Recent Highlights from the North Central Region

- Across the region, producers and organizations found themselves navigating online sales due to COVID-19, and North Central SARE made it a priority to help. We put together online resources and made quick supplemental funding available so that SARE state coordinators and regional organizations could help farmers and ranchers set up online marketing.

- Many SARE grantees have been tasked with converting in-person field days to virtual field days since March 2020. North Central SARE partnered with Maggie Norton, a farmer outreach coordinator for Practical Farmers of Iowa, to offer two webinars about hosting virtual field days. We shared the recorded webinars online and included equipment recommendations and costs.

- North Central SARE is working to encourage fuller participation and to build relationships with a diversity of producers in the region. Working alongside SARE state coordinators and 1994 institutions, we are providing mini-grants for food sovereignty projects at 14 of the twenty 1994 institutions in the region.

- Farmers Forums are events that give regional SARE grant recipients the chance to share information about sustainable agriculture practices at conferences. We are working with conference planners across the region to expand our Farmers Forums. Eventually, we hope to have SARE grantees presenting their work at existing conferences in each of our 12 states.

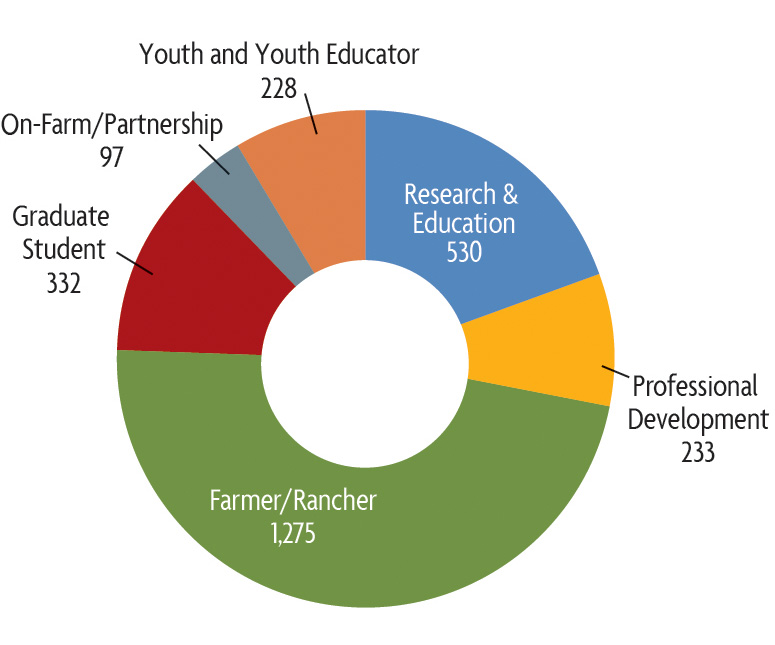

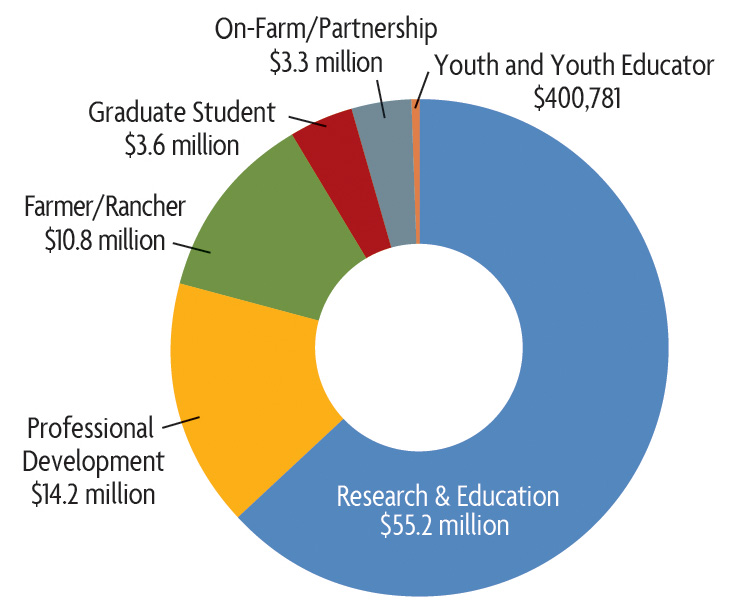

Total Grant Awards 1988-20211

2,695 Grants

$87.5 Million

Grant Proposals and Awards 2020-2021

| Grant type | Preproposals Received2 | Full Proposals Invited | Full Proposals Received | Proposals Funded | Funding Total |

| Research and Education | 299 | 66 | 64 | 28 | $6,675,364 |

| Professional Development Program | N/A | N/A | 45 | 22 | $1,830,933 |

| Farmer/Rancher | N/A | N/A | 205 | 113 | $1,418,542 |

| On-Farm Research/Partnership | N/A | N/A | 82 | 31 | $1,220,623 |

| Graduate Student | N/A | N/A | 106 | 46 | $654,028 |

1These totals exclude additional direct funding given each year to Cooperative Extension in every state to support state-level programming on sustainable agriculture.

2The use of a preproposal process varies by region. It serves to screen project ideas for the larger and more complex grant programs, and to reduce applicants' proposal preparation burden as well as the proposal review burden for SARE's volunteer reviewers.

Increasing Food Security in a Mohican Tribal Community

The Challenge

Like many rural communities, the Stockbridge-Munsee Community, a Mohican Indian tribe in north central Wisconsin, wants to increase its access to fresh produce but faces multiple barriers. For one, the tribe owns 500 acres of farmland that has become depleted of nutrients and organic matter after many years of improper management by previous tenants. Local gardeners and farmers lack knowledge of the soil management practices that improve fertility, such as taking and interpreting soil tests, making compost and using cover crops. Also, some community members are reluctant to grow produce because of the intensive labor required to control weeds. Food preservation and season extension are other areas where there’s an opportunity to improve food security, but also a lack of knowledge on how to do so.

“We had a number of people reach out wanting to grow vegetables for the first time or for the first time in a long time.”

Kellie Zahn, Stockbridge-Munsee Community Agriculture Agent

The Actions Taken

Funded by two SARE grants, Stockbridge-Munsee Community Agriculture Agent Kellie Zahn is working with local educators to give new and existing farmers hands-on training in many areas that she hopes will improve the tribe’s ability to grow fresh produce. Based at a community farm called “Keek-oche” in Mohican or “From the Earth” in English, Zahn and her collaborators have organized events and demonstrations on soil testing, crop rotation, cover crops, composting and intercropping with the traditional “Three Sisters” of corn, beans and squash.

They have made weed management a primary focus as well. Zahn has shown community members how to adopt effective tools such as flame weeding, landscape fabrics and mulches. Other demonstrations showed how to extend the growing season by using low tunnels and by starting seeds indoors with simple pots made of newspaper. Food preservation, composting, beekeeping and promoting beneficial insects were other topics they addressed.

They also collected data on crop yield from the demonstration farm and on sales at the local farmers’ market to help small-scale growers assess the profit potential of selling produce within the community.

The Impacts

The Stockbridge-Munsee Community’s food sovereignty committee is happy with the team’s progress and is eager to see it continue, Zahn reports. Specific impacts include:

- Sharing new information: The project team reached more than 200 farmers through workshops and online events. They also produced a series of fact sheets and videos throughout the project to supplement their events.

- Increased farmer knowledge: More than 50 farmers reported that they learned something new in the areas of soil health, weed management, vegetable production, beekeeping and indigenous farming techniques.

- Leveraged funding: The project team has received five new grants to continue their food security work in the community.

Learn more: See the related SARE projects ONC18-050 and LNC18-414.

North Dakota Farmers Lead the Way With Bale Grazing

The Challenge

When siblings Erin and Drew Gaugler, who grew up on a farm, decided to turn to agriculture full time as adults, they found themselves ranching on land in North Dakota that had been severely degraded from years of mismanagement by previous occupants. Farming and overgrazing had left the soil with low fertility and susceptible to wind and water erosion. The Gauglers began to rejuvenate the land with cover crops and intensive rotational grazing. They also became interested in bale grazing, or the practice of leaving hay bales in fields during the winter for livestock to graze. University research has shown that bale grazing can increase soil health and reduce winter feeding costs, but the Gauglers couldn’t find good examples of how to bale graze on a working ranch, giving them little guidance on how to move forward.

Bale grazing, like any other strategy or practice, can be implemented in many unique ways, which is important because each operation is different.”

Erin Gaugler, Gaugler Farm and Ranch

The Actions Taken

Supported by a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant, the Gauglers set up and monitored a system that involved planting multi-species cover crops and grazing them in the fall, then putting out bales for livestock to graze over the winter. Permanent and temporary fencing was used to rotate the animals and control their access to the hay, and bales were placed in areas that had especially low levels of organic matter. The Gauglers took soil samples and tracked body condition scores.

In 2020 the Gauglers received a second SARE grant to continue their evaluation of bale grazing and to integrate sheep into the system. A benefit of adding sheep is that manure is more evenly distributed across the field and soil compaction is limited. Also, cattle and sheep don’t share parasites, which helps break pest life cycles. Sheep are able to browse closer to manure deposits than cattle are, which can result in improved feeding efficiency.

While they used cover crops in conjunction with bale grazing during the first project, the Gauglers observed that bale grazing on established perennial fields was a more effective strategy to build soil health and to improve both forage production and economic sustainability.

The Impacts

While some of their work is ongoing, the Gauglers have achieved one of their primary goals: showing themselves and their neighbors that bale grazing is viable. “Folks in the local area have asked us several questions about what we are doing with the bales, and they wonder how it works,” said Erin. “Drew and I have noticed that a handful of those same people have begun to implement bale grazing on their own operation.” Other impacts include:

- Outreach to peers: Through tours, talks, podcasts, flyers and other outreach, the Gauglers reported sharing project information with 1,500 local farmers and 200 agriculture professionals.

- Farmer adoption: While the Gauglers report that 10 local farmers have changed or adopted a new practice after learning about their work with bale grazing, the impact across the region is harder to track.

Learn more: See the related SARE projects FNC20-1218 and FNC18-1123.

Bringing Fresh Foods to Illinois Schools and Institutions

The Challenge

While fresh, local foods have become very popular in grocery stores, restaurants and farmers’ markets, “institutionalized food is the forgotten part of the food revolution,” says Ann Swanson, the farm director at Hendrick House, a private business that offers housing, catering and dining hall services for University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The institutions that provide dining services for grade schools and higher education tend to favor pre-packaged, processed foods over fresh, homemade foods because they are cheaper to source and nutritional guidelines are easier to track. Also, food service employees often lack the skills or training to prepare fresh foods. To ensure the long-term survival of the Hendrick House Farm and to create new opportunities for other local farmers, Swanson set out to bring the local food revolution to her company and to schools in her community.

We hope to make a change in institutionalized food that will be ongoing beyond the scope of this grant.”

Ann Swanson, Hendrick House Farm

The Actions Taken

Supported by a three-year SARE Farmer/Rancher grant, Swanson launched a series of educational activities for multiple audiences, based out of Hendrick House’s kitchens and at its 10-acre farm, which includes a one-acre demonstration area. She created a guidebook and held workshops for food service staff on storage and preparation of fresh foods, and worked with chefs on how to plan for and procure local, seasonal produce.

Swanson also teamed up with area nonprofits and schools to bring youths to her demonstration farm so they could see where food comes from and learn how to make healthy food choices. She hosted a range of groups, including kindergarteners, middle and high schoolers, STEM classes and a group of at-risk boys. During the course of the project, her outreach grew to include the Illinois Master Gardeners and Parkland College, which held horticulture and culinary classes on the farm.

The Impacts

“This project has changed our company immensely over the last two years,” says Swanson, who also cites new partnerships with area schools and nonprofits as positive results. Specific impacts include:

- Sourcing from local farms: Every chef in the Hendrick House company is now using produce from its farm, whereas before the project only 30% were. Also, the company more than doubled the amount it spent on local food from outside farms, and it doubled the number of farms it bought produce from to 12.

- More institutions on board: The farm-fresh produce Hendrick House buys is now being served through other institutions it contracts with, including a community college, a medical center and a drug rehabilitation clinic.

- Ongoing youth education: The number of youth workshops held at the farm went from two in 2017 to 20 in 2019.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNC17-1101.