Recent Highlights from the Southern Region

- In 2020, Southern SARE launched a new program, called the Sustainable Agriculture Leadership Program, to enhance the resiliency and vivacity of historically underserved farmers and ranchers. The program provides sponsorship support for recipients to conduct education and training activities in their communities, and it provides them with ways to access the resources they need. To date, the program has reached 30 recipients with sponsorships totaling nearly $50,000.

- One of the hallmarks of the SARE program is to encourage a systems approach to sustainable agriculture, and Southern SARE continues to advance systems research through its Large Systems grants program. In 2020, the program funded a 9-year, $1.8 million project at Langston University in Oklahoma focused on sustainable meat goat production and marketing. This project is unique in that its research is driven by a consortium of 1890 land-grant institutions and farmers seeking to strengthen the goat industry across the Southern region. In addition, we awarded our first $1 million Systems Research grant in 2021 on regenerative agriculture, funded through the National Center for Appropriate Technology.

- What does “quality of life” mean for sustainable agriculture research? We provided a working document to offer some guidance to those social scientists seeking clarity on where quality of life fits into SARE’s three-legged stool of sustainability. Examples that help bring the quality of life perspective into the program include examining issues through the lens of social health (civic agriculture, regional processing, locavores, governance structures) as well as ethical health (animal welfare, human rights, food security, fair reimbursement for farmers and farm workers).

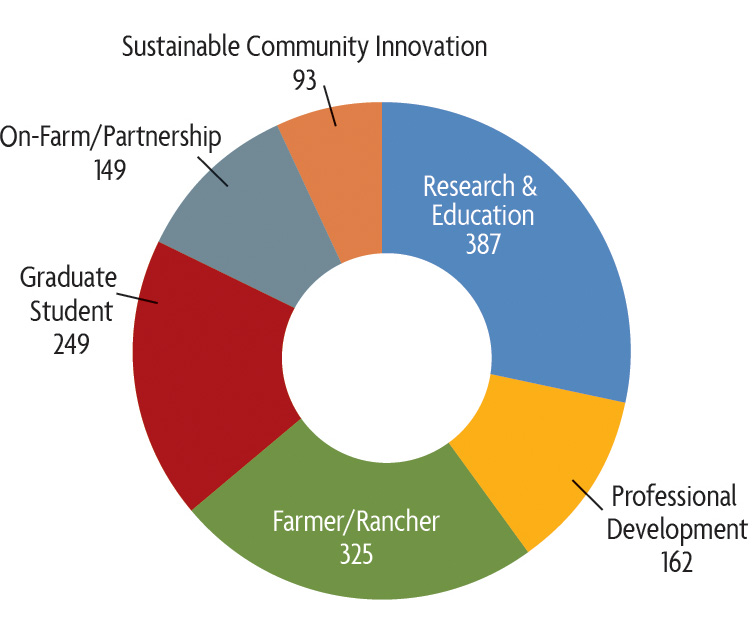

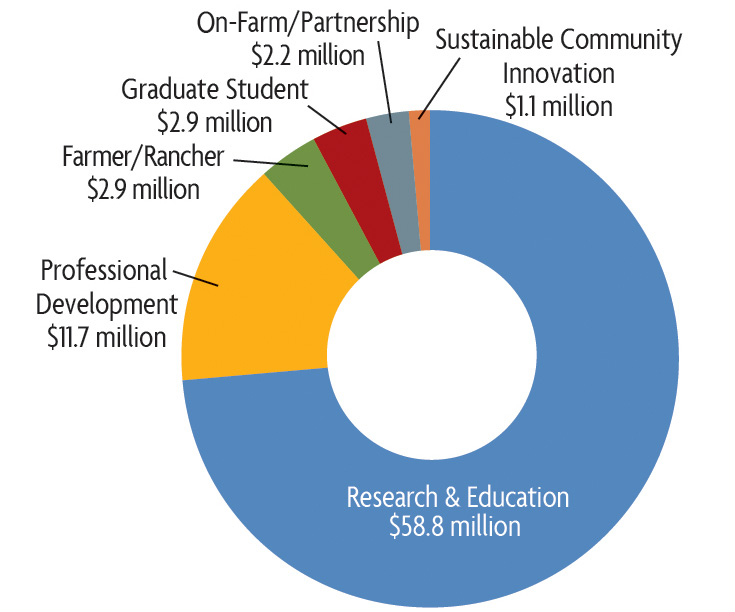

Total Grant Awards 1988-20211

1,365 Grants

$79.6 Million

Grant Proposals and Awards 2020-2021

| Grant type | Preproposals Received2 | Full Proposals Invited | Full Proposals Received | Proposals Funded | Funding Total |

| Research and Education | 287 | 118 | 104 | 41 | $9,081,641 |

| Professional Development Program | 72 | 36 | 30 | 16 | $1,220,258 |

| Farmer/Rancher | N/A | N/A | 84 | 17 | $217,867 |

| On-Farm Research/Partnership | N/A | N/A | 72 | 18 | $345,005 |

| Graduate Student | N/A | N/A | 202 | 35 | $539,536 |

1These totals exclude additional direct funding given each year to Cooperative Extension in every state to support state-level programming on sustainable agriculture.

2The use of a preproposal process varies by region. It serves to screen project ideas for the larger and more complex grant programs, and to reduce applicants' proposal preparation burden as well as the proposal review burden for SARE's volunteer reviewers.

Giving South Carolina Farmers Better Access to Wholesale Markets

The Challenge

More and more, large supermarkets, restaurants, food businesses and institutions are willing to offer local, sustainably raised products. Many small- and mid-scale farmers who are used to selling directly to consumers in small venues are interested in supplying these large buyers, but supplying crops to a distributor or supermarket is very different from selling at a farmers’ market; scaling up to wholesale requires a lot of changes in how farmers grow, harvest, package and deliver their products. A team of Extension and nonprofit educators in South Carolina found that the key knowledge gaps preventing farmers from scaling up their operations to meet strong local demand were best practices in food safety, postharvest handling, packing and business management.

In the long term, the project will result in a greater number of local farms that are able to sell products to wholesale market outlets, thereby increasing farmers’ market diversity and economic viability.”

Geoff Zehnder, Clemson University

The Actions Taken

To address these gaps, the team, led by Clemson University Professor Geoff Zehnder (now retired), organized a series of state-wide training events for Extension agents and other agricultural service providers. Over two years, the team developed a “wholesale success” training curriculum tailored to the needs of their stakeholders and delivered it through multi-day events. Along with classroom and field sessions, participants visited nearby produce processing facilities to learn about best practices. The lead instructor was Atina Diffley of FamilyFarmed, a leading expert on harvest and postharvest handling for wholesale markets.

The series focused on fruits and vegetables and covered topics such as proper pre/postharvest handling techniques; maintaining the cold chain; produce washing, grading and packing; developing relationships with buyers and identifying needs of wholesale buyers; best food safety practices; and scale-appropriate equipment and infrastructure for affordable processing.

The Impacts

The greatest impact of the project was the creation of a core group of Extension professionals in South Carolina who now have the tools and knowledge to help farmers tap wholesale markets, according to Zehnder. Some of the people trained through this project have gone on to hold their own events for Extension colleagues, which further expands the network. Other project impacts include:

- New knowledge: Of the 122 agricultural service providers who attended a training event, 81% reported that they gained new knowledge, skills and/or attitudes related to the topic. “We learned valuable tips on proper cleaning and storage of veggies,” said one. “The Wholesale Success manual has been very helpful as well.”

- New collaborations: The project team received one new grant to build on their work and established 12 new working collaborations.

- New training infrastructure: The team upgraded two Clemson facilities for vegetable postharvest handling so that they could be used for ongoing training and demonstration beyond the project’s scope.

Learn more: See the related SARE project ES17-137.

Texas Farmers and Scientists Explore Carbon Markets for Soil Health Practices

The Challenge

We know carbon can be taken out of the atmosphere and sequestered in the soil to help curb climate change. Practices like cover crops, crop rotations, reduced tillage, rotational grazing and agroforestry are among the most effective. Many kinds of financial programs exist to encourage farmers to adopt sustainable practices, and as the need to address climate change becomes increasingly urgent, more attention is turning to cost-effective programs that target carbon specifically. One approach is voluntary market trading, where agrifood businesses achieve carbon neutrality by paying farmers to sequester carbon. But for these programs to work, we need to know exactly how much carbon is sequestered by farming practices in the context of site-specific conditions such as climate and soil type. Also, to get farmers to participate, they need to learn about how these programs work and how they might fit into their decision-making.

While farmer participants were already knowledgeable about cover cropping and conservation tillage practices ... they were not familiar with the concept of potentially obtaining payments for carbon credits.”

Barbara Bellows, Tarleton State University

The Actions Taken

Supported by a SARE Research and Education grant, a multi-disciplinary team of scientists, service providers and farmers led by Barbara Bellows of Tarleton State University took on this challenge in the Southern Great Plains. Through a multi-faceted, three-year project, the team collected soil samples from 14 farms to determine the impact of farming practices, soil type and climate conditions on carbon sequestration and other soil health characteristics. They also interviewed farmers to learn what motivated them to use soil conservation practices, what discouraged them and whether carbon markets would influence their decision-making. The group engaged in extensive farmer outreach to share information about the many benefits of soil health practices, their potential for storing carbon, and current and future market opportunities for doing so.

The Impacts

The project’s biggest impact, according to Bellows, was that it shared useful information with area farmers about ecosystem service markets for both carbon sequestration and water conservation that they previously knew little about. Other impacts include:

- Practical knowledge: The team learned that soil type and climate influence carbon sequestration potential and other soil health characteristics. An economic and environmental analysis of participating farms found that using multiple conservation practices was better than simply adopting conservation tillage. These findings can help service providers make soil management recommendations that are better tailored to local conditions.

- Continuing research: Bellows and partners at Texas A&M received a $300,000 USDA NIFA grant to buy soil research equipment that will allow them to carry on this research more effectively.

- Impacts of incentives: The research team learned that farmers in the semi-arid areas of north-central Texas are hesitant to adopt cover crops unless provided with long-term incentives due to the irregularity of spring rainfall.

Learn more: See the related SARE project LS17-277.

Low-Cost Energy Solutions for Appalachian Greenhouse Growers

The Challenge

The demand for locally grown food is high in western North Carolina, and having a robust local food economy brings many benefits to both farmers and their communities. But many farms in the area have limited access to productive land because of the rugged Appalachian terrain, and the long, cold winters result in a short growing season. These factors result in smaller operations that have low on-farm income and limited resources, making it harder for them to meet local demand to the fullest. Any strategy that helps them cut costs, increase production and extend the growing season would be welcome news to farmers and to the communities that value them.

Our initial results show significant energy savings that will benefit resource-limited farmers.”

Ok-Youn Yu, Appalachian State University

The Actions Taken

One promising approach is to improve the energy efficiency of heated high tunnels and greenhouses, structures that extend the growing season into winter but carry a high energy cost. Supported by a 2018 On-Farm Research grant, Appalachian State University engineering professor Ok-Youn Yu worked with two area farms to install and test pilot systems that use alternative energy and improve heating efficiency. The systems were based on research Yu and colleagues are conducting at a university greenhouse in Boone, N.C. Before the project, one of the farms used propane to heat its greenhouse, and the other farm’s structure was unheated.

The pilot system uses solar power and a biochar kiln to heat a propylene glycol/water-based solution that is piped through greenhouse growing benches, along with tanks to store hot water. The kiln can use on-farm biomass such as wood, manure and food waste. One of its advantages is that it can use biomass that isn’t easily composted, and the resulting biochar can be applied as a soil amendment. The system includes a food dehydrator that can be powered during warm seasons when the greenhouse doesn’t need energy.

The Impacts

By successfully installing this alternative heating system at two farms, Yu and his team are creating new opportunities for Appalachian farmers to increase profitability, lower their carbon footprint and serve local markets. Impacts include:

- Reduced use of fossil fuels: One farm cut its propane use by more than half when it switched from using the fuel as a primary heat source to as a backup source only, while maintaining productivity.

- Lessons learned: The project team learned that the 40-gallon storage tank they installed at one of the farms to store energy wasn’t large enough to heat the entire greenhouse. Also, system efficiency is improved when growing benches are well insulated to prevent heat loss from the root zone heating system.

Learn more: See the related SARE project OS18-123.