The depletion of the soil humus supply is apt to be a fundamental cause of lowered crop yields.

—J.L. Hills, C.H. Jones and C. Cutler, 1908

The amount of organic matter in any particular soil is the result of a wide variety of environmental, soil and agronomic influences. Some of these, such as climate and soil texture, are naturally occurring. Hans Jenny carried out pioneering work on the effect of natural influences on soil organic matter levels in the United States more than 70 years ago. But agricultural practices also influence soil organic matter levels. Tillage, crop rotation and manuring practices all can have profound effects on the amount of soil organic matter.

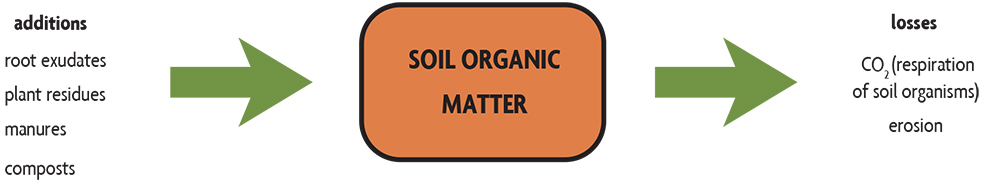

The amount of organic matter in a soil is the result of all the additions and losses of organic materials that have occurred over the years (Figure 3.1). In this chapter, we will look at why different soils have varying levels of organic matter. While we will be looking mainly at the total amount of organic matter, keep in mind that all three “types” of organic matter—the living, dead and very dead—serve critical roles, and the amount of each may be affected differently by natural factors and agricultural practices.

Anything that adds large amounts of organic residues to a soil may increase organic matter. On the other hand, anything that causes soil organic matter to decompose more rapidly or to be lost through erosion may deplete organic matter.

Storage of Organic Matter in Soil

Organic matter is protected in soils by:

- Formation of strong chemical bonds between organic matter and clay particles (and fine silt)

- Being inside small aggregates (physically protected)

- Conversion into stable substances such as humic materials that are resistant to biological decomposition

- Restricted drainage that reduces the activity of the decomposing organisms that need oxygen to function

- Stable char chemistry that is produced by incomplete burning

Large aggregates are made up of many smaller ones that are held together by sticky substances from roots, bacterial colonies and fungal hyphae. Organic matter in large aggregates—but outside of the small aggregates that make up the larger ones—and freely occurring particulate organic matter (the “dead”) are available for soil organisms to use. However, poor aeration resulting from restricted drainage because of a dense subsurface layer, compaction or being at the bottom of a slope or wetland area may cause a low rate of use of the organic matter. So the organic matter needs to be in a favorable chemical form and physical location for organisms to use it; plus, the environmental conditions in the soil—adequate moisture and aeration—need to be sufficient for most soil organisms to use the residues and thrive.

If additions are greater than losses, organic matter increases, which happens naturally when soils are formed over many years. When additions are less than losses, there is a depletion of soil organic matter, which generally happens when soils are put into crop production. When the system is in balance and additions equal losses, the quantity of soil organic matter doesn’t change over the years.

Natural Factors

Temperature

In the United States, it is easy to see how temperature affects soil organic matter levels. Traveling from north to south, higher average temperatures lead to less soil organic matter. As the climate gets warmer, two things tend to happen (as long as rainfall is sufficient): More vegetation is produced because the growing season is longer, and the rate of decomposition of organic materials in soils increases because soil organisms work more rapidly and are active for longer periods of the year at higher temperatures. Faster decomposition with warmer temperatures becomes the dominant influence determining soil organic matter levels. In the arctic and alpine regions there is not a lot of organic matter added to soils each year because of the very short season during which plants can grow. But arctic soils have high levels of organic matter because of the extremely slow decomposition rate caused by cold (and freezing) temperatures. However, with the Arctic’s temperature increasing and with the thawing of frozen soils, organic matter can be rapidly lost as microorganisms use it to live and give off CO2 during their respiration. Another greenhouse gas trapped in these soils, methane (CH4), is also being lost to the atmosphere. Thereby, the warming of the arctic and alpine regions is especially worrisome.

Rainfall

Soils in arid climates usually have low amounts of organic matter. In a very dry climate, such as a desert, there is little growth of vegetation. Decomposition is also low because of low amounts of organic inputs and low microorganism activity when the soil is dry. When it finally rains, a very rapid burst of decomposition of soil organic matter occurs. Soil organic matter levels generally increase as average annual precipitation increases. With more rainfall, more water is available to plants, and more plant growth results. As rainfall increases, more residues return to the soil from grasses or trees. At the same time, soils in high rainfall areas may have less organic matter decomposition than well-aerated soils. Decomposition is slowed by restricted aeration.

Soil Texture

Fine-textured soils, containing high percentages of clay and silt, tend to have naturally higher amounts of soil organic matter than coarse-textured sands or sandy loams. The organic matter content of sands may be less than 1%; loams may have 2% to 3%, and clays from 4% to more than 5%. The strong chemical bonds that develop between organic matter and clay and fine silt protect organic molecules from attack and decomposition by microorganisms and their enzymes. Also, clay and fine silt combine with organic matter to form very small aggregates that in turn protect the organic matter inside from organisms and their enzymes. In addition, fine-textured soils tend to have smaller pores and less oxygen than coarser soils. This also limits decomposition rates, one of the reasons that organic matter levels in fine-textured soils are higher than in sands and loams.

Soil Drainage and Position in the Landscape

Decomposition of organic matter occurs more slowly in poorly aerated soils. In addition, some major plant compounds such as lignin will not decompose at all in anaerobic environments. For this reason, organic matter tends to accumulate in wet soil environments. When conditions are extremely wet or swampy for a very long period of time, organic (peat or muck) soils develop, with organic matter contents of more than 20%. When these soils are artificially drained for agricultural or other uses, the soil organic matter will decompose rapidly. When this happens, the elevation of the soil surface actually decreases. Homeowners on organic soils in Florida normally sink the corner posts of their houses below the organic level to provide stability. Originally level with the ground, some of those homes now perch on posts atop a soil surface that has decreased so dramatically that the owners can park their cars under their homes!

Soils in depressions at the bottom of hills or in floodplains receive runoff, sediments (including organic matter) and seepage from upslope, and tend to accumulate more organic matter than drier soils farther upslope. In contrast, soils on a steep slope or knoll will tend to have low amounts of organic matter because the topsoil is continually eroded.

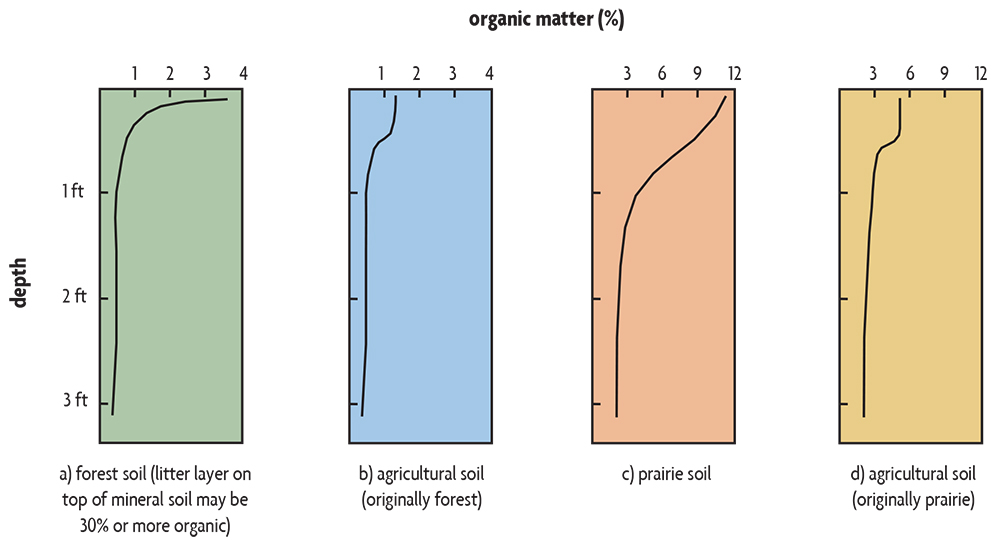

Type of Vegetation

The type of plants that grow on the soil as it forms can be an important source of natural variation in soil organic matter levels. Soils that form under grassland vegetation generally contain more and a deeper distribution of organic matter than soils that form under forest vegetation. This is probably a result of the deep and extensive root systems of grassland species (Figure 3.2). Their roots have high “turnover” rates as root die-off and decomposition constantly occur and as new roots are formed. Dry natural grasslands also frequently experience slow-burning fires from lightning strikes, which contribute biochar that is very resistant to degradation. The high levels of organic matter in soils that were once in grassland partly explain why these are now some of the most productive agricultural soils in the world. By contrast, in forests, litter accumulates on top of the soil, and surface organic layers commonly contain over 50% organic matter. However, the mineral layers immediate below typically contain less than 2% organic matter.

Acidic Soil Conditions

In general, soil organic matter decomposition is slower under acidic soil conditions than at a more neutral pH. In addition, acidic conditions, by inhibiting earthworm activity, encourage organic matter to accumulate at the soil surface, rather than to distribute throughout the soil layers.

Root Versus Aboveground Residue Contribution to Soil Organic Matter

Roots, already being well distributed and in intimate contact with the soil, tend to contribute a higher percentage of their weight to the more persistent organic matter (“dead” and “very dead”) than to aboveground residues. In addition, compared to aboveground plant parts, many crop roots have higher amounts of materials such as lignin that decompose relatively slowly. One experiment with oats found that only one-third of the surface residue remained after one year, while 42% of the root organic matter remained in the soil and was the main contributor to particulate organic matter. In another experiment, five months after spring incorporation of hairy vetch, 13% of the aboveground carbon remained in the soil, while close to 50% of the root-derived carbon was still present. Both experiments found that the root residue contributed much more to particulate organic matter (active, or “dead”) than did aboveground residue.

Human Influences

Erosion loss of topsoil that is rich in organic matter has dramatically reduced the total amount of organic matter stored in many soils after they were developed for agriculture. Crop production obviously suffers when part of the most fertile layer of the soil is removed. Erosion is a natural process and occurs on almost all soils. Some soils naturally erode more easily than others, and the problem is greater in some regions (like dry sparsely vegetated areas) than others. However, agricultural practices greatly accelerate erosion whether by water, wind or even tillage practices themselves (see Chapter 16). It is estimated that erosion in the United States is responsible for annual losses of about $1 billion in available nutrients and many times more in total soil nutrients.

Unless erosion is severe, a farmer may not even realize a problem exists. But that doesn’t mean that crop yields are unaffected. In fact, yields may decrease by 5–10% when only moderate erosion occurs. Yields may suffer a decrease of 10–20% or more with severe erosion. The results of a study of three Midwestern soils (referred to as Corwin, Miami and Morley), shown in Table 3.1, indicate that erosion greatly affects both organic matter levels and water-holding ability. Greater amounts of erosion decreased the organic matter content of these loamy and clayey soils. In addition, eroded soils stored less available water than minimally eroded soils. Organic matter also is lost from soils when organisms decompose more organic materials during the year than are added. This occurs as a result of practices that accelerate decomposition, such as intensive tillage and crop production systems that return low amounts of plant biomass, directly as crop residues or indirectly as manure. Even with residue retention, cash grain production systems export 55–60% of the organic matter off the farm. Therefore, much of the rapid loss of organic matter following the conversion of grasslands to agriculture has been attributed to large reductions in plant residue annually returned to soil, accelerated mineralization of organic matter because of plowing, and erosion.

Tillage Practices

Tillage practices influence both the amount of topsoil erosion and the rate of decomposition of organic matter. Conventional plowing and disking provide multiple short-term benefits: creating a smooth seedbed, stimulating nutrient release by enhancing organic matter decomposition, and helping control weeds. But by breaking down natural soil aggregates, intensive tillage destroys large, water-conducting channels and the soil is left in a physical condition that is highly susceptible to wind and water erosion.

| Table 3.1 Effects of Erosion on Soil Organic Matter and Water | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Erosion | Organic Matter (%) | Available Water Capacity (%) |

| Corwin | slight moderate severe | 3.03 2.51 1.86 | 12.9 9.8 6.6 |

| Miami | slight moderate severe | 1.89 1.64 1.51 | 16.6 11.5 4.8 |

| Morley | slight moderate severe | 1.91 1.76 1.6 | 7.4 6.2 3.6 |

| Source: Schertz et al. (1985) | |||

The more a soil is disturbed by tillage practices, the greater the potential breakdown of organic matter by soil organisms. This happens because organic matter held within aggregates becomes readily available to soil organisms when aggregates are broken down during tillage. Incorporating residues with a moldboard plow, breaking aggregates open and fluffing up the soil also allow microorganisms to work more rapidly. It’s something like opening up the air intake on a wood stove, which lets in more oxygen and causes the fire to burn hotter. Rapid loss of soil organic matter (and a burst of CO2 pumped into the atmosphere) occurs in the early years because of the high initial amount of active (“dead”) organic matter available to microorganisms. In Vermont, we found a 20% decrease in organic matter after five years of growing silage corn on a clay soil that had previously been in sod for decades. During the early years of agriculture in the United States, when colonists cleared the forests and planted crops in the East, and farmers later moved to the Midwest to plow the grasslands, soil organic matter decreased rapidly as the soils were literally mined of this valuable resource. In the Midwest, many soils lost 50% of their organic matter within 40 years of the onset of cropping. It was quickly recognized in the Northeast and Southeast that fertilizers and soil amendments were needed to maintain soil productivity. In the Midwest, the deep, rich soils of the tall-grass prairies were able to maintain their productivity for a long time despite accelerated loss of soil organic matter and significant amounts of erosion. The reason for this was their unusually high reserves of soil organic matter and nutrients at the time of conversion to cropland.

After much of the biologically active portion is lost, the rate of organic matter loss slows and what remains is mainly the already well-decomposed “passive” or “very dead” materials. With the current interest in reduced (“conservation”) tillage, growing row crops in the future should not have such a detrimental effect on soil organic matter. Conservation tillage practices leave more residues on the surface and cause less soil disturbance than conventional moldboard plows and disks. In fact, soil organic matter levels usually increase when no-till planters place seeds in a narrow band of disturbed soil, leaving the soil between planting rows undisturbed. Residues accumulate on the surface because the soil is not inverted by plowing. Earthworm populations increase because they are naturally adapted to feeding on plant residues left at the soil surface. They take some of the residues deeper into the soil and create channels that also help water infiltrate into the soil. The beneficial effects on soil organic matter levels from minimizing tillage are often observed quickly at the soil surface, but deeper changes are much slower to develop. In the upper Midwest there is conflicting evidence as to whether a long-term no-till approach results in greater accumulation of soil organic matter than a conventional tillage system when the full profile is considered. In contrast, significant increases in profile soil organic matter have been routinely observed under no-till in warmer locations.

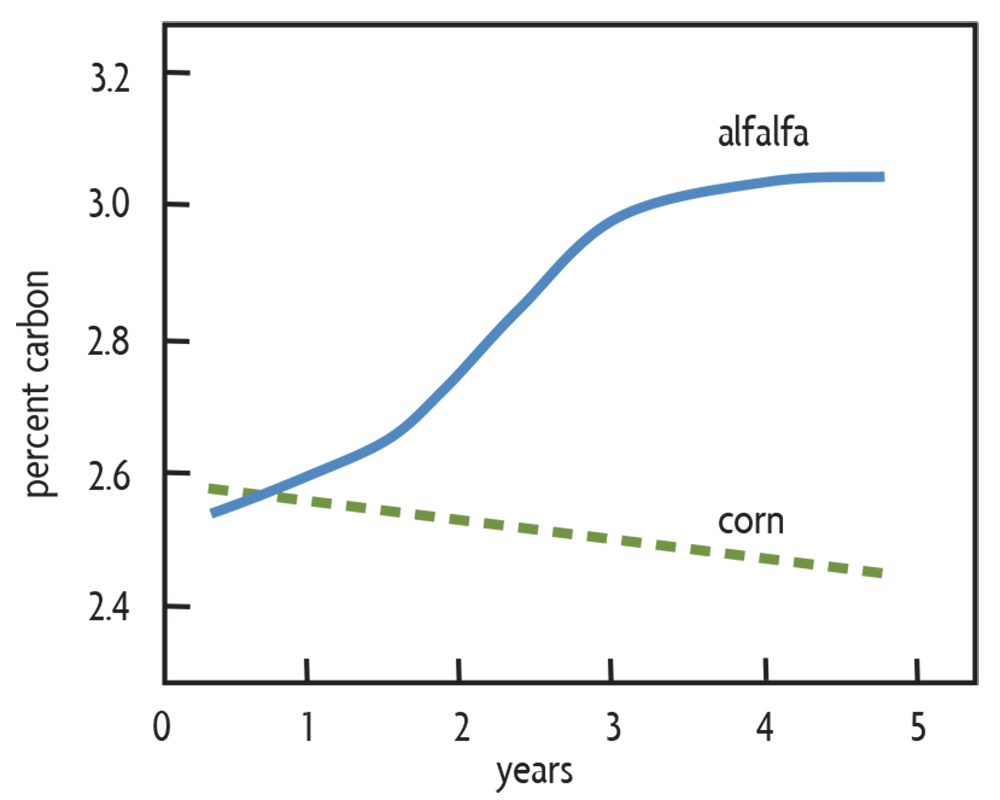

Crop Rotations and Cover Crops

Levels of soil organic matter may fluctuate during the different stages of a crop rotation. Soil organic matter may decrease, then increase, then decrease, and so forth. While annual row crops under conventional moldboard-plow cultivation usually result in decreased soil organic matter, perennial legumes, grasses and legume-grass forage crops tend to increase soil organic matter. The high amount of root production by hay and pasture crops, plus the lack of soil disturbance, causes organic matter to accumulate in the soil. This effect is seen in the comparison of organic matter increases when growing alfalfa compared to corn silage (Figure 3.3). In addition, different types of crops result in different quantities of residues being returned to the soil. When corn grain is harvested, more residues are left in the field than after soybean, wheat, potato or lettuce harvests. Harvesting the same crop in different ways leaves different amounts of residues. When corn grain is harvested, more residues remain in the field than when the entire plant is harvested for silage or when stover is used for purposes like bioenergy (Figure 3.4). You can therefore imagine a worst case scenario when a field has continuous annual row crop production, with grain and residue harvested from the field, and is combined with intensive tillage and no other organic additions like manure, compost or cover crops.

Soil erosion is greatly reduced and topsoil rich in organic matter is conserved when rotation crops, such as grass or legume hay, are grown year round. The permanent soil cover and extensive root systems of sod crops account for much of the reduction in erosion. Having sod crops as part of a rotation reduces the loss of topsoil, decreases decomposition of residues, and builds up organic matter by the extensive residue addition of plant roots.

Cover crops help protect soils from erosion during the part of the year between commercial crops when soils would otherwise be bare. In addition to protecting organic-matter-rich topsoil from erosion, cover crops may add significant amounts of organic materials to soil. But the actual amount added is determined by the type of cover crop (grass species versus legumes versus brassicas, etc.) and how much biomass accumulates before it is suppressed/killed in order to plant the following commercial crop.

Use of Synthetic Nitrogen Fertilizer

Fertilizing nutrient-deficient soils usually results in greater crop yields. A significant additional benefit is that it also achieves greater amounts of crop residue—roots, stems and leaves—resulting from larger and healthier plants. Most crop nutrients are applied in reasonable balance with crop uptake if the soil is regularly tested. However, nitrogen management is more challenging and includes more risk to farmers. Therefore, N fertilizer is commonly applied at much higher rates than needed by plants, sometimes by as much as 50%, which is costly and also creates environmental problems. (See Chapter 19 for a detailed discussion of nitrogen management.)

Use of Organic Amendments

An old practice that helps maintain or increase soil organic matter is to apply manures or other organic residues generated off the field. This happened naturally in older farming systems where crops and livestock were raised on the same farm, and much of the crop organic matter and nutrients was recycled as manure. A study in Vermont found that between 20 and 30 tons (wet weight, including straw or sawdust bedding) of dairy manure per acre were needed to maintain soil organic matter levels when silage corn was grown each year. This is equivalent to one or one and a half times the amount produced by a large Holstein cow over the whole year. Varying types of manure—bedded, liquid stored, digested, etc.—can produce very different effects on soil organic matter and nutrient availability. Manures differ in their initial composition and are affected by how they are stored and handled in the field: for example, surface applied or incorporated, which we discuss in Chapter 12.

Organic Matter Distribution Within Soil

With Depth

In general, more organic matter is present near the surface than deeper in the soil (see Figure 3.5). This is one of the main reasons that topsoils are more productive than subsoils that become exposed by erosion or mechanical removal of surface soil layers. Some of the plant residues that eventually become part of the soil organic matter are from the aboveground portion of plants. In most cases, plant roots are believed to contribute more to a soil’s organic matter than do the crop’s shoots and leaves. But when the plant dies or sheds leaves or branches, thus depositing residues on the surface, earthworms and insects help incorporate the residues on the surface deeper into the soil. The highest concentrations of organic matter, however, remain within 1 foot of the surface.

Litter layers that commonly develop on the surface of forest soils may have very high organic matter contents (Figure 3.5a). Plowing forest soils after removal of the trees incorporates the litter layers into the mineral soil. The incorporated litter decomposes rapidly, and an agricultural soil derived from a sandy forest soil in the North or a silt loam in the South would likely have a distribution of organic matter similar to that indicated in Figure 3.5b. Soils of the tall-grass prairies have a deeper distribution of organic matter (see Figure 3.5c). After cultivation of these soils for 50 years, far less organic matter remains (Figure 3.5d). In addition to accelerated organic matter loss caused by soil disturbance and aggregate breakdown, there is much less input of organic matter from crops that grow for three or four months during the year when compared to prairie vegetation.

Inside and Outside Aggregates

Organic matter occurs outside of aggregates as living roots, larger organisms or pieces of residue from a past harvest. Some organic matter is even more intimately associated with soil. Humic materials may be adsorbed onto clay and small silt particles, and small- to medium-size aggregates usually contain particles of organic matter. The organic matter inside very small aggregates is physically protected from decomposition because microorganisms and their enzymes can’t reach inside. This organic matter also attaches to mineral particles and thereby makes the small particles stick together better. The larger soil aggregates, composed of many smaller ones, are held together primarily by the hyphae of fungi with their sticky secretions, by sticky substances produced by other microorganisms, and by roots and their secretions. Microorganisms are also found in very small pores within larger aggregates, which can sometimes protect them from their larger predators: paramecium, amoeba and nematodes.

There is an interrelationship between the amount of fines (silt and clay) in a soil and the amount of organic matter needed to produce stable aggregates. The higher the clay and silt content, the more organic matter is needed to produce stable aggregates, because more is needed to occupy the surface sites on the minerals during the process of organic matter accumulation. In order to have more than half of the soil composed of water-stable aggregates, a soil with 50% clay may need twice as much organic matter as a soil with 10% clay.

Active Versus Passive Organic Matter

Most of the discussion in this chapter so far has been about the factors that control the quantity and location of total organic matter in soils. However, we should keep in mind that we are also interested in balancing the different types of organic matter in soils: the living, the dead (active) and the very dead (humus). As discussed earlier, a portion of soil organic matter is protected from decomposition because of its chemical composition, by being adsorbed on clay particles, or by being inside small aggregates that organisms can’t access (Table 3.2). We don’t want just a lot of passive organic matter (humus) in soil, we also want a lot of active organic matter to provide nutrients and aggregating glues when it decomposes. It supplies food to keep a diverse population of organisms present. When forest or grassland soils were first cultivated, rapid organic matter decreases were almost entirely due to a loss of the unprotected and therefore biologically active (“dead”) component. But although it decreases fastest when intensive tillage is used, the active portion also increases fastest when soil building practices such as reduced tillage, improved rotations, cover crops, and applying manures and composts are used to increase soil organic matter.

| Table 3.2 Location and Type of Soil Organic Matter | |

|---|---|

| Type | Location |

| Living | Roots and soil organisms live in spaces between medium to large aggregates and inside large aggregates |

| Active (dead) | Fresh and partially decomposed residue in spaces between medium to large aggregates and inside large aggregates |

| Passive (very dead) | a) Molecules and fragments of dead microorganisms tightly held on clay and silt particles; b) particles of organic residue inside very small (micro) aggregates; c) organic compounds that by their composition are difficult for organisms to use. |

Amounts of Living Organic Matter

In Chapter 4, we discuss the various types of organisms that live in soils. The weight of fungi present in forest soils is much greater than the weight of bacteria. In grasslands, however, there are about equal weights of the two. In agricultural soils that are routinely tilled, the weight of fungi is less than the weight of bacteria. The loss of surface residues with tillage lowers the number of surface-feeding organisms. And as soils become more compact, larger pores are eliminated first. To give some perspective, a soil pore that is 1/25 of an inch (1 millimeter) is considered large. These are the pores in which soil animals, such as earthworms and beetles, live and function, so the number of such organisms in compacted soils decreases. Plant root tips are generally about 0.1 millimeter (1/250 of an inch) in diameter. Very compacted soils that lost pores greater than that size have serious rooting problems. The elimination of smaller pores and the loss of some of the network of small pores with even more compaction is a problem for even small soil organisms.

The total amounts (weights) of living organisms vary in different cropping systems. In general, soil organisms are more abundant and diverse in systems with complex rotations that return more diverse crop residues and that use other organic materials such as cover crops, animal manures and composts. Leaves and grass clippings may be an important source of organic residues for gardeners. When crops are rotated regularly, fewer parasite, disease, weed and insect problems occur than when the same crop is grown year after year.

On the other hand, frequent cultivation reduces the populations of many soil organisms because their food supplies are depleted by decomposition of organic matter. Compaction from heavy equipment also causes harmful biological effects in soils. It decreases the number of medium to large pores, which reduces the volume of soil available for air, water and populations of organisms, such as mites and springtails, which need the large spaces in which to live.

How Much Organic Matter Is Enough?

We already mentioned that soils with higher levels of fine silt and clay usually have higher levels of organic matter than those with a sandier texture. However, unlike plant nutrients or pH levels, there are few accepted guidelines for adequate organic matter content in particular agricultural soils. We do know some general guidelines. For example, 2% organic matter in a sandy soil is very good and difficult to reach, but in a clay soil 2% indicates a greatly depleted situation. The complexity of soil organic matter composition, including biological diversity of organisms, as well as the actual organic chemicals present, means that there is no simple interpretation for total soil organic matter tests. We also know that soils higher in silt and clay need more organic matter to produce sufficient water-stable aggregates to protect soil from erosion and compaction.

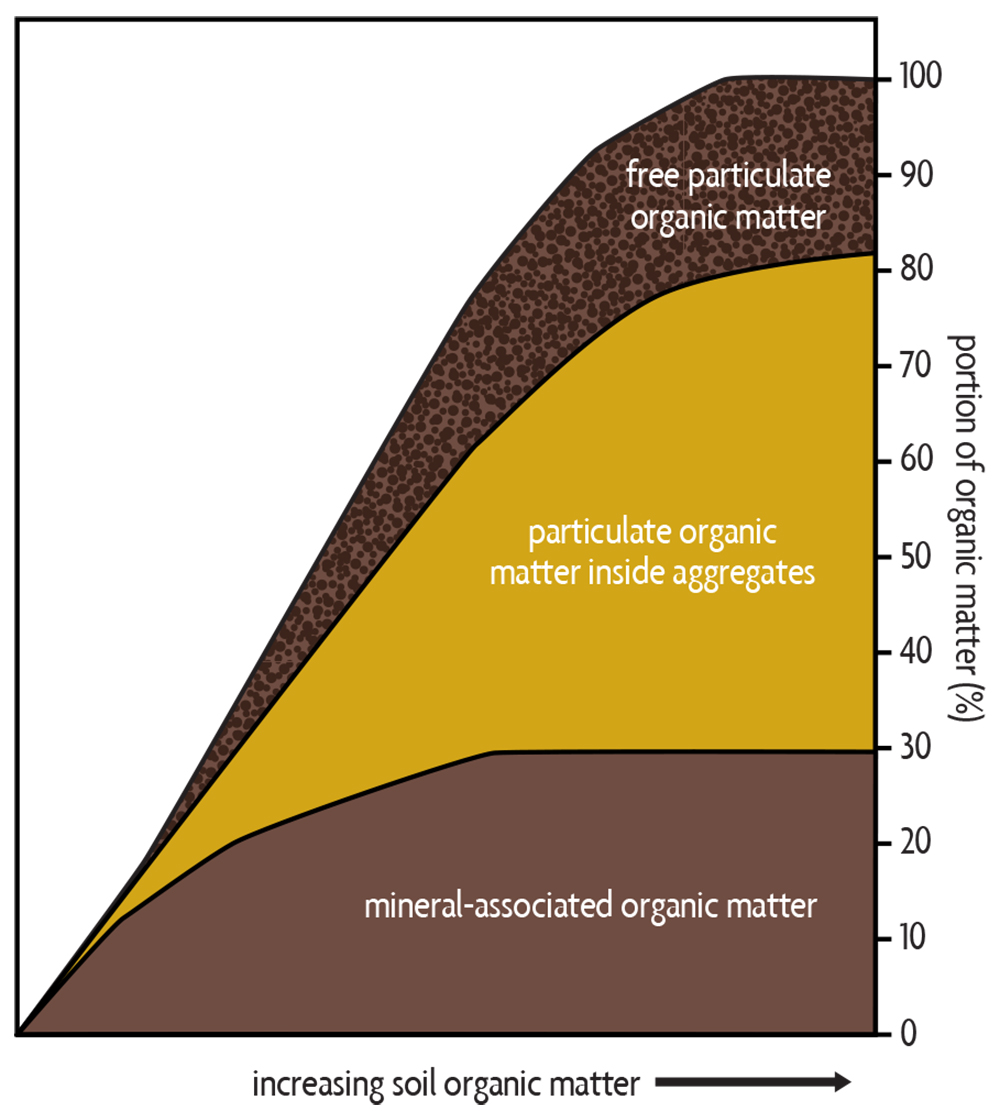

Some research has been conducted to determine the levels of organic matter where the fine soil mineral particles become saturated, having adsorbed as many organic compounds as possible. This provides some guidance where the soil is in terms of the current versus the potential organic matter level and whether or not the soil is at an upper equilibrium level. It also tells us whether the soil has the potential to store more organic matter as part of a carbon farming effort (carbon is 58% of organic matter). In this calculation, a soil with 20% silt and clay, for example, can store a maximum of 3.6% organic matter, while a soil with 80% silt and clay can hold 6.1% organic matter. This does not include the additional particulate organic matter that may be either subject to rapid decomposition (active) or protected from decomposition by soil organisms inside small (micro) aggregates (part of the passive organic matter). However, the clay content and type of clays present influence the amount of organic matter particles “stored” inside micro-aggregates. Organic matter accumulation takes place slowly and is difficult to detect in the short term by measurements of total soil organic matter. However, even if you do not greatly increase soil organic matter (and it might take years to know how much of an effect is occurring), improved management practices such as adding organic materials, creating better rotations and reducing tillage will help maintain the levels currently in the soil. And, perhaps more important, continuously adding a variety of residues results in plentiful supplies of “dead” organic matter—the relatively fresh particulate organic matter—that helps maintain soil health by providing food for soil organisms and promoting the formation of soil aggregates. We now have a soil test that tells you early on whether you are moving your organic matter levels in the right direction. It determines the amount of organic matter thought to be the active portion, is more sensitive to soil management than total organic matter and is an early indicator for soil health improvement (see Chapter 23).

The question will be raised, “How much organic matter should be assigned to the soil?” No general formula can be given. Soils vary widely in character and quality. Some can endure a measure of organic deprivation ... others cannot. On slopes, strongly erodible soils, or soils that have been eroded already, require more input than soils on level lands.

—Hans Jenny, 1980

Organic Matter and Cropping Systems

Natural (virgin) soils generally have much higher organic matter levels than agricultural soils. But there are also considerable differences among cropping systems that can be generalized as follows: In a cash grain operation, about 55–60% of the aboveground plant biomass is harvested as grain and sold off the farm, thereby returning less than half of the mass of the aboveground plant to the soil. The nutrients removed in the crops are replaced through fertilizers, but the carbon is not. On dairy farms, on the other hand, the crops are commonly fully harvested as a forage and fed to the animals, and then most of the plant biomass, including nutrients and carbon, is returned to the field as manure. While most dairy farms also grow their own feed grain, some import grain from other places, thereby accumulating additional organic matter and nutrients. When considering a typical conventional vegetable operation, as with cash grain, much of the plant biomass is harvested and sold off the farm, with limited return to the land. But a typical organic vegetable system imports a lot of compost or manure to maintain soil fertility and thereby applies quite a lot of organic matter to the soil. They are also more likely to grow a green manure crop to build fertility for the cash crop.

A recent New York study analyzed soil organic matter levels and soil health for such distinctive cropping systems and found considerable differences (Table 3.3). Soils that were used to grow annual grain crops (corn, soybeans, wheat) averaged 2.9% organic matter and conventional processing vegetables averaged 2.7%. Dairy fields averaged somewhat higher levels (3.4%) and mixed vegetables (mainly small organic farms) averaged 3.9% organic matter. The highest organic matter levels, however, were measured for pastures (4.5%), where much of the plant is recycled as manure and the soil is not tilled. As a result of the soil management and organic matter dynamics, the physical condition of the soil is also impacted. Aggregate stability, which is a good indicator of the physical health of the soil, is greater when the organic matter content is higher and the soil is not tilled (Table 3.3).

| Table 3.3. Organic Matter Levels and Percent Soil in Water-Stable Aggregates Associated with Different Cropping Systems in New York | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cropping System | Description | Organic Matter (%) | Aggregate Stability (%) |

| Conventional vegetable | Intensive tillage; mostly inorganic fertilizer; crop biomass removed | 2.7 | 27 |

| Annual grain | Range of tillage; mostly inorganic fertilizer; crop biomass mostly removed | 2.9 | 30 |

| Dairy | Rotation with perennial forage crops; mostly intensive tillage with corn silage; crop biomass removed but mostly recycled through manure | 3.4 | 36 |

| Mixed Vegetable (mostly organic) | Intensive tillage; green manure and cover crops; mostly organic fertilizer like compost | 3.9 | 44 |

| Pasture | No-till; perennial forage crop; crop biomass mostly recycled through manure | 4.5 | 70 |

The Dynamics of Raising and Maintaining Soil Organic Matter Levels

It is not easy to dramatically increase the organic matter content of soils or to maintain elevated levels once they are reached. In addition to using cropping systems that promote organic matter accumulation, it requires a sustained effort that includes a number of approaches that add organic materials to soils and minimize losses. It is especially difficult to raise the organic matter content of soils that are very well aerated, such as coarse sands, because of low potential for aggregation (which shelters organic matter from microbial attack) and limited protective bonds with fine minerals. Soil organic matter levels can be maintained with lower additions of organic residues in high-clay-content soils with restricted aeration than in coarse-textured soils because of the slower decomposition. Organic matter can be increased much more readily in soils that have become depleted of organic matter than in soils that already have a good amount of organic matter given their texture and drainage condition.

Starting Point

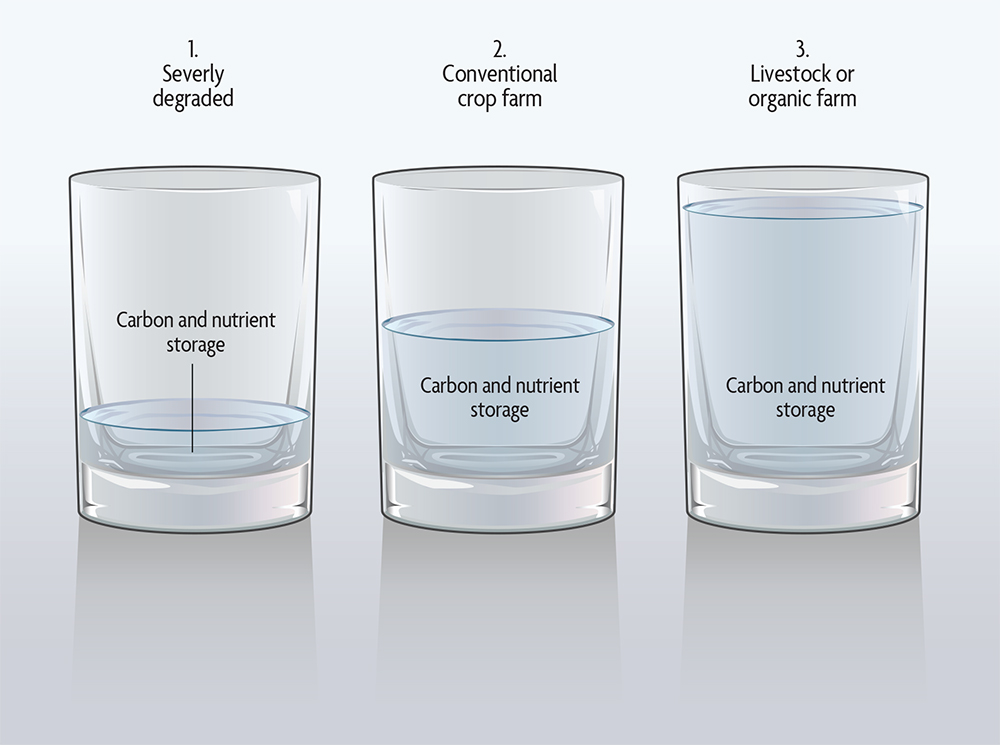

It is good to consider the soil’s current status when you build up organic matter in a soil. A useful analogy is the three glasses of water in Figure 3.6 that represent organic matter levels in different cropping systems. We are generalizing here, but some soils that are severely degraded (case 1, say from severe erosion or intensive tillage, etc.) have low organic matter levels (empty glass) and have the potential to increase and store much more. Another soil (case 3) may be in a cropping system that has for a long time been cycling much of the organic matter or has received a lot of external organic inputs as we discussed previously. Here the glass is nearly full and not much additional organic matter can be stored. In such cases we should focus on protecting the existing organic matter levels by minimizing losses. The in-between scenario (case 2) may be a conventional grain or vegetable farm where organic matter levels are suboptimal and can still be increased. In the context of carbon farming and raising overall soil organic matter levels, benefits will accrue more in cases 1 and 2 than in case 3, where the soil is already close to being saturated with organic matter. Moreover, if farms that fit case 3 are located near those that fit cases 1 or 2, there are potential gains from transferring the excess organic residues, like manure from a livestock farm to a farm growing only grain crops. Note: The amount of stored organic matter also depends on the soil type, especially clay content, and you may imagine a larger glass for a fine soil than a coarse soil, and the fullness of the glass is similarly proportional.

How Much Organic Material is Needed to Increase Soil Organic Matter by 1%?

To increase organic matter in your soil by 1%, let’s say from 2% to 3%, requires a lot of organic material to be added. This usually takes the form of plant roots, aboveground plant residues, manures and composts. But to give an idea of how much needs to be added for such a seemingly small increase (and is actually a LARGE increase), let’s do some calculations. A surface soil to 6 inches weighs about 2 million pounds. One percent organic matter in this soil would then weigh 20,000 pounds. But when organic material is added to soil, a large percentage is used as food by soil organisms, so a lot is lost during decomposition. If we assume that 80% is lost as soil organisms go about their lives and 20% eventually ends up as relatively stable soil organic matter, some 100,000 pounds (50 tons!) of organic materials (dry weight) would be needed. Because smaller amounts of residue are usually added to soils, large soil organic matter increases usually take time. In addition, soils with different amounts of clay and with different degrees of drainage have different abilities to protect organic materials from decomposition (see Table 3.4).

Adding Organic Matter

When you change practices on a soil depleted in organic matter, perhaps one that has been intensively row-cropped for years and has lost a lot of its original aggregation, organic matter will increase slowly, as diagrammed in Figure 3.7. At first, any free mineral surfaces that are available for forming bonds with organic matter will form organic-mineral bonds. Small aggregates will also form around particles of organic matter, such as the outer layer of dead soil microorganisms or fragments of relatively fresh residue. Then larger aggregates will form, made up of the smaller aggregates and held by a variety of means: frequently by mycorrhizal fungi and small roots. Once all possible mineral sites have been occupied by organic molecules and all of the small aggregates have been formed around organic matter particles, organic matter accumulates mainly as free particles, within the larger aggregates or completely unaffiliated with minerals. This is referred to as free particulate organic matter. After you have followed similar soil-building practices (for example, cover cropping or applying manures) for some years, the soil will come into equilibrium with your management and the total amount of soil organic matter will not change from year to year. In a sense, the soil is “saturated” with organic matter as long as your practices don’t change. All the sites that protect organic matter (chemical bonding sites on clays and physically protected sites inside small aggregates) are occupied, and only free particles of organic matter can accumulate. But because there is little protection for the free particles of organic matter, they tend to decompose relatively rapidly under normal (oxidized) conditions.

The reverse of what is depicted in Figure 3.7 occurs when management practices that deplete organic matter are used. First, free particles of organic matter are depleted, and then physically protected organic matter becomes available to decomposers as aggregates are broken down. What usually remains after many years of soil-depleting practices is organic matter that is tightly held by clay mineral particles and trapped inside very small (micro) aggregates.

Equilibrium Levels of Organic Matter

Assuming that the same management pattern has occurred for many years, a fairly simple model can be used to estimate the percent of organic matter in a soil when it reaches an equilibrium of gains and losses. This model allows us to see interesting trends that reflect the real world. To use the model you need to assume reasonable values for rates of addition of organic material and for soil organic matter decomposition rates in the soil. Without going through the details (see the appendix to this chapter for sample calculations), the estimated percent of organic matter in soils for various combinations of addition and decomposition rates indicates some dramatic differences (Table 3.4). It takes about 5,000 pounds of organic residues added annually to a sandy loam soil (with an estimated decomposition rate of 3% per year) to result eventually in a soil with 1.7% organic matter. On the other hand, 7,500 pounds of residues added annually to a well-drained, coarse-textured soil (with a soil organic matter mineralization, or decomposition, rate of 5% per year) are estimated to result after many years in only 1.5% soil organic matter.

| Table 3.4 Estimated Levels of Soil Organic Matter after Many Years with Various Rates of Decomposition (Mineralization) and Residue Additions* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine texture, poorly aerated <--> Coarse texture, well aerated | |||||||

| Annual organic material additions** | Added to soil if 20% remains after one year | Annual rate of organic matter decomposition | |||||

| 1% | 2% | 3% | 4% | 5% | |||

| ----pounds per acre per year---- | ---equilibrium % organic matter in soil --- | ||||||

| 2,500 5,000 7,500 10,000 | 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 | 2.5 5 7.5 10 | 1.3 2.5 3.8 5 | 0.8 1.7 2.5 3.3 | 0.6 1.3 1.9 2.5 | 0.5 1 1.5 2 | |

| *Assumes the upper 6 inches (15 centimeters) of soil weighs 2 million pounds. **10,000 pounds per acre addition is equivalent to 11,200 kilograms per hectare. | |||||||

Normally when organic matter is accumulating in soil it will increase at the rate of tens to hundreds of pounds per acre per year, but keep in mind that the weight of organic material in 6 inches of soil that contains 1% organic matter is 20,000 pounds. Thus, the small annual changes, along with the great variation you can find in a single field, means that it usually takes years to detect changes in the total amount of organic matter in a soil.

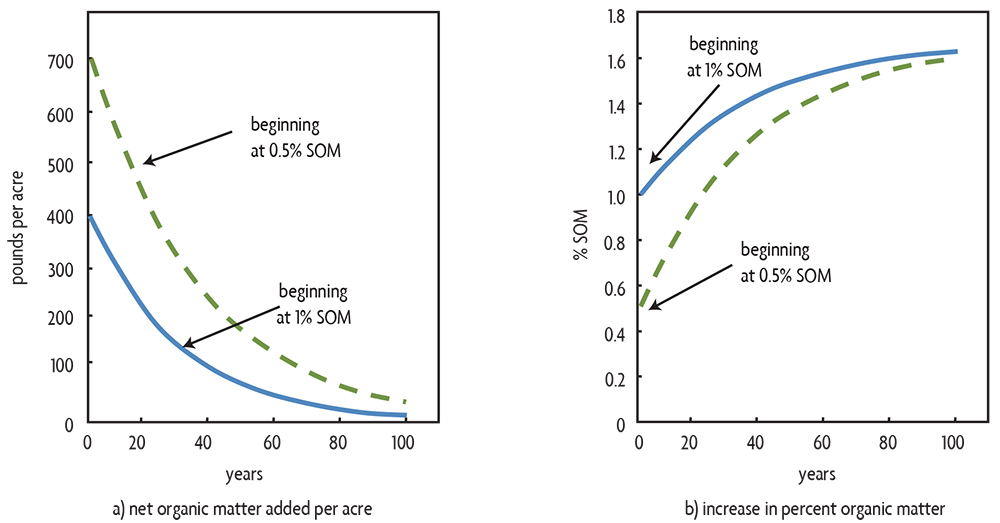

In addition to the final amount of organic matter in a soil, the same simple equation used to calculate the information in Table 3.4 can be used to estimate organic matter changes as they occur over a period of years or decades. Let’s take a more detailed look at the case where 5,000 pounds of residue is added per year with only 1,000 pounds remaining after one year. We assume that the residue remaining from the previous year behaves the same as the rest of the soil’s organic matter—in this case, decomposing at a rate of 3% per year. As we mentioned previously, with these assumptions, after many years a soil will end up having 1.7% organic matter at equilibrium. If a soil starts at 1% organic matter content, it will have an annual net gain of around 350 pounds of organic matter per acre in the first decade, decreasing to very small net gains after decades of following the same practices (Figure 3.8a). Thus, even though 5,000 pounds per acre are added each year, the net yearly gain decreases as the soil organic matter content reaches a steady state. If the soil was very depleted and the additions started when it was only at 0.5% organic matter content, a lot of organic material can accumulate in the early stages as it is bound to clay mineral surfaces and inside very small- to medium-size aggregates that form—preserving organic matter in forms that are not accessible to organisms to use. In this case, it is estimated that the net annual gain in the first decade might be over 600 pounds per acre (Figure 3.8a).

The soil organic matter content rises more quickly for the very depleted soil (starting at 0.5% organic matter) than for the soil with 1% organic matter content (Figure 3.8b), because so much more organic matter can be stored in organo-mineral complexes and inside very small and medium-size aggregates. This might be a scenario where a very degraded soil on a grain crop farm for the first time receives manure or compost, or starts to incorporate a cover or perennial crop. Once all the possible sites that can physically or chemically protect organic matter have done so, organic matter accumulates more slowly, mainly as free particulate (active) material.

Increasing Organic Matter Versus Managing Organic Matter Turnover

Increasing soil organic matter on depleted soils is important, but so is continually supplying new organic matter even on soils with good levels. It’s important to feed a diversity of soil organisms and provide replacement for older organic matter that is lost during the year. Organic matter decomposes in all soils, and we want it to do so. But that means we must continually manage the turnover. Practices to increase and maintain soil organic matter can be summarized as follows:

- Minimize soil disturbance to maintain soil structure with plentiful aggregation (reducing erosion, maintaining organic matter within aggregates);

- Keep the soil surface covered 1) with living plants if possible, planting cover crops when commercial crops are not growing, or 2) with a mulch consisting of crop residue (reducing erosion, adding organic matter);

- Use rotations with perennials and cover crops that increase biodiversity and add organic matter, including some crops with extensive root systems and plentiful aboveground residue after harvest;

- Add other organic materials from off the field when possible, such as composts, manures or other types of organic materials (uncontaminated with industrial or household chemicals).

Appendix

Calculations for Table 3.4 and Figure 3.8 Using a Simple Equilibrium Model

The amount of organic matter in soils is a result of the balance between the gains and losses of organic materials. Let’s use the abbreviation SOM as shorthand for soil organic matter. Then the change in soil organic matter during one year (the SOM change) can be represented as follows:

SOM change = (gains) – (losses) [equation 1]

If gains are greater than losses, organic matter accumulates and the SOM change is positive. When gains are less than losses, organic matter decreases and SOM change is negative. Remember that gains refer not to the amount of residues added to the soil each year but rather to the amount of residue added to the more resistant pool that remains at the end of the year. This is the fraction (F) of the fresh residues added that do not decompose during the year multiplied by the amount of fresh residues added (A), or gains = (F) x (A). For purposes of calculating the SOM percentage estimates in Table 3.3 we have assumed that 20% of annual residue additions remain at the end of the year in the form of slowly decomposing residue.

If you follow the same cropping and residue or manure addition pattern for a long time, a steady-state situation usually develops in which gains and losses are the same and SOM change = 0. Losses consist of the percentage of organic matter that’s mineralized, or decomposed, in a given year (let’s call that K) multiplied by the amount of organic matter (SOM) in the surface 6 inches of soil. Another way of writing that is losses = (K) x (SOM). The amount of organic matter that will remain in a soil under steady-state conditions can then be estimated as follows:

SOM change = 0 = (gains) – (K) x (SOM) [equation 2]

Because in steady-state situations gains = losses, then gains = (K) x (SOM), or

SOM = (gains) / (K) [equation 3]

A large increase in soil organic matter can occur when you supply very high rates of crop residues, manures and composts or grow cover crops on soils in which organic matter has a very low rate of decomposition (K). Under steady-state conditions, the effects of residue addition and the rate of mineralization can be calculated using equation 3 as follows.

If K = 3% and 2.5 tons of fresh residue are added annually, 20% of which remains as slowly degradable following one year, then the gains at the end of one year = (5,000 pounds per acre) x 0.2 = 1,000 pounds per acre.

Assuming that gains and losses are happening only in the surface 6 inches of soil, then the amount of SOM after many years when the soil is at equilibrium = (gains) / (K) = 1,000 pounds / 0.03 = 33,333 pounds of organic matter in an acre to 6 inches.

The percent SOM = 100 (33,000 pounds of organic matter / 2,000,000 pounds of soil).

The percent SOM = 1.7%.

Chapter 3 Sources

Angers, D.A. 1992. Changes in soil aggregation and organic carbon under corn and alfalfa. Soil Science Society of America Journal 56: 1244–1249.

Brady, N.C. and R.R. Weil. 2016. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed. Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Carter, M. 2002. Soil quality for sustainable land management: Organic matter and aggregation—Interactions that maintain soil functions. Agronomy Journal 94: 38–47.

Carter, V.G. and T. Dale. 1974. Topsoil and Civilization. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK.

Gale, W.J. and C.A. Cambardella. 2000. Carbon dynamics of surface residue–and root-derived organic matter under simulated no-till. Soil Science Society of America Journal 64: 190–195.

Hass, H.J., G.E.A. Evans and E.F. Miles. 1957. Nitrogen and Carbon Changes in Great Plains Soils as Influenced by Cropping and Soil Treatments. U.S. Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin No. 1164. U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC. (This is a reference for the large decrease in organic matter content of Midwest soils.)

Jenny, H. 1941. Factors of Soil Formation. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY. (Jenny’s early work on the natural factors influencing soil organic matter levels.)

Jenny, H. 1980. The Soil Resource. Springer-Verlag: New York, NY.

Khan, S.A., R.L. Mulvaney, T.R. Ellsworth and C.W. Boast. 2007. The myth of nitrogen fertilization for soil carbon sequestration. Journal of Environmental Quality 36: 1821–1832.

Magdoff, F. 2000. Building Soils for Better Crops, 1st ed. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE.

Magdoff, F. and J.F. Amadon. 1980. Yield trends and soil chemical changes resulting from N and manure application to continuous corn. Agronomy Journal 72: 161–164. (See this reference for further information on the studies in Vermont cited in this chapter.)

National Research Council. 1989. Alternative Agriculture. National Academy Press: Washington, DC.

Puget, P. and L.E. Drinkwater. 2001. Short-term dynamics of root- and shoot-derived carbon from a leguminous green manure. Soil Science Society of America Journal 65: 771–779.

Schertz, D.L., W.C. Moldenhauer, D.F. Franzmeier and H.R. Sinclair, Jr. 1985. Field evaluation of the effect of soil erosion on crop productivity. In Erosion and Soil Productivity: Proceedings of the National Symposium on Erosion and Soil Productivity, pp. 9–17. New Orleans, December 10–11, 1984. American Society of Agricultural Engineers, Publication 8–85: St. Joseph, MI.

Tate, R.L., III. 1987. Soil Organic Matter: Biological and Ecological Effects. John Wiley: New York, NY.

Wilhelm, W.W., J.M.F. Johnson, J.L. Hatfield, W.B. Voorhees and D.R. Linden. 2004. Crop and soil productivity response to corn residue removal: A literature review. Agronomy Journal 96: 1–17.

Six, J., R. T. Conant, E.A. Paul and K. Paustian. 2002. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and Soil 241: 155–176.