Southern SARE Regional Highlights

- Connecting farmers and ag professionals in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to SARE grants and resources has always been a difficult task. Historically, the territories have received little funding from the SARE program compared to other states in the Southern region, with only 3.5% of total regional funding since 1988. Over the past several years, Southern SARE has expanded its outreach efforts and they are paying off. Collectively, grant funding across the territories has increased nearly 70% since 2022.

- On the Virgin Islands, results from a grant project on vetiver grass (EDS24-069) increased farm erosion control, and exploring lemongrass varieties (FS19-316) led to the development of a nascent lemongrass cooperative.

- Puerto Rico shares many of the agricultural problems that face the Virgin Islands, including ensuring long-term farmer sustainability. One particular Research and Education grant project (LS20-339) studied the viability of farm agritourism on the island. As a result of the work, 13 farmers in the mountainous region of Utuado were able to add various agritourism ventures to their farms.

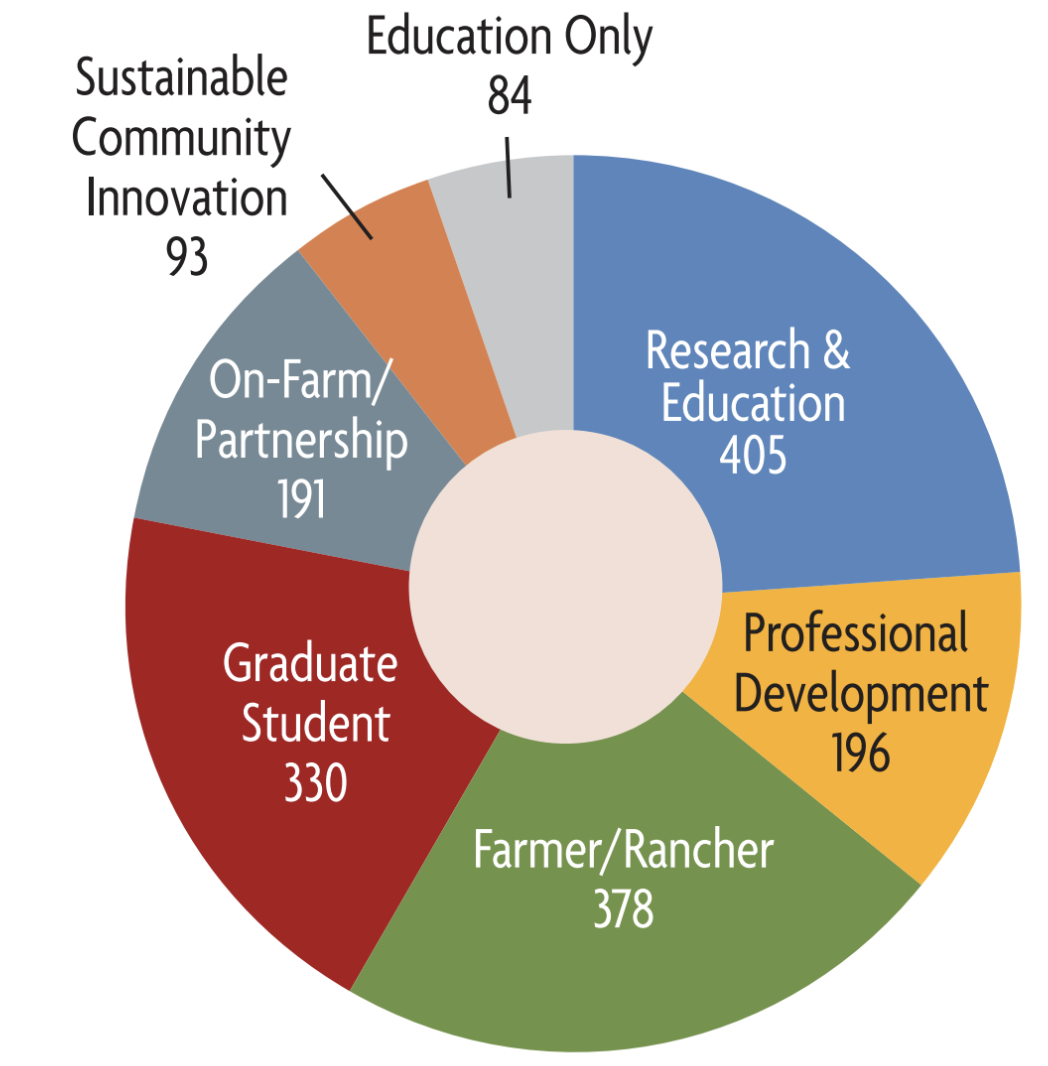

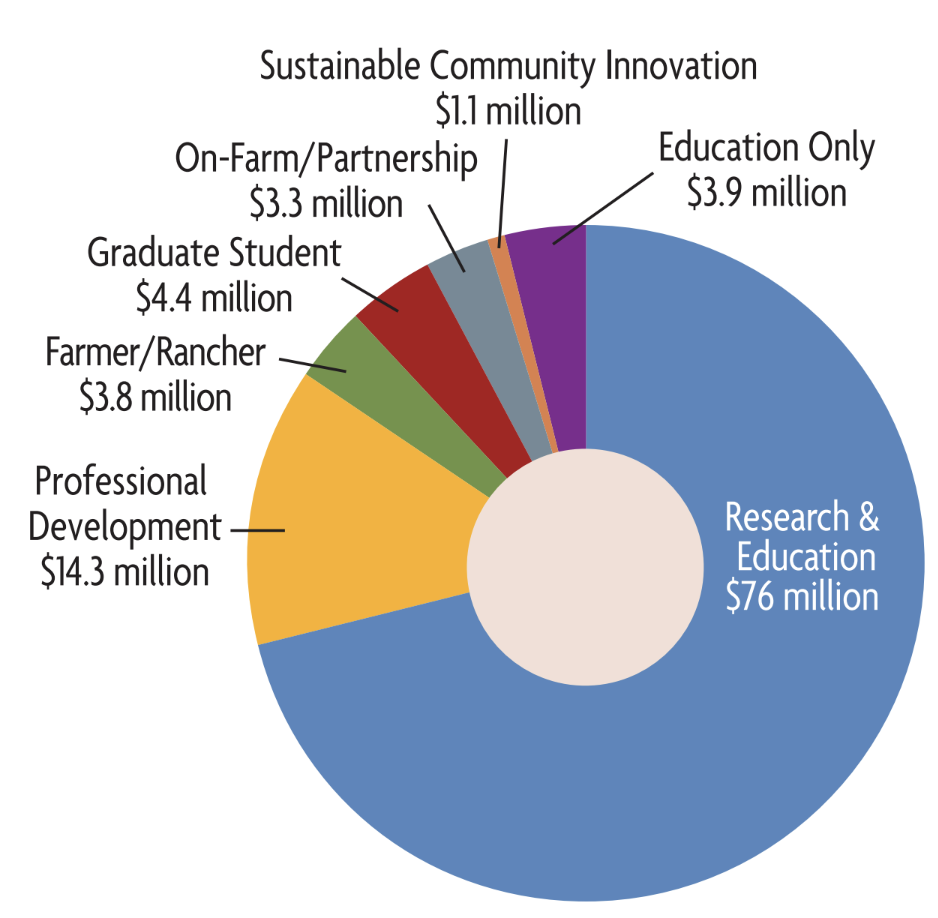

Total Grant Awards 1988-20251

1,677 GRANTS

$106.7 MILLION

Grant Proposals and Awards 2022-20251

| Grant type | Preproposals Received2 | Full Proposals Invited | Full Proposals Received | Proposals Funded | Funding Total |

| Research and Education | 207 | 81 | 75 | 23 | $9,037,331 |

| Professional Development Program | 90 | 52 | 48 | 18 | $1,406,678 |

| Farmer/Rancher | N/A | N/A | 140 | 31 | $570,440 |

| On-Farm Research/Partnership | N/A | N/A | 98 | 21 | $623,351 |

| Graduate Student | N/A | N/A | 409 | 38 | $790,011 |

| Education Only | N/A | N/A | 99 | 28 | $1,301,781 |

1These totals exclude additional direct funding given each year to Cooperative Extension in every state to support state-level programming on sustainable agriculture.

2The use of a preproposal process varies by region. It serves to screen project ideas for the larger and more complex grant programs, and to reduce applicants' proposal preparation burden as well as the proposal review burden for SARE's volunteer reviewers.

Using an Alternative Feed to Bring Stability in the Face of Drought and Rising Costs

The Challenge

Diana Padilla is a small-scale producer of vegetables and lamb in Harlingen, Texas, located in the Rio Grande Valley. Like many farmers in this dry, southern area, she feels the ongoing financial pressure of persistent drought combined with inflation. As drought impacts forage production, many livestock farmers with limited access to land need to buy more supplemental feed, which has been rising in cost in recent years. At the same time, lamb prices have been fluctuating and reliable access to meat processing has been difficult to find. All of these issues combined have made it difficult for Padilla to track her costs of production and price her lamb accordingly. As a result, she is seeking out ways to bring more financial stability to her operation, for example by growing more of her own feed and, eventually, becoming certified organic.

The Actions Taken

This study highlights moringa as a feasible, cost-effective alternative to alfalfa for lamb feed.

Diana Padilla, Yahweh's All Natural Farm and Garden

Padilla used a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant to explore whether moringa could serve as a viable feed supplement compared to the alfalfa pellets she typically purchases. Moringa is a fast-growing, drought-resistant tree native to India, and research outside the United States has shown that it can replace conventional feeds in a cost-effective way. In her project, Padilla compared bringing lambs to market on a diet of pasture and alfalfa pellets with pasture and farm-grown moringa. She pelletized the moringa before feeding it to her lambs, and evaluated a range of alfalfa/moringa replacement rates, up to 100% moringa. She also tracked her costs of production, including the labor associated with pelletizing her own feed, to develop a clear idea of whether moringa could work as a financial alternative to purchased alfalfa pellets.

The Impacts

Padilla’s initial experiments with adding moringa to her herd’s diet showed promising results, and she plans to continue refining her approach to using the feed so that it can contribute to the long-term sustainability of her farm. Specific impacts include:

- Moringa pellets showed a slight cost advantage over purchased alfalfa pellets and resulted in comparable weight gain for lambs.

- Padilla identified the labor involved in processing moringa as the highest cost to using it as a feed source. Going forward, she plans to see how she can improve efficiency in this area and make moringa even more cost effective.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FS23-348.

Creating Economic Value Out of Waste Materials in Mushroom Production

The Challenge

The project demonstrates clear economic advantages for farmers by turning what was once waste—spent mushroom substrate—into valuable products.

David Wells, Henosis Mushrooms

Fueled by consumer interest, the market for locally produced specialty mushrooms is growing throughout the country. High-value specialty mushrooms can be grown in a range of woody substrates, with compressed sawdust logs being the method that allows for indoor production on the largest scale. Yields from logs drop dramatically after the first flush, so mushroom farmers must make or buy new ones on a regular basis. Although they represent a recurring cost, spent logs do have potential value as a compost material, at least for farmers who also grow vegetables and are in the practice of making their own compost. But according to Tennessee mushroom grower David Wells, these logs aren’t being used to their fullest potential.

The Actions Taken

Wells, who operates a mushroom business called Henosis outside of Nashville, used a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant to show that spent sawdust logs can be used to grow lesser known specialty mushrooms. The mushroom he focused on is called the almond portobello, which can sell for $25-$50 per pound. While more common specialty mushrooms prefer a woody substrate, almond portobellos do well in a more composted environment. So, Wells explored whether it would be economically viable to compost his spent sawdust logs, inoculate blocks of compost with almond portobellos and produce a marketable yield. To do so, he tracked the costs associated with materials and labor plus yields to identify a reasonable price point. After this secondary mushroom harvest, he then had the remaining compost evaluated by Cornell University for its value as a commercial product or an on-farm soil amendment, and he applied it to his own vegetable beds to observe its effect on his other crops.

The Impacts

While he recommends further research to improve efficiency and study the market, Wells demonstrated that instead of looking at spent sawdust logs as waste, mushroom farmers can view them as a potential source of additional revenue streams. Specific impacts include:

- Based on his recordkeeping and economic analysis, producing two 50-block batches of almond portobellos each week could generate an annual profit of almost $17,000 when priced at $24 per pound.

- The final compost Wells added to his own vegetable beds resulted in healthy crops, and based on a lab analysis its quality is comparable to the compost used in the button mushroom industry. This confirmed its value as a second potential income stream, after using it to grow almond portobellos.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FS21-331.

Using Drone Technology to Help Farmers Reduce Nitrogen Use

Nolan Parker (pictured) studied the ability of two types of drones to collect fertility data in his fields: fixed-wing aircraft and quadcopters. Photos courtesy Nolan Parker

The Challenge

As with most of the country, Mississippi’s large-scale row crop farmers struggle to find a balance between environmental stewardship and profitability when it comes to applying fertilizers on their fields. Many farmers over-apply nitrogen beyond the needs of their crop because the prospect of low yields can lead to severe economic losses. Not only are these farmers spending more money on fertilizer than they need to, the excess nitrogen leaches into waterways and ultimately impairs water quality. There are tools available to help farmers tailor their application rates more closely to the actual needs of their crop, and one evolving technology that can be very helpful is the use of variable rate nitrogen mapping with drones. Essentially, drones can be used to collect highly detailed data that indicates a crop’s nitrogen needs throughout a field. Farmers can then apply fertilizer at variable rates based on this data–targeting the rate exactly to the crop’s needs on a row-by-row level.

The Actions Taken

Overall, this study resulted in increased sustainability through a reduction of nitrogen inputs.

Nolan Parker, Parker Farms Partnership

Nolan Parker, a third generation farmer who researched agricultural uses of drones in graduate school at Mississippi State University, used a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant to advance the field further. His two objectives were to test new algorithms related to nitrogen use efficiency in corn and cotton, and to compare the data-collecting ability of two types of drones on his family’s farm: quadcopters and fixed-wing aircraft. At the time quadcopters were the preferred technology in agriculture, but their batteries limited them to covering only about 30 acres at a time, whereas fixed-wing drones were less commonly used but could fly about five times longer. One of Parker’s main goals was to see if the faster speed of the fixed-wing drone resulted in less accurate data collection.

The Impacts

While Parker’s project encompassed only two years on a single farm, the results were insightful and demonstrated this technology can be used to help farmers reduce their nitrogen use. Specific impacts include:

- Parker’s demonstration data from both years showed there is potential to reduce nitrogen below a full fixed rate without affecting yields, in both corn and cotton.

- Field data collected by the fixed-wing aircraft was not significantly different than what the slower quadcopter collected, suggesting both types of technology can be useful in a variable rate nitrogen program.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FS20-321.