Insect pests, weeds and pathogens are a challenge to farmers everywhere, and they’re often symptoms of poor environmental quality, crop stress or excessive soil disturbance. Frequent soil disturbance and fragmented habitats for pest predators are of special concern to urban farmers. The hotter temperatures that are common in urban areas can also result in increased growth and spread of insect and weed pests. Therefore, pest management on an urban farm prioritizes a healthy growing environment for crops.

Managing pests on urban farms is similar in many ways to rural farms, only it’s done at a smaller scale. Producers rely on a mix of cultural, physical, biological and chemical practices.

The first step to sustainable pest management is routine scouting to monitor for emerging pest problems. Make it a priority to check your crops for pests at least once a week and record what you see in a field notebook. When scouting, randomly select your plants and examine them for signs of insects, stress or disease. Take pictures and videos of new or unknown pests; the images will be useful when getting help with correct identifications. Regular scouting will help you develop your knowledge of the types of pests visiting your crops and the time of year they’re present. From this you can create an action plan that best manages pests on your farm.

Here are a few tips to consider when scouting for pests on your urban farm, according to Cornell Cooperative Extension Urban Agriculture Specialist Sam Anderson:

- Set aside a regular time to scout crops for pests. This includes the upper and undersides of leaves, stems and soil under the plant.

- Familiarize yourself with the pest or disease. Learn how to identify pests, their life cycle and early warning signs of their presence.

- Before the season, develop an action plan for pests you expect to encounter. Ask yourself what strategies you will use to manage the pest. This type of information can help you get ahead of any potential infestations. For example, insecticidal soaps have low toxicity and are effective for managing spider mites early in the season.

Cultural Controls

The primary aim of cultural practices is to maintain healthy, porous soil where crops can access water and nutrients, and where pest populations remain relatively low. Inadequate access to water and nutrients, as well as other suboptimal growing conditions, will stress your crops and make them more vulnerable to pest attacks and weed competition. Common cultural practices include:

- Planting cover crops, which can smother weeds, support beneficial organisms and improve soil health

- Planning a diverse crop rotation to disrupt the life cycles and habitat requirements of pests

- Building soil structure and fertility with composts and amendments

- Following sanitation practices, such as cleaning tools after use and clearing out crop debris after harvest

- Using practices that improve crop competition, such as transplants and disease-resistant varieties, and water and nutrient applications that are targeted to your crops and not to weeds.

Biological Controls

Biological control most commonly involves enlisting the help of pest predators to keep insects, weeds and other pests in check. The cultural practices described above that promote soil health also represent a form of biological control because healthy soil fosters beneficial organisms like arthropods, fungi and bacteria that suppress pathogens and prey on both insect pests and weed seeds.

Also, consider including flowering plants in and around your farm to attract beneficial insects, including both predators and pollinators. You can order and release beneficial insects like predatory mites and lady beetles for short-term insect pest management as required. Growing pollen-producing plants like ornamental peppers can sustain beneficial insects for longer-term control. These strategies are also highly effective in enclosed growing systems like high tunnels.

Ornamental flowers (e.g., sunflowers) or herbs (e.g., lavender) are another option to keep soil covered and attract beneficial insects. They can also be sold, but bear in mind that the flowers are critical for biological control, so cut them selectively and plan rotations to ensure that plants in flower remain on your farm throughout as much of the growing season as possible.

Physical Controls

Common physical control tactics include the use of traps, barriers and cultivation. Traps, such as yellow sticky cards and baited pheromone traps, attract insects based on visual and chemical cues. Traps are effective in detecting and managing problem insects like thrips, fungus gnats and whiteflies, all of which are often problems in greenhouses and hoop houses. Physically removing infested crops is also effective at limiting the buildup of insects and pathogens.

Other physical controls include barriers, such as row covers and shade cloth, that prevent insects from getting to your crops. Natural and plastic mulches are an effective physical barrier against weeds. At the smaller scales typical of urban farms and market gardens, hand tools and walk-behind tractors are often more feasible for cultivation and weeding than the tractors and larger tools commonly found on larger rural farms.

Chemical Controls

Many urban producers use organic inputs to manage insect, weed and disease pests. Because urban farms and community gardens are in highly populated areas, the use of non-organic pesticides is generally discouraged. Like your rural counterparts, if you do consider the use of chemical controls, be sure to follow integrated pest management (IPM) principles. IPM is a knowledge-based approach that seeks to minimize pesticide harm to human health and the environment by using preventive, low-risk methods before resorting to higher-risk methods. IPM begins with the cultural, biological and physical practices described above to minimize the risk of pest damage. Some IPM-based tips:

- Learn about the most common pest problems for the crops you intend to grow.

- Begin by developing a working knowledge of the pests you have or expect to find on your farm, and monitor for them regularly.

- Consult with a local Cooperative Extension specialist to correctly identify pests so that you can apply the appropriate control strategies.

- Conduct weekly surveys for pests and record their numbers to determine whether they warrant management.

- Use your records to anticipate pests, and manage around them with appropriate strategies like changing your planting dates or using transplants.

- In every case, begin with strategies that are the least toxic and that have the lowest potential to disturb the environment.

To learn more about IPM, visit your regional IPM center’s website, where they provide resources such as IPM guidelines and field guides. Whole-farm pest management strategies are discussed in more depth in SARE’s bulletin, A Whole Farm Approach to Managing Pests.

Profile: Wood Chips for Weed Management

Virginia

FS18-308: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Locally Available Wood Chips for Weed Control

Weed management represents a major barrier to production for urban producers. Problematic weeds like crabgrass and pigweed compete with plants for nutrients, water and light, and can result in less productive crops. Patrick Johnson contends with weeds on a regular basis on his urban farm, NANIH (Neighborly Affiliations for Naturally Idealized Health) Farm and Garden, located in Sandston, Va.

Established in 2013, NANIH is an urban farm where Johnson’s philosophy is to grow foods naturally and free of pesticides. Johnson grows and markets organic produce like strawberries, cucumbers and okra at his local farmers market in Ashland, Va. In addition to produce, Johnson provides permaculture consulting services along with his team, Diversity Permaculture, on topics related to organic agriculture, permaculture and nonprofit management.

In 2018, Johnson used a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant to compare the ability of two types of mulch to suppress weeds on his urban farm. Johnson was interested in mulch because it was a low-cost approach to weed management that didn’t involve chemical inputs or excessive tillage, and he could source it locally. Mulch offered many potential benefits to the growing system, including improved soil structure as the mulch breaks down, reduced soil erosion and improved water retention.

As part of the project, Johnson set up a replicated, randomized complete block design experiment where he compared a blended hardwood mulch, a double shredded hardwood mulch and a control plot. He measured weed mass, water retention and okra production weekly over the course of the study. Although there was no difference between the two types of mulch, he did find that the mulched plots had significantly less weed pressure than the control plots. Mulched plots also retained more water and produced more okra yield on average than control plots without mulch. Some of the problem weeds Johnson found were crabgrass, pigweed and morningglory, among others. He regards the project as a success, concluding that locally available wood chips provide multiple benefits to the growing system.

Johnson was able to source his mulch from local arborists and power and landscape companies for free or at low cost. Since the project ended, Johnson has found that leaf litter debris works just as well as hardwood mulch at suppressing weeds and retaining water, but with the added benefit of being much lighter and easier to work with. “By recycling our locally available resources like leaf litter and hardwood mulch on the farm, we can help close the loop and rely less on off-farm inputs,” he says. As a result of the project, he engaged with more than 1,600 farmers by presenting at regional conferences, where he shared practices on weed management and organic production for urban farmers.

Profile: Partnerships for the Prevention of Pests in New York

New York

ONE19-327: Two-Spotted Spider Mite IPM for Urban Agriculture

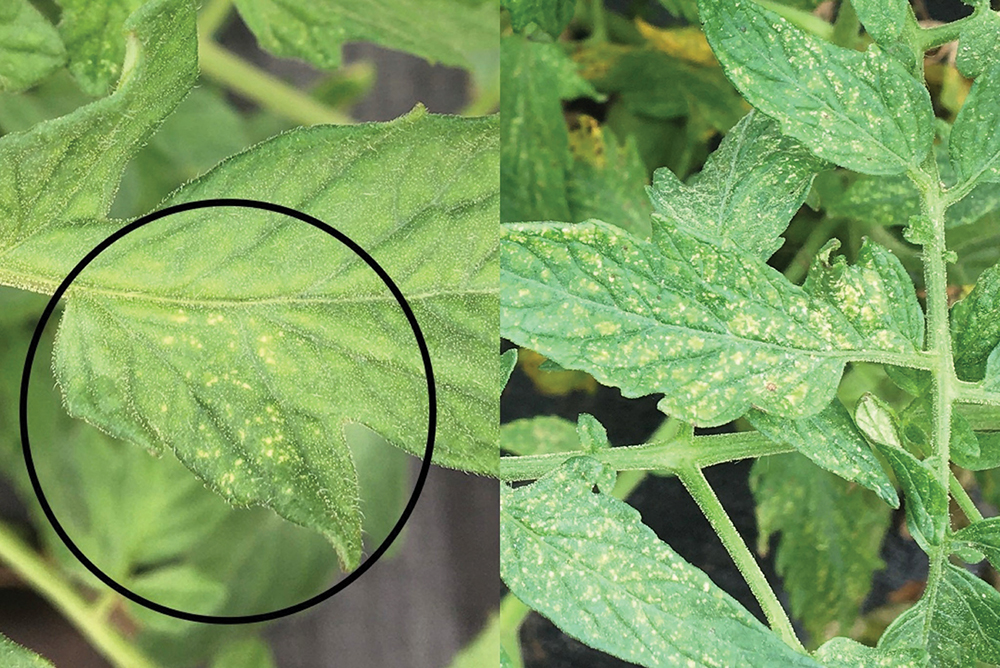

The two-spotted spider mite is a widespread and destructive pest that poses a threat in greenhouses and high tunnels across the country. These tiny arthropods thrive in hot, dry conditions and can explode in number when their natural predators are absent. Under the right conditions, a female spider mite can lay several hundred eggs over its four-week lifespan. A few of the telltale signs that spider mites are infesting your plants are tiny, yellow to brown spots and webbing on the undersides of plant leaves. When left unchecked, spider mite infestations almost always result in stunted or dead plants.

Cornell Cooperative Extension’s Sam Anderson, an urban agriculture specialist, is finding that two-spotted spider mite infestations are increasingly common on urban farms in New York, not just in greenhouses and high tunnels, but also in outdoor plantings of tomatoes, cucumbers and several other crops. Previous scouting found two-spotted spider mites on as much as 75% of urban farms visited in New York City. Anderson suggests that urban farms may be at a higher risk of spider mite infestations due to higher temperatures in cities compared to rural areas, as well as a lack of biodiversity and natural enemies to control them.

Using a 2019 SARE grant in partnership with Brooklyn Grange, Red Hook Farms and East New York Farms, Anderson and his collaborators set out to develop methods to more effectively scout for and manage two-spotted spider mites on urban farms. Their approach combined weekly scouting and the release of biological control species like predatory mites and gall midges. They chose bush beans as a potential sentry plant to detect early infestations of two-spotted spider mites. This is because bush beans develop spider mite damage symptoms earlier and the leaves of the plant are easier for farmers to examine compared to tomatoes. The research team established bush bean plantings at the end of tomato rows and tracked spider mite numbers over two seasons.

Anderson and his collaborators found that two-spotted spider mites typically arrived in early July, reached damaging levels in late July and August, and often caused complete crop loss of tomatoes by early September. The effectiveness of the biological controls they released were inconclusive. However, they noticed significantly fewer two-spotted spider mites on tomato plants bordered by marigolds or bush beans. They found high numbers of another mite predator, the minute pirate bug, in these areas and identified marigolds and bush beans as potential habitats to build up the population of this predator.

Although their biocontrol approaches were somewhat inconclusive, the rigorous scouting for two-spotted spider mites helped participating farmers develop an awareness of the pest. As a result of the project, information about two-spotted spider mites was shared with more than 300 farmers and agricultural educators through workshops, conferences, webinars and newsletters. By the end of the project, 50% of urban farmers in New York City could identify two-spotted spider mites in the field compared to 20% at the beginning of the project. Anderson regards this project as a success, saying, “We’ve definitely noticed that this project has garnered a lot of interest in learning how to scout for pests.”