sample is critical for obtaining meaningful soil test results, independent of the size of the field or zone. One sample should not represent more than 10–20 acres. For precision zone or grid fertility management, consider a sample for every 1–5 acres.

- Sample between rows. Avoid old fence rows, dead furrows and other spots that are not representative of the whole field.

- Take separate samples from problem areas if they can be treated separately.

- Soils are not homogeneous: nutrient levels can vary widely with different crop histories or topographic settings. Sometimes different colors are a clue to different nutrient contents. Consider sampling some areas separately, even if yields are not noticeably different from the rest of the field.

- For diversified vegetable farms that use blocks for grouping crops (by plant family, periods of growth, type of crop), sample by management zone block in addition to visibly different portions of fields, like strips or other portions of fields that form the basis of the rotation.

- In cultivated fields, sample to plow depth.

- Take two samples from no-till fields: one to a 6-inch depth for lime and fertilizer recommendations, and one to a 2-inch depth to monitor surface acidity.

- Sample permanent pastures to a 3- or 4-inch depth.

- Collect the samples in a clean container.

- Mix the core samplings, remove roots and stones, and allow the mixed sample to air dry.

- Fill the soil-test mailing container.

- Complete the information sheet, giving all of the information requested. Remember, the recommendations are only as good as the information supplied.

- Sample fields at least every three years and at the same season of the year each time. Annual soil tests on higher-value crops will allow you to fine-tune nutrient management and may allow you to cut down on fertilizer use.

—Modified from The Penn State Agronomy Guide (2019–2020)

Accuracy of Recommendations Based on Soil Tests

Soil tests and their recommendations, although a critical component of fertility management, are not 100% accurate. Soil tests are an important tool, but they need to be used by farmers and farm advisors along with other information to make the best decision regarding amounts of fertilizers or amendments to apply.

Soil tests are an estimate of a limited number of plant nutrients based on a small sample, which is supposed to represent many acres in a field. With soil testing, the answers aren’t as certain as we might like them to be. A soil test that reveals a low level of a particular nutrient suggests that you will probably increase yield by adding the nutrient. However, adding it may not always increase crop yields. This could happen if the soil test is not well calibrated for the particular soil in question (and because the soil had sufficient availability of the nutrient for the crop despite the low test level) or because of harm caused by poor drainage or compaction. Occasionally, using extra nutrients on a high-testing soil increases crop yields. Weather conditions may have made the nutrient less available than indicated by the soil test. So it’s important to use common sense when interpreting soil test results.

ASKING THE PLANT WHAT IT THINKS

There are all sorts of liquid chemicals—actually, an almost unlimited number—that you can put a soil sample into, shake, filter and analyze to determine how much of a nutrient is in the liquid. But how can we have confidence that a certain soil test level means that you will probably increase yield by applying that nutrient? And that after a critical test level is passed, there is little chance of increasing yield by applying that nutrient?

Researchers ask the plants. They do this by running experiments over a number of years on many different fields around the state or region. This is done by first taking a soil sample and then laying out plots and applying a few different levels of the nutrient (let’s say P) to the different plots, always including plots that received no added P. When crops are harvested in each plot, it is possible to determine what the plant “thought” about the soil test level. If the plant was not able to get enough of the nutrient in the control plots, there will be a yield increase between those and the plots receiving P application.

Without running these experiments—evaluating yield increases with added fertilizer at different soil test levels—there is no way to know what is considered a “good” soil test. Sometimes people come up with new soil tests that make a splash in the farm press. But until the multi-year effort of correlating a proposed test with plant response is made on a variety of soil and under various weather conditions, it is not possible to know if the test is useful or not. The ultimate word about the quality of a test is whether a crop will respond to added fertilizer the way a test value indicates it should.

Also, this type of research is often first done on small plots on research farms and needs to be validated in fields of commercial farms.

Sources of Confusion About Soil Tests

People may be easily confused about the details of soil tests, especially if they have seen results from more than one soil testing laboratory. There are a number of reasons for this, including:

- laboratories use a variety of procedures;

- labs report results differently; and

- different approaches are used to make recommendations based on soil test results.

Varied Laboratory Procedures

One of the complications with using soil tests to help determine nutrient needs is that testing labs across the world use a wide range of procedures. The main difference among labs is the solutions they use to extract the soil nutrients. Some use one solution for all nutrients, while others will use one solution to extract potassium, magnesium and calcium; another for phosphorus; and yet another for micronutrients. The various extracting solutions have different chemical compositions, so the amount of a particular nutrient that lab A extracts may be different from the amount extracted by lab B. Labs frequently have a good reason for using a particular solution, however. For example, the Olsen test for phosphorus (see Table 21.1) is more accurate for high-pH soils in arid and semiarid regions than the various acid-extracting solutions commonly used in more humid regions. Whatever procedure the lab uses, soil test levels must be calibrated with the crop’s response to added nutrients. For example, do yields increase when you add phosphorus to a soil that tested low in P? In general, university and state labs in a given region use the same or similar procedures that have been calibrated for local soils and climate.

Reporting Soil Test Levels Differently

Soil testing reports are unfortunately not standardized and labs may report their results in different ways. Some use parts per million (10,000 ppm = 1%); some use pounds per acre (usually by using parts per two million, which is twice the ppm level, because 1 acre of soil to 6 inch depth weighs approximately two million pounds) or kilograms per hectare; and some use an index (for example, all nutrients are expressed on a scale of 1–100). Some report Ca, Mg and K in milliequivalents (me) per 100 grams. In addition, some labs report phosphorus and potassium in the elemental form, while others use the oxide forms: P2O5 and K2O. Most testing labs report results as both a number and a category such as low, medium, optimum, high and very high. This is perhaps a more appropriate way to report the results as the relationship between soil test levels and yield response is affected by soil variability and seasonal growing conditions, and these broader categories provide a more realistic sense of the probability that fertilizer applications will increase yields. Most labs consider high to be above the amount needed (the optimum), but some labs use optimum and high interchangeably. (High, and even very high, does not mean that the nutrient is present in toxic amounts; these categories only indicate that there is a very slim chance of getting a yield increase if that nutrient is applied. With regard to P, very high indicates the potential for greater amounts lost in runoff waters, causing environmental problems in surface waters.) If the significance of the various categories is not clear on your report, be sure to ask. Labs should be able to furnish you with the probability of getting a response to added fertilizer for each soil test category.

Different Recommendation Systems

Even when labs use the same procedures, as is the case in most of the Midwest, different approaches to making recommendations lead to different amounts of recommended fertilizer. Three different systems are used to make fertilizer recommendations based on soil tests: 1) the sufficiency level system, 2) the buildup and maintenance system, and 3) the basic cation saturation ratio system (only used for Ca, Mg and K).

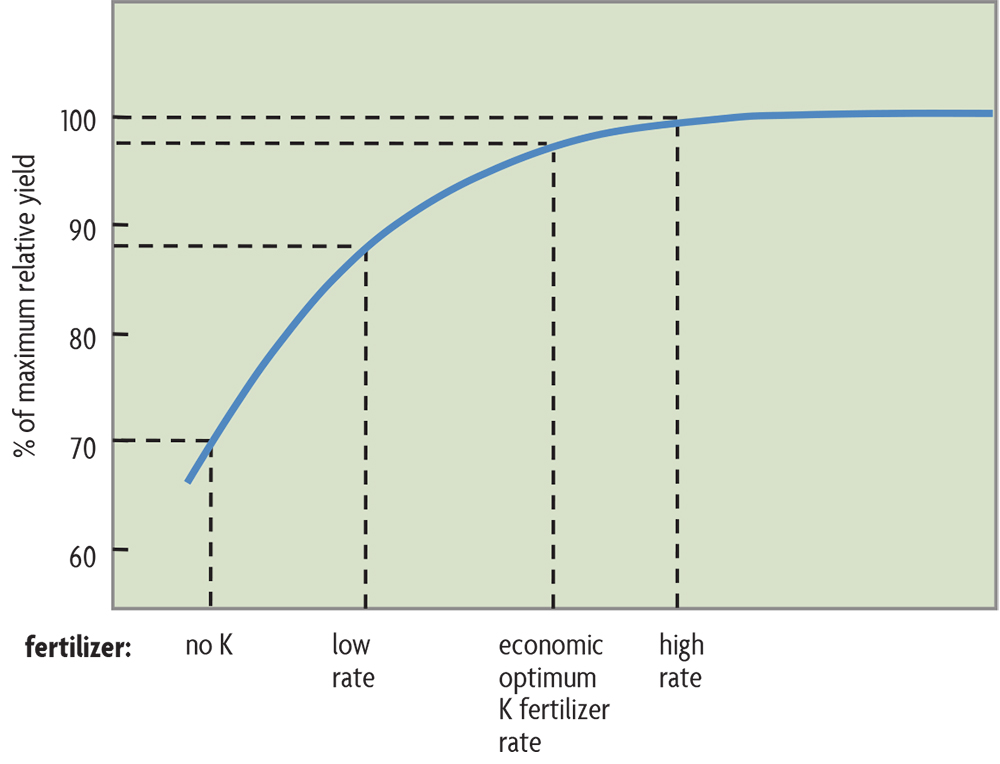

The sufficiency level system suggests that there is a point, the sufficiency or critical soil test value, above which there is little likelihood of crop response to an added nutrient. Its goal is not to produce the highest yield every year but rather to produce the highest average return over time from using fertilizers. Experiments that relate yield increases with added fertilizer to soil test levels provide much of the evidence supporting this approach. When applying fertilizers when soil tests indicate a need (see Figure 21.1 for K applications to a soil with a very low K test), yields increase up to a maximum yield, with no further increases as more fertilizer is added beyond this so-called agronomic optimum rate. Farmers should be aiming not for maximum yield but for the maximum economic yields and the economic optimum rate, which are slightly below the highest possible yields obtained with the agronomic optimum rate. With a higher testing soil than shown in Figure 21.1, let’s say low instead of very low K, there would be less of a yield increase from added K and smaller amounts of fertilizer would be recommended.

The buildup and maintenance system calls for building up soils to high levels of fertility and then keeping them there by applying enough fertilizer to replace nutrients removed in harvested crops. As levels are built up, this approach frequently recommends more fertilizer than the sufficiency system. It is used mainly for phosphorus, potassium and magnesium recommendations; it can also be used for calcium when high-value vegetables are being grown on low-CEC soils. However, there may be a justification for using the buildup and maintenance approach for phosphorus and potassium—in addition to using it for calcium—on high-value crops because 1) the extra costs are such a small percent of total costs and 2) when weather is suboptimal (cool and damp, for example), this approach may occasionally produce a higher yield that would more than cover the extra expense of the fertilizer. Farmers may also want to build up their fertility levels during years of good prices to have a buffer against economic headwinds in future years. If you use this approach, you should pay attention to levels of phosphorus: adding more P when levels are already optimum can pose an environmental risk.

The basic cation saturation ratio system (BCSR—also called the base ratio system), a method for estimating calcium, magnesium and potassium needs, is based on the belief that crops yield best when calcium, magnesium and potassium—usually the dominant cations on the CEC—are in a particular balance. It grew out of work in the 1940s and 1950s by Firman E. Bear and coworkers in New Jersey, and later by William A. Albrecht in Missouri.

This system has become accepted by many farmers despite a lack of modern research supporting it (see “The Basic Cation Saturation Ratio System” at the end of this chapter). Few university testing laboratories use this system, but a number of private labs do continue to use it. It calls for calcium to occupy about 60–80% of the CEC, magnesium to be 10–20%, and potassium 2–5%. This is based on the notion that if the percent saturation of the CEC is good, there will be enough of each of these nutrients to support optimum crop growth. When using the BCSR, it is important to recognize its practical as well as theoretical flaws. For one, even when the ratios of the nutrients are within the recommended crop guidelines, there may be such a low CEC (such as in a sandy soil that is very low in organic matter) that the amounts present are insufficient for crops. If the soil has a CEC of only 2 milliequivalents per 100 grams of soil, for example, it can have a “perfect” balance of Ca (70%), Mg (12.5%) and K (3.5%) but contain only 560 pounds of Ca, 60 pounds of Mg and 53 pounds of K per acre to a depth of 6 inches. Thus, while these elements are in a supposedly good ratio to one another, there isn’t enough of any of them. The main problem with this soil is a low CEC; the remedy would be to add a lot of organic matter over a period of years and, if the pH is low, it should be limed.

The opposite situation also needs attention. When there is a high CEC and satisfactory pH for the crops being grown, even though there is plenty of a particular nutrient, the cation ratio system may call for adding more. This can be a problem with soils that are naturally high in magnesium, because the recommendations may call for high amounts of calcium and potassium to be added when none are really needed, thus wasting the farmer’s time and money.

Research indicates that plants do well over a broad range of cation ratios, as long as there are sufficient supplies of potassium, calcium and magnesium. But still, the ratios sometimes matter for a different reason. For example, liming sometimes results in decreased potassium availability and this would be apparent with the BSCR system, but the sufficiency system would also call for adding potassium, because of the low potassium levels in these limed soils. Also, when magnesium occupies more than 50% of the CEC in soils with low organic matter and low aggregate stability, using gypsum (calcium sulfate) may help restore aggregation because of the extra calcium as well as the higher level of dissolved salts. However, this does not relate to crop nutrition, but results from the higher charge density of Ca promoting better aggregation.

WANT TO LEARN MORE ABOUT BSCR?

The preponderance of research indicates that there is no “ideal” ratio of cations held on the CEC with which farmers should try to bring their soils into conformity. It also indicates that the percent base saturation has no practical usefulness for farmers. If you would like to delve further into this issue, there is a more detailed discussion of BSCR and how it perpetuates a misunderstanding of both CEC and base saturation in the appendix at the end of this chapter.

Plant Tissue Tests

Soil tests are the most common means of assessing fertility needs of crops, but plant tissue tests are especially useful for nutrient management of perennial crops, such as apples, blueberries, peaches, citrus and vineyards. For most annuals, including agronomic and vegetable crops, tissue testing, though not widely used, can help diagnose problems. However, because a large amount of needed fertilizers (aside from nitrogen) can’t usually be delivered to the crop during the season, tissue nutrient tests are best used in combination with soil tests. The small sampling window available for most annuals and an inability to effectively fertilize them once they are well established, except for nitrogen during early growth stages, limit the usefulness of tissue analysis for annual crops. However, leaf petiole nitrate tests are sometimes done on potatoes and sugar beets to help fine-tune in-season nitrogen fertilization. Petiole nitrate is also helpful for nitrogen management of cotton and for managing irrigated vegetables, especially during the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. With irrigated crops, particularly when the drip system is used, fertilizer can be effectively delivered to the rooting zone during crop growth.

To estimate the percentages of the various cations on the CEC, the amounts need to be expressed in terms of quantity of charge. Some labs give concentration by both weight (parts per million, ppm) and charge (milliequivalents per 100 grams, me/100g). If you want to convert from ppm to me/100g, you can do it as follows:

(Ca in ppm)/200 = Ca in me/100g

(Mg in ppm)/120 = Mg in me/100g

(K in ppm)/390 = K in me/100g

As discussed in Chapter 20, adding up the amount of charge due to calcium, magnesium and potassium gives a very good estimate of the CEC for most soils above pH 5.5.

What Should You Do?

After reading the discussion above you may be somewhat confused by the different procedures and ways of expressing results, as well as by the different recommendation approaches. It is bewildering. Our general suggestions for how to deal with these complex issues are as follows:

- Send your soil samples to a lab that uses tests that have been evaluated for the soils and crops of your state or region. Continue using the same lab or another that uses the same system.

- If you’re growing low value-per-acre crops (wheat, corn, soybeans, etc.), be sure that the recommendation system used is based on the sufficiency approach. This system usually results in lower fertilizer rates and higher economic returns for low-value crops. (It is not easy to find out what system a lab uses. Be persistent, and you will get to a person who can answer your question.)

- Dividing a sample in two and sending it to two labs may result in confusion. You will probably get different recommendations, and it won’t be easy to figure out which is better for you, unless you are willing to do a comparison of the recommendations. In most cases you are better off staying with the same trusted lab and learning how to fine-tune the recommendations for your farm. If you are willing to experiment, however, you can send duplicate samples to two different labs, with one going to your state-testing laboratory. In general, the recommendations from state labs call for less, but enough, fertilizer. If you are growing crops over a large acreage, set up a demonstration or experiment in one field by applying the fertilizer recommended by each lab over long strips and see if there is any yield difference. A yield monitor for grain crops would be very useful for this purpose. If you’ve never set up a field experiment before, you should ask your Extension agent for help. You might also find SARE’s publication How to Conduct Research on Your Farm or Ranch of use (download or order in print at www.sare.org/research).

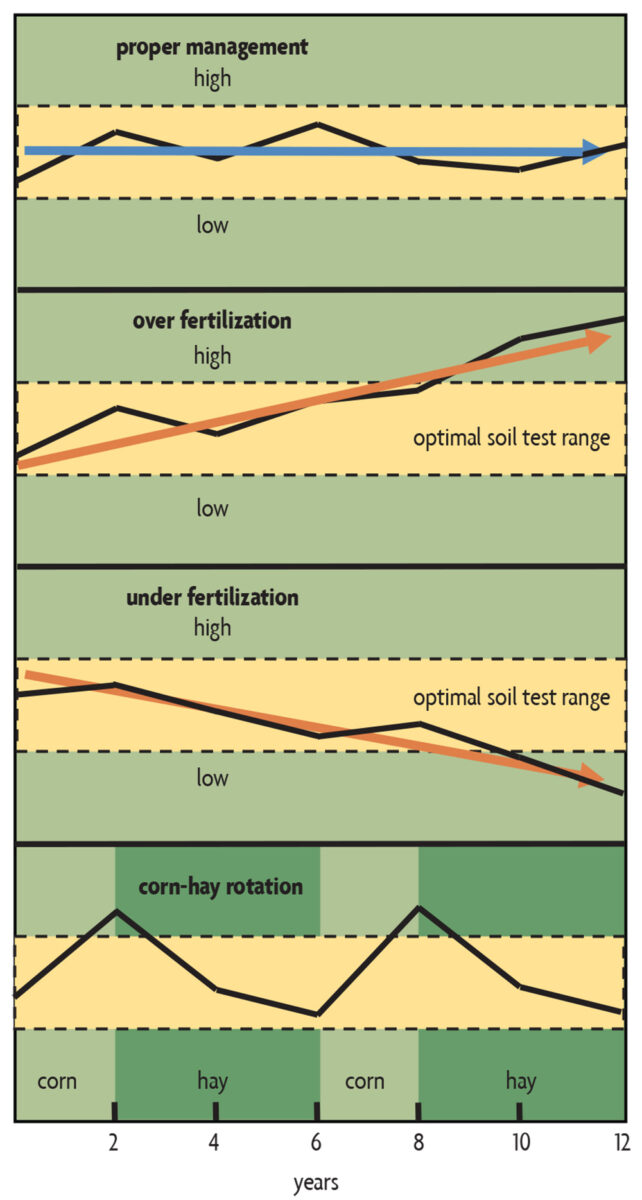

- Keep a record of the soil tests for each field, so that you can track changes over the years (Figure 21.2). (But, again, make sure you use the same lab to keep results comparable). If records show a buildup of nutrients to high levels, reduce nutrient applications. If you’re drawing nutrient levels down too low, start applying fertilizers or off-farm organic nutrient sources. In some rotations, such as the corn-corn-four years of hay shown at the bottom of Figure 21.2, it makes sense to build up nutrient levels during the corn phase and draw them down during the hay phase.

RECOMMENDATION SYSTEM COMPARISON

Most university testing laboratories use the sufficiency level system, but some make potassium or magnesium recommendations by modifying the sufficiency system to take into account the portion of the CEC occupied by the nutrient.

The buildup and maintenance system is used by some state university labs and many commercial labs. An extensive evaluation of different approaches to fertilizer recommendations for agronomic crops in Nebraska found that the sufficiency level system resulted in using less fertilizer and gave higher economic returns than the buildup and maintenance system.

Studies in Kentucky, Ohio and Wisconsin have indicated that the sufficiency system is superior to both the buildup and maintenance and cation ratio systems.

Soil Testing for Nitrogen

As we discussed in Chapter 19, nitrogen management poses exceptional challenges because gains and losses of this nutrient are affected by its complex interactions in soil, crop management decisions and weather factors. The highly dynamic nature of nitrogen availability makes it difficult to estimate how much of the N that crops need can come from the soil. Soil samples for nitrogen tests are therefore usually taken at a different time using a different method than samples for the other nutrients (which are typically sampled to plow depth in the fall or spring).

In the humid regions of the United States there was no reliable soil test for N availability before the mid-1980s. The nitrate test commonly used for corn in humid regions was developed during the 1980s in Vermont. It is usually called the pre-sidedress nitrate test (PSNT) but is also called the late spring nitrate test (LSNT) in parts of the Midwest. In this test a soil sample is taken to a depth of 1 foot when corn is between 6 inches and 1 foot tall. The original idea behind the test was to wait as long as possible before sampling because soil and weather conditions in the early growing season may reduce or increase N availability for the crop later in the season. After the corn is 1 foot tall, it is difficult to get samples to a lab and back in time to apply any needed sidedress N fertilizer. The PSNT is now used on field corn, sweet corn, pumpkins and cabbage. Although it is widely used, it is not very accurate in some situations, such as the sandy coastal plains soils of the southeastern United States.

Different approaches to using the PSNT work for different farms. In general, using the soil test allows a farmer to avoid adding excess amounts of “insurance fertilizer.”

Two contrasting examples:

- For farms using rotations with legume forages and applying animal manures regularly (so there’s a lot of active soil organic matter), the best way to use the test is to apply only the amount of manure necessary to provide sufficient N to the plant. The PSNT will indicate whether the farmer needs to side dress any additional N fertilizer. It will also indicate whether the farmer has done a good job of estimating N availability from manures.

- For farms growing cash grains without using legume cover crops, it’s best to apply a conservative amount of fertilizer N before planting and then use the test to see if more is needed. This is especially important in regions where rainfall cannot always be relied upon to quickly bring fertilizer into contact with roots. The PSNT provides a backup and allows the farmer to be more conservative with preplant applications, knowing that there is a way to make up any possible deficit. Be aware that if the field receives a lot of banded fertilizer before planting (like injected anhydrous ammonia), test results may be very variable depending on whether cores are collected from the injection band or not.

| Table 21.1 Phosphorus Soil Tests Used in Different Regions | |

|---|---|

| Region | Soil test solutions used for P |

| Arid and semiarid Midwest, west, and northwest | Olsen AB-DTPA |

| Humid Midwest, mid-Atlantic, Southeast, and eastern Canada | Mehlich 3 Bray 1 (also called Bray P-1 or Bray-Kurtz P) |

| North central and Midwest | Bray 1 (also called Bray P-1 or Bray-Kurtz P) |

| Washington and Oregon | Bray 1 for acidic soils Olsen for alkaline soils |

| Southeast and mid-Atlantic | Mehlich 1 |

| Northeast (New York and parts of New England), some labs in Idaho and Washington | Morgan or modified Morgan Mehlich 3 |

| Source: Modified from Allen, Johnson and Unruh et al. (1994) | |

| Table 21.2 Interpretation Ranges for Different P Soil Tests* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low and medium | Optimum | High | |

| Olsen | 0–11 | 11–16** | >16 |

| Morgan | 0–4 | 4–10 | >10 |

| Bray 1 (Bray P-1) | 0–25 | 25–45 | >45 |

| Mehlich 1 | 0–20 | 20–40 | >40 |

| Mehlich 3 | 0–30 | 30–50 | >50 |

| AB-DTPA (for irrigated crops) | 0–8 | 8–11 | >12 |

| *Individual laboratories may use somewhat different ranges for these categories or use different category names. Also note: Units are in parts per million phosphorus (ppm P), and ranges used for recommendations may vary from state to state; Low and Medium indicates a high to moderate probability to increase yield by adding P fertilizer; Optimum indicates that there is a low probability for increasing yield with added P fertilizer; High soil test levels indicate increasing potential for P pollution in runoff. Some labs also have a Very High category. **If the soil is calcareous (has free calcium carbonate in the soil), the Olsen soil test “optimum” range would be higher, with over 25 ppm soil test P for a zero P fertilizer recommendation. | |||

Other Nitrogen Soil Tests

In humid regions there is no other widely used soil test for N availability. A few states in the upper Midwest offer a pre-plant nitrate test, which calls for sampling to 2 feet in the spring. For a number of years there was considerable interest in the Illinois Soil Nitrogen Test (ISNT). The ISNT, which measures the amino-sugar portion of soil N, has unfortunately been found to be an inconsistent predictor of whether the plant needs extra N. An evaluation in six Midwestern states concluded that it is not sufficiently precise for making N fertilizer recommendations. Another proposed test involves combining soluble organic N and carbon together with the amount of CO2 that is evolved when the soil is rewetted. These tests, individually or in combination, have not yet been widely evaluated for predicting N needs under field conditions.

In the drier parts of the country, in the absence of a soil test, many land grant university laboratories use organic matter content to help adjust a fertilizer recommendation for N. But there is also a soil nitrate soil test used in some drier states that requires samples to 2 feet or more, and it has been used with success since the 1960s. The deep-soil samples can be taken in the fall or early spring, before the growing season, because of low leaching and denitrification losses and low levels of active organic matter (so hardly any nitrate is mineralized from organic matter). Soil samples can be taken at the same time for analysis for other nutrients and pH.

Sensing and Modeling Nitrogen Deficiencies

Since nitrogen management is a challenge for many of the common crops (corn, wheat, rice, oilseed rape, etc.) and is also an expensive input, there has been a significant amount of research into new technologies that allow a farmer or consultant to assess a crop’s N status during the season. Generally four types of approaches are used:

- Chlorophyll meters are handheld devices that indirectly estimate chlorophyll content in a crop leaf, which is an indicator of its N status (Figure 21.3, left). It requires field visits and adequate leaf sampling to represent different zones in the field. They are primarily used for final fertilizer applications in cereals, especially when aiming for certain protein contents.

- Canopy reflectance sensors can be handheld or equipment-mounted devices that measure reflectance without contacting the leaf (Figure 21.3, right). Both sense the light reflectance properties of a crop canopy in the near infrared and red (or red-edge) bands, which can be related to crop growth and N uptake. When equipment mounted, it allows for on-the-go adjustment of N rates throughout a field, which in most cases also requires the establishment of a high-N reference strip in the field for use in calibrating the sensor. These sensors are not imaging; in other words, they don’t create pixel maps, but they can be linked with GPS signals to chart patterns in a field.

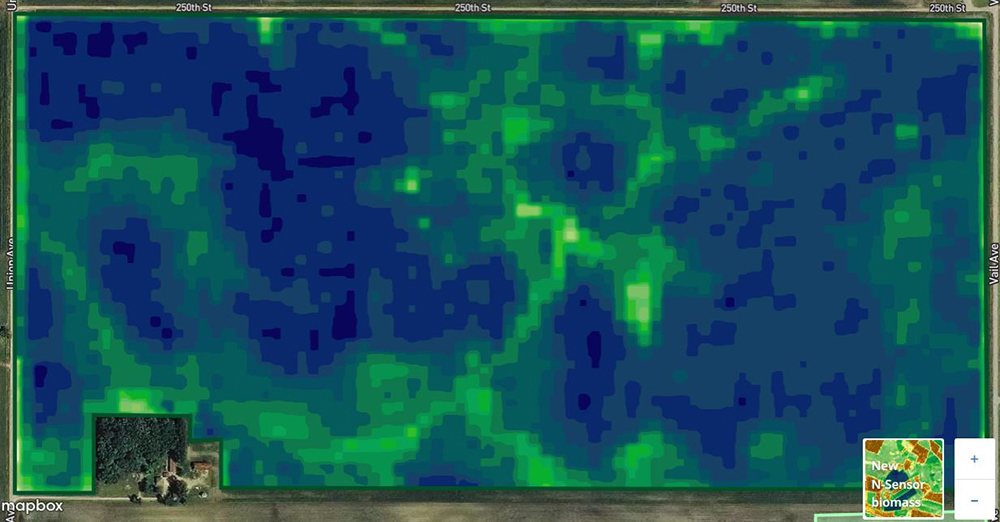

- Satellite, aircraft or drone imagery can be used to extract reflectance information that can be related to a crop’s N status (Figure 21.4, left), usually also using near infrared and red/red-edge bands, with resolutions in the 30–90 foot (10–30 meter) range.

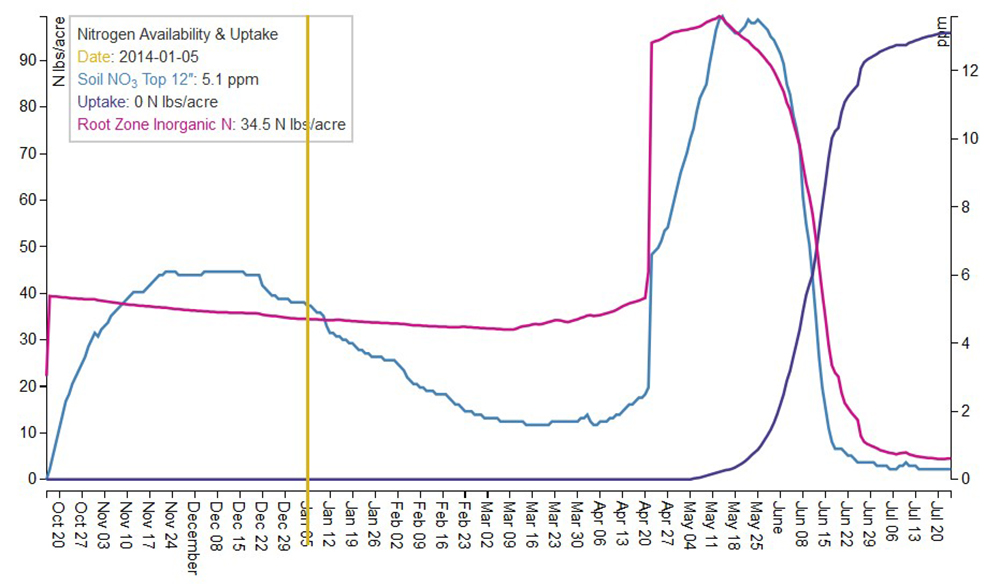

- Computer models simulate a field’s N dynamics and allow for daily estimation of the soil and crop N status (Figure 21.4, right).

These tools are actively being advanced as part of the drive towards digital technologies in crop production. Each technology has its strengths and weaknesses, and has proven different levels of precision. Use of computer models is relatively inexpensive and scalable. It allows for daily monitoring and is good at integrating other data sources into recommendations, but it does not involve direct field observations. The satellite-derived images are generally available every few days but are highly impacted by cloud cover, which can obstruct fields during critical decision times. Aircraft and drone imaging can avoid cloud issues but are more expensive. The chlorophyll meter is an in-field measurement that is, like the PSNT, relatively labor intensive and costly to repeat for large fields (but more attractive with smaller fields with high-value crops). Canopy reflectance sensors are also generally used once or twice during the season when N fertilizer is applied, but they are not used for continuous monitoring.

Soil Testing for P

Soil test procedures for phosphorus are different than those for nitrogen. When testing for phosphorus, the soil is usually sampled to plow depth in the fall or in the early spring before tillage, and the sample is usually analyzed for phosphorus, potassium, sometimes other nutrients (such as calcium, magnesium and micronutrients) and pH. The methods used to estimate available P vary from region to region and sometimes from state to state within a region (Table 21.1). Although the relative test value for a given soil is usually similar according to different soil tests (for example, a soil testing high in P by one procedure is generally also high by another procedure), the actual numbers can be different (Table 21.2).

The various soil tests for P take into account a large portion of the available P contained in recently applied manures and the amount that will become available from the soil minerals. However, if there is a large amount of active organic matter in your soils from crop residues or manure additions in previous years, there may well be more available P for plants than indicated by the soil test. (While there is no comparable in-season test for P, the PSNT reflects the amount of N that may become available from decomposing organic matter.)

Testing Soils for Organic Matter

A word of caution when comparing your soil test organic matter levels with those discussed in this book. If your laboratory reports organic matter as “weight loss” at high temperature, the numbers may be higher than if the lab uses the original wet chemistry method. A soil with 3% organic matter by wet chemistry might have a weight-loss value of between 4% and 5%. Most labs use a correction factor to approximate the value you would get by using the wet chemistry procedure. Although either method can be used to follow changes in your soil, when you compare soil organic matter of samples run in different laboratories, it’s best to make sure the same method was used. Unfortunately, despite its importance, organic matter assessment is still poorly standardized and lab-to-lab variability remains high. It is therefore best to use the same lab year after year if you want to evaluate trends in your fields.

There is now a laboratory that will determine various forms of living organisms in your soil. Although it costs quite a bit more than traditional testing for nutrients or organic matter, you can find out the amount (weight) of fungi and bacteria in a soil, as well as obtain an analysis for other organisms. (See the “Resources” section for laboratories that run tests in addition to basic soil fertility analysis.)

Testing Soils for pH, Lime Needs

Soil pH and how to change it was discussed in Chapter 20. If a soil’s pH is low, indicating that it is acid, one of the common ways to determine the amount of lime to be applied is to place a sample of soil in a chemical buffer and measure the amount the acid soil is able to depress the buffer’s pH. Keep in mind that this is different from the soil’s pH, which indicates whether liming is needed. The degree of change of the buffer’s pH is an indication of how much lime needs to be applied to raise the soil pH to the desired level.

Interpreting Soil Test Results

Below are four soil test examples, including discussion about what they tell us and what types of practices farmers should follow to satisfy plant nutrient needs on these soils. Suggestions are provided for conventional farmers and for organic producers. These are just suggestions; there are other satisfactory ways to meet the needs of crops growing on the soils sampled. The soil tests were run by different procedures to provide examples from around the United States. Interpretations of a number of commonly used soil tests—relating test levels to general fertility categories—are given later in the chapter (see tables 21.3 and 21.4). Many labs estimate the CEC that would exist at pH 7 (or even higher). Because we feel that the soil’s current CEC is of most interest (see Chapter 20), the CEC is estimated by summing the exchangeable bases. The more acidic a soil, the greater the difference between its current CEC and the CEC it would have near pH 7.

Following the four soil tests below is a section on modifying recommendations for particular situations.

UNUSUAL SOIL TESTS

We’ve come across unusual soil test results from time to time. A few examples and their typical causes:

- Very high phosphorus levels: high poultry or other manure application over many years.

- Very high salt concentration in humid regions: recent application of large amounts of poultry manure in high tunnel greenhouses where rainfall is not able to leach salts, or located immediately adjacent to a road where deicing salt was used.

- Very high pH and high calcium levels relative to potassium and magnesium: large amounts of lime-stabilized sewage sludge used.

- Very high calcium levels given the soil’s texture and organic matter content: the soil test used an acid solution, such as the Morgan, Mehlich 1 or Mehlich 3, to extract soils containing free limestone, causing some of the lime to dissolve.

- Soil pH >7 and very low P: the soil test used an acid such as found in Mehlich I, Bray or Mehlich 3 on an alkaline, calcareous soil. (In this case, the soil neutralizes much of the acid, so little P is extracted.)

| SOIL TEST #1 (New England) Soil Test #1 Report Summary* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name: North Sample date: September (PSNT sample taken the following June) Soil type: loamy sand Manure added: none Cropping history: mixed vegetables Crop to be grown: mixed vegetables | MEASUREMENT | LBS/ACRE** | PPM** | Soil Test CATEGORY | Recommendation SUMMARY |

| P | 4 | 2 | low | 50–70 lbs P2O5/acre | |

| K | 100 | 50 | low | 150–200 lbs K2O/acre | |

| Mg | 60 | 30 | low | lime (see below) | |

| Ca | 400 | 200 | low | lime (see below) | |

| pH | 5.4 | liming material needed | |||

| buffer pH*** | 6 | 2 tons dolomitic limestone/acre | |||

| CEC**** | 1.4 me/100g | ||||

| OM | 1% | add organic matter: compost, cover crops, animal manures | |||

| PSNT | 5 | low | side dress 80–100 lbs N/acre | ||

| *Nutrients were extracted by modified Morgan’s solution (see Table 21.3A for interpretations). **Some labs report results in pounds per acre while others report results as ppm. ***The pH of a soil sample added to a buffered solution; the lower the pH, the more lime is needed. ****CEC by sum of bases. The estimated CEC would probably double if “exchange acidity” were determined and added to the sum of bases. Note: ppm = parts per million; P = phosphorus; K = potassium; Mg = magnesium; Ca = calcium; OM = organic matter; me = milliequivalent; PSNT = pre-sidedress nitrate test; N = nitrogen. | |||||

What can we tell about soil #1 based on the soil test?

- The pH indicates that the soil is too acidic for most agricultural crops, so lime is needed. The buffer pH indicates that around 2 tons per acre is needed to raise pH to 6.5.

- Phosphorus is low, as are potassium, magnesium and calcium. All should be applied.

- This low-organic-matter soil is probably also low in active organic matter (indicated by the low PSNT test, see Table 21.4A) and will need an application of nitrogen. (The PSNT is done during crop growth, so it is difficult to use manure to supply extra N needs indicated by the test.)

- The coarse texture of the soil is indicated by the combination of low organic matter and low CEC.

Recommendations for conventional growers

- Apply dolomitic limestone, if available, in the fall at about 2 tons per acre (work it into the soil, and establish a cover crop if possible). This will take care of the calcium and magnesium needs at the same time as the soil’s pH is increased. It will also help make soil phosphorus more available, as well as increase the availability of any added phosphorus.

- Because no manure is to be used after the test is taken, broadcast significant amounts of phosphate (P2O5 —probably around 50–70 pounds per acre) and potash (K2O—around 150–200 pounds per acre). Some phosphate and potash can also be applied in starter fertilizer (band-applied at planting). Usually, N is also included in starter fertilizer, so it might be reasonable to use about 300 pounds of a 10-10-10 fertilizer, which will apply 30 pounds of N, 30 pounds of phosphate and 30 pounds of potash per acre. If that rate of starter is to be used, broadcast 400 pounds per acre of a 0-10-30 bulk blended fertilizer. The broadcast plus the starter will supply 30 pounds of N, 70 pounds of phosphate and 150 pounds of potash per acre.

- If only calcitic (low-magnesium) limestone is available, use K-Mag (Sul-Po-Mag) as the potassium source in the bulk blend to help supply magnesium.

- Nitrogen should be side dressed at around 80–100 (or more) pounds per acre for N-demanding crops such as corn or tomatoes. About 220 pounds of urea per acre will supply 100 pounds of N.

- Use various medium- to long-term strategies to build up soil organic matter, including the use of cover crops and animal manures. Most of the nutrient needs of crops on this soil could have been met by using about 20 tons wet weight of solid cow manure per acre or its equivalent. It is best to apply it in the spring, before planting. If the manure had been applied, the PSNT test would probably have been quite a bit higher, perhaps around 25 ppm.

Recommendations for organic producers

- Use dolomitic limestone to increase the pH (as recommended for the conventional farmer, above). It will also help make soil phosphorus more available, as well as increase the availability of any added phosphorus.

- Apply 2 tons of rock phosphate or a combination of 1 ton rock phosphate and 2.5 tons of poultry manure.

- If poultry manure is used to raise the phosphorus level without using rock phosphate, add 2 tons of compost per acre to provide some longer lasting nutrients and humus. If rock phosphate is used to supply phosphorus and if no poultry manure is used, use livestock manure and compost (to add N, potassium, magnesium and some humus).

- Establish a good rotation with soil-building crops and legume cover crops. Use manure with care. Although the application of uncomposted manure is allowed by organic certification agencies, there are restrictions. Under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the application of uncomposted manure is now regulated for all farms growing food crops, whether organic or not. For example, four months may be needed between the time you apply uncomposted manure and either harvest crops with edible portions in contact with soil or plant crops that accumulate nitrate, such as leafy greens or beets. A three-month period may be needed between uncomposted manure application and harvest of other food crops. These FSMA rules apply to all farms with annual sales of more than $25,000.

| SOIL TEST #2 (Humid Midwest) Soil Test #2 Report Summary* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name: #12 Sample date: December (no sample for PSNT will be taken) Soil type: clay (somewhat poorly drained) Manure applied: none Cropping history: continuous corn Crop to be grown: corn | Measurement | LBS/ACRE** | PPM** | Soil Test CATEGORY | Recommendation SUMMARY |

| P | 20 | 10 | very low | 30 lbs P2O5/acre | |

| K | 58 | 29 | very low | 200 lbs K2O/acre | |

| Mg | 138 | 69 | high | none | |

| Ca | 8,168 | 4,084 | high | none | |

| pH | 6.8 | no lime needed | |||

| CEC | 21.1 me/100g | ||||

| OM | 4.3% | rotate to forage legume crop | |||

| N | no N soil test | 100–130 lbs N/acre | |||

| *All nutrient needs were determined using the Mehlich 3 solution (see Table 21.3C). **Most university laboratories in the Midwestern United States report results as ppm while private labs may report results in pounds per acre. Note: ppm = parts per million; P = phosphorus; K = potassium; Mg = magnesium; Ca = calcium; N = nitrogen; OM = organic matter; me = milliequivalent. | |||||

What can we tell about soil #2 based on the soil test?

- The high pH indicates that this soil does not need any lime.

- Phosphorus and potassium are low. (Note: 20 pounds of P per acre is low, according to the soil test used, Mehlich 3. If another test, such as Morgan’s solution, was used, a result of 20 pounds of P per acre would be considered a high result.)

- The organic matter is relatively high. However, considering that this is a somewhat poorly drained clay, it probably should be even higher.

- About half of the CEC is probably due to the organic matter and the rest probably due to the clay.

- Low potassium indicates that this soil has probably not received high levels of manures recently.

- There was no test done for nitrogen, but given the field’s history of continuous corn and little manure, there is probably a need for nitrogen.

- A low amount of active organic matter that could have supplied nitrogen for crops is indicated by the history (the lack of rotation to perennial legume forages and the lack of manure use) and the moderate percent of organic matter (considering that it is a clay soil).

General recommendations

- This field should probably be rotated to a perennial forage crop.

- Phosphorus and potassium are needed. If a forage crop is to be grown, probably around 30 pounds of phosphate and 200 or more pounds of potash should be broadcasted pre-planting. If corn will be grown again, all of the phosphate and 30–40 pounds of the potash can be applied as starter fertilizer at planting. Although magnesium, at about 3% of the effective CEC, would be considered low by relying exclusively on a basic cation saturation ratio system recommendation, there is little likelihood of an increase in crop yield or quality by adding magnesium.

- Nitrogen fertilizer is probably needed in large amounts (100–130 pounds per acre) for high N-demanding crops, such as corn. If no in-season soil test (like the PSNT) is done, some pre-plant N should be applied (around 50 pounds per acre), some in the starter band at planting (about 15 pounds per acre) and some side dressed (about 50 pounds).

- One way to meet the needs of the crop:

- broadcast 500 pounds per acre of an 11-0-44 bulk blended fertilizer;

- use 300 pounds per acre of a 5-10-10 starter; and then

- side dress with 110 pounds per acre of urea. These amounts will supply approximately 120 pounds of N, 30 pounds of phosphate and 210 pounds of potash.

Recommendations for organic producers

- Apply 2 tons per acre of rock phosphate (to meet P needs) or a combination of 1 ton rock phosphate and 3–4 tons of poultry manure.

- Apply 400 pounds of potassium sulfate per acre broadcast pre-plant if a combination of rock phosphate and poultry manure is applied to meet P needs.

- Use manure with care. Although the application of uncomposted manure is allowed by organic certification agencies, there are restrictions. Under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the application of uncomposted manure is now regulated for all farms growing food crops, whether organic or not. For example, four months may be needed between the time you apply uncomposted manure and either harvest crops with edible portions in contact with soil or plant crops that accumulate nitrate, such as leafy greens or beets. A three-month period may be needed between uncomposted manure application and harvest of other food crops. These FSMA rules apply to all farms with annual sales of more than $25,000.

| SOIL TEST #3 (Alabama) Soil Test #3 Report Summary* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name: River A Sample date: October Soil type: sandy loam Manure applied: poultry manure in previous years Cropping history: continuous cotton Crop to be grown: cotton | Measurement | LBS/ACRE | PPM** | Soil Test CATEGORY | Recommendation SUMMARY |

| P | 60 | 30 | high | none | |

| K | 166 | 83 | high | none | |

| Mg | 264 | 132 | high | none | |

| Ca | 1,158 | 579 | none | ||

| pH | 6.5 | no lime needed | |||

| CEC | 4.2 me/100g | ||||

| OM | not requested | use legume cover crops, consider crop rotation | |||

| N | no N soil test | 70–100 lbs N/acre | |||

| *All nutrient needs were determined using the Mehlich 1 solution (seeTable 21.3B). **Alabama reports nutrients in lbs/acre. Note: P = phosphorus; K = potassium; Mg = magnesium; Ca = calcium; N = nitrogen; OM = organic matter; me = milliequivalent. | |||||

What can we tell about soil #3 based on the soil test?

- With a pH of 6.5, this soil does not need any lime.

- Phosphorus, potassium and magnesium are sufficient.

- Magnesium is high, compared with calcium (Mg occupies over 26% of the CEC).

- The low CEC at pH 6.5 indicates that the organic matter content is probably around 1–1.5%.

General recommendations

- No phosphate, potash, magnesium or lime is needed.

- Nitrogen should be applied, probably in a split application totaling about 70–100 pounds N per acre.

- This field should be in a rotation such as cotton-corn-peanuts with winter cover crops.

Recommendations for organic producers

- Although poultry or dairy manure can meet the crop’s needs, that means applying phosphorus on a soil already high in P. If there is no possibility of growing an overwinter legume cover crop (see recommendation #2), about 15–20 tons of bedded dairy manure (wet weight) should be sufficient. Another option for supplying some of the crop’s need for N without adding more P is to use Chilean nitrate until good rotations with legume cover crops are established.

- If time permits, plant a high-N-producing legume cover crop, such as crimson clover (or a crimson clover/oat mix), to provide nitrogen to cash crops.

- Develop a good rotation so that all the needed nitrogen will be supplied to nonlegumes between the rotation crops and cover crops.

- Use manure with care. Although the application of uncomposted manure is allowed by organic certification agencies, there are restrictions. Under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the application of uncomposted manure is now regulated for all farms growing food crops, whether organic or not. For example, four months may be needed between the time you apply uncomposted manure and either harvest crops with edible portions in contact with soil or plant crops that accumulate nitrate, such as leafy greens or beets. A three-month period may be needed between uncomposted manure application and harvest of other food crops. These FSMA rules apply to all farms with annual sales of more than $25,000.

| SOIL TEST #4 (Semiarid Great Plains) Soil Test #4 Report Summary* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name: Hill Sample date: April Soil type: silt loam Manure added: none indicated Cropping history: not indicated Crop to be grown: corn | Measurement | LBS/ACRE | PPM | Soil Test CATEGORY | Recommendation SUMMARY |

| P | 14 | 7 | low | 20–40 lbs P2O5 | |

| K | 716 | 358 | very high | none | |

| Mg | 340 | 170 | high | none | |

| Ca | not determined | none | |||

| pH | 8.1 | no lime needed | |||

| CEC | not determined | ||||

| OM | 1.8% | use legume cover crops, consider rotation to other crops that produce large amounts of residues | |||

| N | 5.8 ppm | 170 lbs N/acre | |||

| *K and Mg are extracted by neutral ammonium acetate, P by the Olsen solution (see Table 21.3D). Note: ppm = parts per million; P = phosphorus; K = potassium; Mg = magnesium; Ca = calcium; OM = organic matter; me = milliequivalent; N = nitrogen, with residual nitrate determined in a surface to 2-foot sample. | |||||

What can we tell about soil #4 based on the soil test?

- The pH of 8.1 indicates that this soil is most likely calcareous.

- Phosphorus is low, there is sufficient magnesium and potassium is very high.

- Although calcium was not determined, there will be plenty in a calcareous soil.

- The organic matter at 1.8% is low for a silt loam soil.

- The nitrogen test indicates a low amount of residual nitrate (Table 21.4B) and, given the low organic matter level, a low amount of N mineralization is expected.

General recommendations

- No potash, magnesium or lime is needed.

- About 150 pounds of N per acre should be applied. Because of the low amount of leaching in this region, most can be applied preplant, with perhaps 30 pounds as a starter (applied at planting). Using 300 pounds per acre of a 10-10-0 starter would supply all P needs (see recommendation #3) as well as provide some N near the developing seedling. Broadcasting and incorporating 260 pounds of urea (or applying subsurface using a liquid formulation) will provide 120 pounds of N.

- About 20–40 pounds of phosphate is needed per acre. Apply the lower rate as a starter because localized placement results in more efficient use by the plant. If phosphate is broadcast, apply at the 40-pound rate.

- The organic matter level of this soil should be increased. This field should be rotated to other crops, and cover crops should be used regularly.

Recommendations for organic producers

- Because rock phosphate is so insoluble in high-pH soils, it would be a poor choice for adding P. Poultry manure (about 6 tons per acre) or dairy manure (about 25 tons wet weight per acre) can be used to meet the crop’s needs for both N and P. However, that means applying more P than is needed, plus a lot of potash (which is already at very high levels). Fish meal might be a good source of N and P without adding K.

- A long-term strategy needs to be developed to build soil organic matter, including better rotations, use of cover crops and importing organic residues onto the farm.

- Use manure with care. Although the application of uncomposted manure is allowed by organic certification agencies, there are restrictions. Under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the application of uncomposted manure is now regulated for all farms growing food crops, whether organic or not. For example, four months may be needed between the time you apply uncomposted manure and either harvest crops with edible portions in contact with soil or plant crops that accumulate nitrate, such as leafy greens or beets. A three-month period may be needed between uncomposted manure application and harvest of other food crops. These FSMA rules apply to all farms with annual sales of more than $25,000.

Adjusting a Soil Test Recommendation

Specific recommendations must be tailored to the crops you want to grow, as well as to other characteristics of the particular soil, climate and cropping system. Most soil test reports use information that you supply about manure use and previous crops to adapt a general recommendation to your situation. However, once you feel comfortable with interpreting soil tests, you may also want to adjust the recommendations for a particular need. What happens if you decide to apply manure after you sent in the form along with the soil sample? Also, you usually don’t get credit for the nitrogen produced by legume cover crops because most forms don’t even ask about their use. The amount of available nutrients from legume cover crops and from manures is indicated in Table 21.5. If you don’t test your soil annually, and the recommendations you receive are only for the current year, you need to figure out what to apply the next year or two, until the soil is tested again.

No single recommendation, based only on the soil test, makes sense for all situations. For example, your gut might tell you that a test is too low (and fertilizer recommendations are too high). Let’s say that although you broadcast 100 pounds N per acre before planting, a high rate of N fertilizer is recommended by the in-season nitrate test (PSNT), even though there wasn’t enough rainfall to leach out nitrate or cause much loss by denitrification. In that case, you might not want to apply the full amount recommended. Another example: A low potassium level in a soil test—let’s say around 40 ppm (or 80 pounds per acre)—will certainly mean that you should apply potassium. But how much should you use? When and how should you apply it? The answer to these two questions might be quite different on a low organic matter, sandy soil where high amounts of rainfall normally occur during the growing season (in which case, potassium may leach out if applied the previous fall or early spring) versus a high organic matter, clay loam soil that has a higher CEC and will hold on to potassium added in the fall. This is the type of situation that dictates using reputable labs whose recommendations are developed for soils and cropping systems in your home state or region. It also is an indication that you may need to modify a recommendation for your specific situation.

Table 21.3

Soil Test Categories for Various Extracting Solutions

| A. Modified Morgan’s Solution (Vermont) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Very low | Low | Optimum | High | Excessive |

| Probability of response to added nutrient | Very high | High | Low | Very low | |

| Available P (ppm) | 0–2 | 2.1–4 | 4.1–7 | 7.1–20 | |

| K (ppm) | 0–50 | 51–100 | 101–130 | 131–160 | >160 |

| Mg (ppm) | 0–35 | 36–50 | 51–100 | >100 | |

| B. Mehlich 1 Solution (Alabama)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Very low | Low | Optimum | High | Excessive |

| Probability of response to added nutrient | Very high | High | Low | Very low | |

| Available P (lbs/A)** | 0–6 | 7–12 | 50 | 26–50 | >50 |

| K (lbs/A)** | 0–22 | 23–45 | 160–90 | >90 | |

| Mg (lbs/A)** | 0–25 | >50 | |||

| Ca for tomatoes (lbs/A)*** | 0–150 | 151–250 | >500 | ||

| *For loam soils (with CEC values of 4.6–9), from: Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station. 2012. Nutrient Recommendation Tables for Alabama Crops. Agronomy and Soils Departmental Series No. 324B. **For corn, legumes and vegetables on soils with CECs greater than 4.6 me/100g. ***For corn, legumes and vegetables on soils with CECs from 4.6–9 me/100g. | |||||

| C. Mehlich 3 Solution (North Carolina)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Very low | Low | Optimum | High | Excessive |

| Probability of response to added nutrient | Very high | High | Low | Very low | |

| Available P (ppm) | 0–12 | 13–25 | 26–50 | 51–125 | >125 |

| K (ppm) | 0–43 | 44–87 | 88–174 | >174 | |

| Mg (ppm) | 0–25 | >25 | |||

| *Source: Hanlon (1998) **Percent of CEC is also a consideration. | |||||

| D. Neutral Ammonium Acetate Solution for K and Mg and Olsen or Bray-1 for P (Nebraska [P and K], Minnesota [Mg]) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Very low | Low | Optimum | High | Excessive |

| Probability of response to added nutrient | Very high | High | Low | Very low | |

| P (Olson, ppm)) | 0–3 | 4–10 | 11–16 | 17–20 | >20 |

| P (Bray-1, ppm) | 0–5 | 6–15 | 16–24 | 25–30 | >30 |

| K (ppm) | 0–40 | 41–74 | 75–124 | 125–150 | >150 |

| Mg (ppm) | 0–50 | 51–100 | >101 | ||

Table 21.4 Soil Test Categories for Nitrogen Tests

| A. Pre-Sidedress Nitrate Test (PSNT)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Very low | Low | Optimum | High | Excessive |

| Probability of response to added nutrient | Very High | High | Low | Very low | |

| Nitrate-N (ppm) | 0-10 | 11-22 | 23-28 | 29-35 | >35 |

| *Soil sample taken to 1 foot when corn is 6–12 inches tall. | |||||

| B. Deep (4-ft) Nitrate Test (Nebraska) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Very low | Low | Optimum | High | Excessive |

| Probability of response to added nutrient | Very High | High | Low | Very low | |

| Nitrate-N (ppm) | 0–6 | 7–15 | 15–18 | 19–25 | >25 |

| Table 21.5 Amounts of Available Nutrients from Manures and Legume Cover Crops | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Legume cover crops* | N lbs/acre | ||

| Hairy vetch | 70–140 | ||

| Crimson clover | 40-90 | ||

| Red and white clovers | 40–90 | ||

| Medics | 30–80 | ||

| Manures** | N | P2O5 lbs per ton manure | K2O |

| Dairy | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Poultry | 20 | 15 | 10 |

| Hog | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| *The amount of available N varies with the amount of growth. **The amount of nutrients varies with diet, storage and application method. Note: Quantities given in this table are somewhat less than for the total amounts given in Table 12.1. | |||

Making Adjustments to Fertilizer Application Rates

If information about cropping history, cover crops and manure use is not provided to the soil testing laboratory, the report containing the fertilizer recommendation cannot take those factors into account. The “Worksheet for Adjusting Fertilizer Recommendations” is an example of how you can modify the report’s recommendations. New computer models have been developed that integrate this type of information—soil test results, manure applications, previous rotation and cover crops, and enhanced efficiency products—with other soil, management and weather data to better estimate the combined dynamic impacts of various N sources and to fine-tune fertilizer applications.

| Worksheet for Adjusting Fertilizer Recommendations Note: This sample worksheet is based on the following scenario: Past crop = corn; Cover crop = crimson clover, but small to medium amount of growth; Manure = 10 tons of dairy manure that tested at 10 pounds of N, 3 pounds of P2O5 and 9 pounds of K2O per ton. (A decision to apply manure was made after the soil sample was sent, so the recommendation could not take those nutrients into account.) | |||

| Soil test recommendation (lbs/acre) | N 120 | P2O5 40 | K2O 140 |

| Accounts for contributions from the soil. Accounts for nutrients contributed from manure and previous crop only if information is included on form sent with soil sample. | |||

| Credits | |||

| (Use only if not taken into account in recommendation received from lab.) Previous crop (already taken into account) Manure (10 tons @ 6 lbs N, 2.4 lbs P2O5, 9 lbs K2O per ton, assuming that 60% of the nitrogen, 80% of the phosphorus and 100% of the potassium in the manure will be available this year) Cover crop (medium-growth crimson clover) | 0 -60 -50 | -24 | -90 |

| Total nutrients needed from fertilizer | 10 | 16 | 50 |

Managing Field Nutrient Variability

Many large fields have considerable variation in soil types and fertility levels. Site-specific application of crop nutrients and lime using variable-rate technology may be economically and environmentally advantageous for these situations. Soil pH levels, P and K often show considerable variability across a large field because of non-uniform application of fertilizers and manures, natural variability and differing crop yields. Soil N levels may also show some variation due to variable organic matter levels and drainage in a field. It has become easier to accurately apply different amounts of N fertilizer to separate parts of fields using the variable fertilizer application technology now available. And, as mentioned above, on-the-go sensors, models and satellite imagery may be used to guide variable application tools (figures 21.3 and 21.4).

Aside from when automated sensors and models are used to determine nitrogen fertilizer needs, site-specific management requires the collection of multiple soil samples within the field, which are then analyzed separately. This is most useful when the sampling and application are performed using precision agriculture technologies such as GPS, geographic information systems and variable-rate applicators. However, conventional application technology can also be effective (rates can be simply varied by adjusting the travel speed of the applicator.)

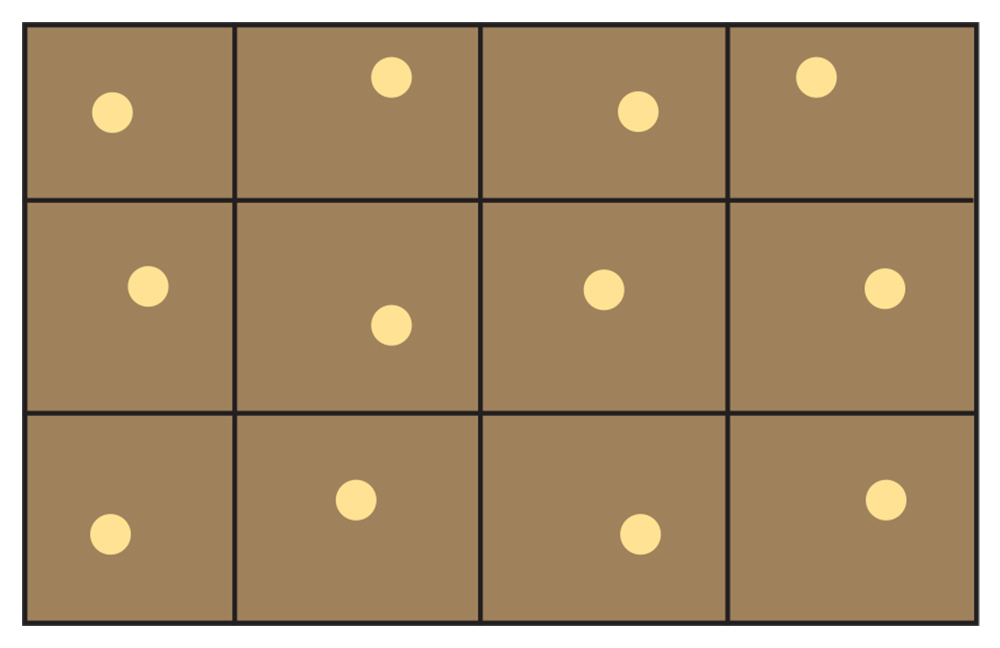

The general recommendation is for 2.5- to 5-acre grid sampling, especially for fields that have received variable manure and fertilizer rates. In some areas, one-acre grids are sampled. The suggested sampling procedure is called unaligned because in order to get a better picture of the field as a whole, grid points should not follow a straight line because you may unknowingly pick up a past applicator malfunction. Grid points can be designed with the use of precision agriculture software packages or by ensuring that sampling points are taken by moving a few feet off the regular grid in random directions (Figure 21.5). Grid sampling still requires 10–15 individual cores to be taken within about a 30-foot area around each grid point. Sampling units within fields may also be defined by soil type (from soil survey maps) and landscape position.

Grid soil testing may not be needed every time you sample the field—it is an expensive and time-consuming effort—but it is recommended to evaluate site-specific nutrient levels in larger fields at least once in a rotation, each time lime may be needed, or every five to eight years. Sometimes, sampling is done based on mapping units from a soil survey, but in many cases the fertility patterns don’t follow the soil maps. It is better to use grids first and then assess whether mapped soil zones can be used in the future.

Testing High Tunnel Soils

Growing vegetables in high tunnels has become popular as a way of improving crop quality and yield, and extending the growing season. These non-permanent structures provide superior growing conditions compared to the field by offering protection from low temperature, high temperature (with shading added and vents open) and rainfall, as well as the ability to optimize soil moisture and nutrients. Tunnels vary in size but typically are 20–30 feet wide, 100–200 feet long, with a quonset or gothic shape peaking at 10–15 feet. They are covered in greenhouse plastic and either passively or mechanically heated and vented. Drip irrigation is the standard, but surface mulches vary widely. Conventional growers may use synthetic rooting media such as rock wool, peat-lite mixes or other materials suitable for container culture. Organic growers must grow crops in the soil, so tunnels are usually placed over high-quality field soil, significantly amended to achieve the fertility levels needed to realize the high yield potential in tunnels. Tunnel tomatoes are frequently grafted onto greenhouse tomato rootstock to avoid soilborne diseases and to enhance plant vigor.

With a longer growing season, good cultural practices, pest management and sufficient nutrients, tomatoes can yield many times what is achievable outdoors, reaching the equivalent of 60–80 tons per acre. The amount of nutrients needed by such large yields is impressive: equivalent to 200–300 pounds of N, 300–400 pounds of phosphate (P2O5) and 700–900 pounds of potash (K2O) per acre. Many vegetable farmers follow their summer crops (most commonly tomatoes) with greens such as spinach, kale, lettuce and mustards, which allows for harvest of fresh greens throughout the cold winter months and straight through the spring until the subsequent summer crop is planted. Because of the high nutrient levels that are needed in tunnels, fertilizer recommendations based on routine "field soil tests" (using extracts to estimate availability of reserve nutrients) must be adjusted upwards. In addition, because transplants are expected to start growing immediately after being set in the tunnels, and because rainfall does not leach salts from the soil, a "potting soil test" such as the saturated media extract is also useful. That test measures water-soluble nutrient levels (immediately available nutrients), including nitrate-N and ammonium-N, as well as salinity (total salt) levels.

Nutrient Recommendations without Soil Analyses

As much as soil and tissue testing is now routine in countries with advanced agriculture, there are many places where soil testing and tissue analysis are either too expensive or logistically challenging. Looking at leaf discoloration patterns can be a good diagnostic approach for many crop deficiencies (see the discussion on nutrient deficiency symptoms in Chapter 23), but symptoms generally are apparent only when the nutrient is already severely deficient. A simple approach for nitrogen is the use of leaf color charts (available in printed format or as a mobile app; Figure 21.6), which are in use for rice, wheat and corn.

The remaining option without soil testing is to estimate fertilizer needs based on crop removal as we discussed in the “buildup and maintenance approach.” With this, the yield is multiplied by a crop nutrient removal factor to derive a recommendation and to prevent long-term depletion. In many other cases, farmers with limited access to credit or other resources simply apply what they can afford, which is often below the optimum amount.

Chapter 21 Summary

Routine soil tests for acidity and nutrient availability provide extremely valuable information for managing soil fertility. Soil test results provide a way to make rational decisions about applications of fertilizers and various amendments such as lime, manures and composts. This is the way to find out if a soil is too acid and, if it is, how much liming material will be needed to raise it to the pH range desired for the crops you grow (occasionally acidic material is applied to reduce pH). Testing soils on a regular basis, at least once every three years, should be part of the farm management system on all farms that grow crops. This allows you to follow changes that occur in your fields and may indicate an early warning of some action that needs to be taken.

Use a soil test laboratory that utilizes procedures shown to be appropriate for your region and state. Keep in mind that soil tests are not 100% perfect. Recommendations indicate the probability of improving crop nutrition: whether there is a high, medium or low probability of increasing crop yield or quality by adding a particular fertilizer. But while soil testing isn’t perfect, it’s one of the basic tools we have to guide decisions on the need to use fertilizers and amendments. With nitrogen, crop availability and fertilizer recommendations should be approached in a timely manner. Soil or tissue tests need to be done right before the major crop uptake phase, and models and sensors can be used to monitor the fields. Since nitrogen is a highly dynamic nutrient that is strongly impacted by weather events, new data-driven technologies offer great opportunities. When soil health practices like organic matter additions, reduced tillage, cover cropping and better rotations are implemented, they also change how N processes interact with weather, and the complexity of the system increases. Therefore, true 4R-Plus management requires better tools than simple static equations that are still the standard for crop N management promoted by most institutions.

Chapter 21 Sources

Allen, E.R., G.V. Johnson and L.G. Unruh. 1994. Current approaches to soil testing methods: Problems and solutions. In Soil Testing: Prospects for Improving Nutrient Recommendations, ed. J.L. Havlin et al., pp. 203–220. Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI.

Cornell Cooperative Extension. 2000. Cornell Recommendations for Integrated Field Crop Production. Cornell Cooperative Extension: Ithaca, NY.

Hanlon, E., ed. 1998. Procedures Used by State Soil Testing Laboratories in the Southern Region of the United States. Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin No. 190, Revision B. University of Florida: Immokalee, FL.

Herget, G.W. and E.J. Penas. 1993. New Nitrogen Recommendations for Corn. NebFacts NF 93–111. University of Nebraska Extension: Lincoln, NE.

Jokela, B., F. Magdoff, R. Bartlett, S. Bosworth and D. Ross. 1998. Nutrient Recommendations for Field Crops in Vermont. Brochure 1390. University of Vermont Extension: Burlington, VT.

Kopittke, P.M. and N.W. Menzies. 2007. A review of the use of the basic cation saturation ratio and the “ideal” soil. Soil Science Society of America Journal 71: 259–265.

Laboski, C.A.M., J.E. Sawyer, D.T. Walters, L.G. Bundy, R.G. Hoeft, G.W. Randall and T.W. Andraski. 2008. Evaluation of the Illinois Soil Nitrogen Test in the north central region of the United States. Agronomy Journal 100: 1070–1076.

McLean, E.O., R.C. Hartwig, D.J. Eckert and G.B. Triplett. 1983. Basic cation saturation ratios as a basis for fertilizing and liming agronomic crops. II. Field studies. Agronomy Journal 75: 635–639.

Penas, E.J. and R.A. Wiese. 1987. Fertilizer Suggestions for Soybeans. NebGuide G87-859-A. University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension: Lincoln, NE.

The Penn State Agronomy Guide. 2019–2020. Pennsylvania State University: University Station, PA.

Recommended Chemical Soil Test Procedures for the North Central Region. 1998. North Central Regional Research Publication No. 221 (revised). Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station SB1001: Columbia, MO.

Rehm, G. 1994. Soil Cation Ratios for Crop Production. North Central Regional Extension Publication 533. University of Minnesota Extension: St. Paul, MN.

Rehm, G., M. Schmitt and R. Munter. 1994. Fertilizer Recommendations for Agronomic Crops in Minnesota. BU-6240-E. University of Minnesota Extension: St. Paul, MN.

SARE. 2017. How to Conduct Research on Your Farm or Ranch. Available at www.sare.org/research.

Sela. S. and H.M. van Es. 2018. Dynamic tools unify fragmented 4Rs into an integrative nitrogen management approach. J Soil & Water Conserv. 73:107A–112A.

Chapter Appendix: The Basic Cation Saturation Ratio System

The basic cation ratio system was discussed earlier in this chapter. This appendix is intended to clarify the issues for those interested in soil chemistry and in a more in-depth look at the BCSR (or base ratio) system.

Background

The basic cation saturation ratio system attempts to balance the amount of Ca, Mg and K in soils according to certain ratios. The early concern of researchers was with the luxury consumption of K by alfalfa—that is, if K is present in very high levels, alfalfa will continue to take up much more K than it needs and, to a certain extent, it does so at the expense of Ca and Mg. When looking with the hindsight of today’s standards, the original experiments were neither well designed nor well interpreted and the system is therefore actually of little value. But its continued use perpetuates a basic misunderstanding of what CEC and base saturation are all about.

With very little data, Firman Bear and his coworkers decided that the “ideal” soil—that is, an “ideal” New Jersey soil—was one in which the CEC was 10 me/100g; the pH was 6.5; and the CEC was occupied by 20% H, 65% Ca, 10% Mg and 5% K. And the truth is, for most crops, that’s not a bad soil test. It would mean that it contains 2,600 pounds of Ca, 240 pounds of Mg and 390 pounds of K per acre to a 6-inch depth in forms that are available to plants. While there is nothing wrong with that particular ratio (although to call it “ideal” was a mistake), the main reason the soil test is a good one is that the CEC is 10 me/100g (the effective CEC—the CEC the soil actually has—is 8 me/100g) and the amounts of Ca, Mg and K are all sufficient.

Problems with the System

When the cations are in the ratios usually found in soils, there is nothing to be gained by trying to make them conform to an “ideal” and fairly narrow range. In addition to the practical problems and the increased fertilizer it frequently calls for above the amount that will increase yields or crop quality, there is another issue: The system is based on a faulty understanding of CEC and soil acids, as well as on a misunderstanding and misuse of the term percent base saturation (%BS). When it is defined, you usually see something like the following:

%BS = 100 x sum of exchangeable cations / CEC

= 100 x (Ca++ + Mg++ + K+ + Na+) / CEC

First off, what does CEC mean? It is the capacity of the soil to hold onto cations because of the presence of negative charges on the organic matter and clays, but also to exchange these cations for other cations. For example, a cation such as Mg, when added to soils in large quantities, can take the place of (that is, exchange for) a Ca or two K ions that were on the CEC. Thus, a cation held on the CEC can be removed relatively easily as another cation takes its place. But how is CEC estimated or determined? The only CEC that is of significance to a farmer is the one that the soil currently has. Once soils are much above pH 5.5 (and almost all agricultural soils are above this pH, making them moderately acid to neutral to alkaline), the entire CEC is occupied by Ca, Mg and K (as well as some Na and ammonium). There are essentially no truly exchangeable acids (hydrogen or aluminum) in these soils. This means that the actual CEC of the soils in this normal pH range is just the sum of the exchangeable bases. The CEC is therefore 100% saturated with bases when the pH is over 5.5 because there are no exchangeable acids. Are you still with us?

As we discussed earlier in the chapter, liming a soil creates new cation exchange sites as the pH increases (see the section “Cation Exchange Capacity Management”). Laboratories using the BCSR system either determine the CEC at a higher pH or use other methods to estimate the so-called exchangeable hydrogen, which, of course, is not really exchangeable. Originally, the amount of hydrogen that could be neutralized at pH 8.2 was used to estimate exchangeable hydrogen. But when your soil has a pH of 6.5, what does a CEC determined at pH 8.2 (or pH 7 or some other relatively high pH) mean to you? In other words, the percent base saturation determined in this way has no relevance whatsoever to the practical issues facing farmers as they manage the fertility of their soils. Why then even determine and report a percent base saturation and the percentages of the fictitious CEC (one higher than the soil actually has) occupied by Ca, Mg and K?