Photos by Vander Gac, Northeast SARE

Recent Highlights from the Northeast Region

- We launched the Farming Community grant program in 2025, which seeks to increase the agricultural workforce and protect farmer health by supporting agricultural research and education in areas of social science. The Farming Community grant program has a streamlined application process, designed for ease of access. We anticipate that this will encourage more farmers working with communities to apply as they build and share innovative agricultural knowledge.

- We’re streamlining grant applications across all programs to accommodate the needs of farmers, students, and agricultural service providers. We hope this will assist in contributing to the ever-increasing pool of sustainable agriculture insights and resources being produced in the Northeast. This streamlining includes shorter calls for proposals with revised questions and consolidated appendices.

- We’ve launched a technical assistance program to help first-time grant applicants navigate the grant-writing process—from identifying and designing a successful project to completing a budget and submitting an application. This program was launched as a support mechanism for the Farming Community grant program, and we’re in the process of expanding it to support first-time applicants to our other grant programs. The technical assistance program makes it easier for applicants who aren’t affiliated with land grant universities to access institutional knowledge.

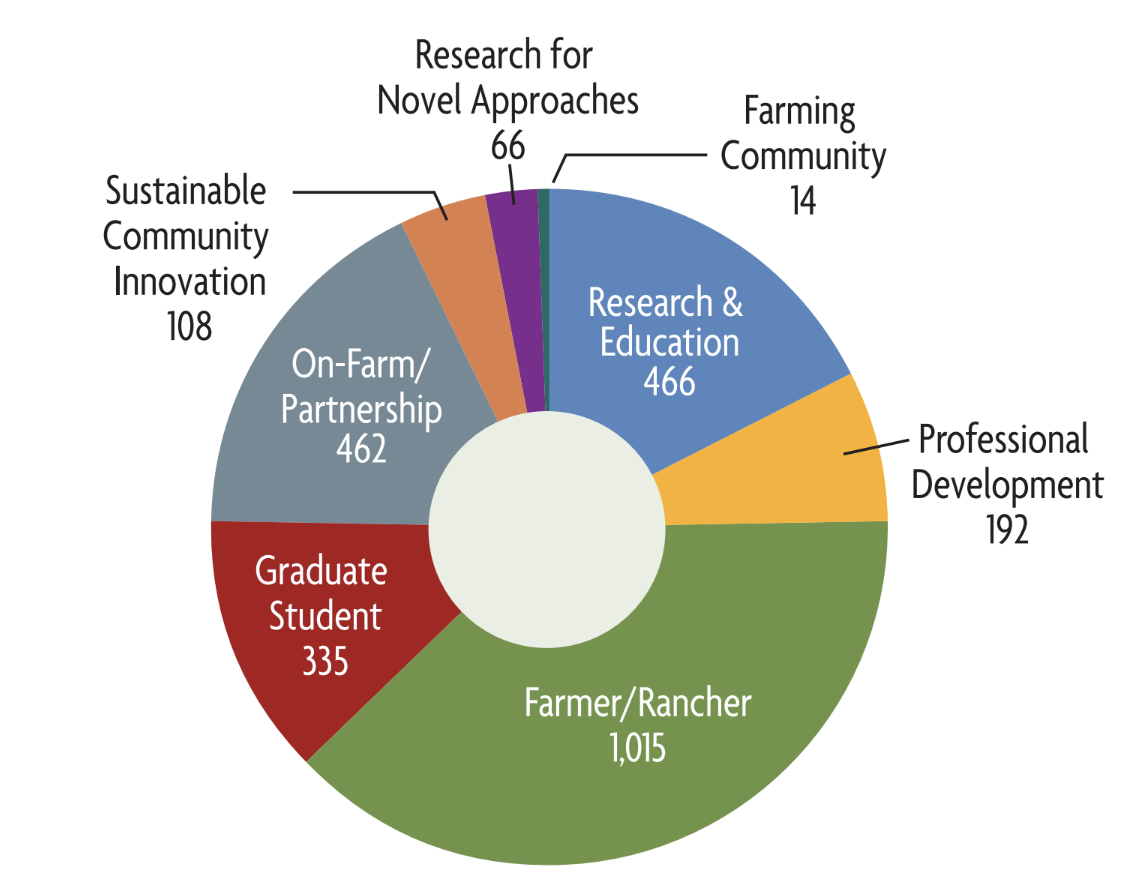

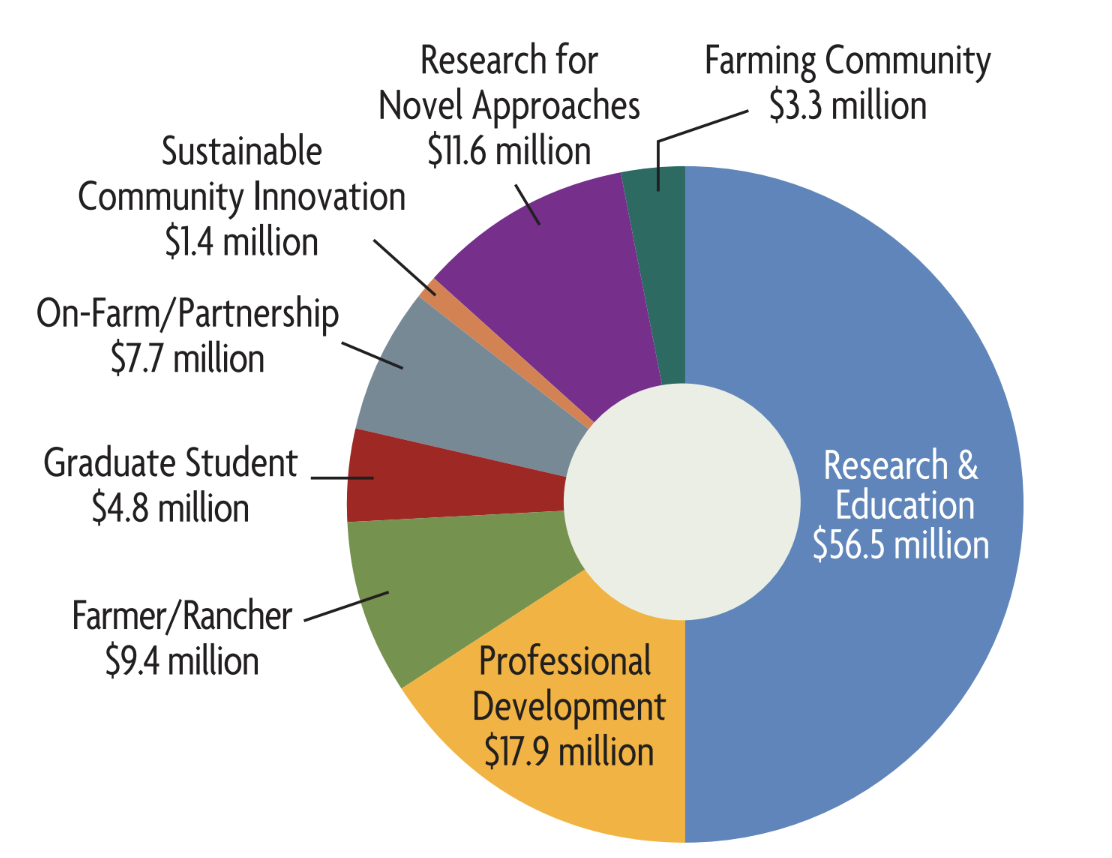

Total Grant Awards 1988-20251

2,644 GRANTS

$112.6 MILLION

Grant Proposals and Awards 2024-20251

| Grant type | Preproposals Received2 | Full Proposals Invited | Full Proposals Received | Proposals Funded | Funding Total |

| Research and Education3 | 82 | 34 | 27 | 10 | $2,625,917 |

| Professional Development Program3 | 37 | 29 | 20 | 8 | $1,211,053 |

| Research for Novel Approaches3 | 111 | 36 | 31 | 9 | $1,755,817 |

| Farmer/Rancher | N/A | N/A | 186 | 66 | $1,667,105 |

| On-Farm Research/Partnership4 | N/A | N/A | 46 | 35 | $959,453 |

| Graduate Student4 | N/A | N/A | 96 | 34 | $504,322 |

| Farming Community5 | N/A | N/A | 168 | 14 | $3,311,490 |

1These totals exclude additional direct funding given each year to Cooperative Extension in every state to support state-level programming on sustainable agriculture.

2The use of a preproposal process varies by region. It serves to screen project ideas for the larger and more complex grant programs, and to reduce applicants’ proposal preparation burden as well as the proposal review burden for SARE’s volunteer reviewers.

3These grant programs were paused in 2024 as part of a grantmaking redesign. They resumed in 2025

4Funding data for 2025 was not available at the time this report was published.

5This grant program was started in 2025.

Reducing Pest Damage and Increasing Profitability for Delaware Bay Oyster Farmers

The Challenge

One of the biggest headaches for oyster farmers along the East Coast is the species of pests commonly known as mud worms. One species settles on the outside of oyster shells, which causes mud to accumulate that reduces oyster growth and can cause mortality. To avoid this, farmers have to hose off their oysters regularly, which is very labor intensive, and therefore an expensive practice. Another mud worm species bores into the oyster’s shell, causing blemishes that can make them unmarketable. There are a handful of practices that reduce this problem, but none are practical enough for oyster farmers to easily adopt them.

The project was eye opening and exceeded our expectation of how it will inform our future farm operations.

Lisa Calvo, Sweet Amalia Oyster Farm

The Actions Taken

Mud worms are widespread in the Delaware Bay, where Lisa Calvo owns and operates Sweet Amalia Oyster Farm, on the New Jersey side. Calvo, who is also a marine biologist, received a SARE Farmer grant to study a new approach to avoiding mud worm damage. In the Delaware Bay, many farmers grow oysters using the “rack and bag” system. This involves growing them in bags that rest on metal racks in the intertidal zone, so they alternate between being underwater and in the air. Most racks are 15” off the ground, and Calvo experimented with 20” and 30” elevations. At a higher elevation, oysters would be exposed to less mud worm damage, but they would also have less time to feed. This would increase the amount of time, and therefore labor, it takes them to reach marketable size. Both of these tradeoffs–less pest damage versus a longer production period–can have a major impact on profitability, which Calvo wanted to evaluate.

Photo by Gab Bonghi

The Impacts

Working with technical advisors at Rutgers Cooperative Extension, Calvo found that each rack height can be financially viable. This is useful because it gives oyster farmers more options based on their situation. The higher racks had more labor costs due to the longer growth time, but the higher yields they produced made them profitable. Specific impacts include:

- Calvo found that increasing rack height by 5”, to the 20” level, increased production time by two weeks but reduced mud worm damage enough that it was more profitable than the standard height.

- She has begun the process of converting all of her racks to 20” as a result, excluding ones that are needed for winter production.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNE23-038.

Turning Woodlots into Revenue Streams with Silvopasture

The Challenge

Many farms in the Northeast include wooded or brushy land that isn’t suitable for food production. As a result, this land has a cost attached to it in the form of property taxes and potentially in maintenance, while it isn’t generating revenue for the farmer. As financial pressure increases on farmers in the region due to higher land and input costs, finding agricultural uses for woodlots can add important revenue streams to farm operations. One emerging avenue for this is silvopasture, or raising livestock among trees. Charles Lafferty, of Skyline Pastures in Mohrsville, Penn., wanted to try raising pigs in his wooded lands, but he found there were critical knowledge gaps in terms of which forage species and tree cultivars would be best for pigs to thrive in.

The Actions Taken

The project successfully demonstrated that pigs can be raised profitably in wooded areas.

Charles Lafferty, Skyline Pastures

Along with farming the land sustainably, one of Lafferty’s long-term goals is to transition to farming full-time, without the need to supplement his income. So, he used a SARE Farmer grant to experiment with rotational grazing of pigs in the wooded lands of his 12-acre farm. He wanted to see what impact this would have on the health of his animals and the forest, as well as profitability. To start, he set up temporary electric fencing in a woodlot to establish paddocks and added necessary infrastructure for the animals, like troughs and shelter. He also established a range of fodder and nut tree species for them. Along with keeping track of costs and revenue, he collected soil data and worked with a forester to conduct plant and tree inventories. Concerned about animal welfare, Lafferty also made sure his pigs had adequate access to food, water and shelter, and were comfortable with being moved from one paddock to another.

The Impacts

Lafferty found that this rotational silvopasture system was profitable, despite its startup costs and the labor associated with managing it. Specific impacts include:

- After factoring in all expenses, the average net profit was $300 per pig. Lafferty also found he was able to rotate between paddocks efficiently, freeing up time for other tasks such as forage management.

- Lafferty saw a 90% survival rate of the fodder and nut tree species he planted, while also observing an improvement in control of invasive species.

- He shared the results of this project directly with more than 50 farmers, through two field days and multiple farm walks.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNE23-053.

Equipping Farmers with Profitable Winter Production Options

The Challenge

The Northeast has short growing seasons and long winters, which traditionally puts a limit on how many crops–and thus how much income–farmers can produce from their land. This long income gap presents one of the biggest challenges to the financial viability of small-scale farms in the region. As a result, there’s a lot of interest in season extension and winter production strategies. These can take many forms, such as growing in high tunnels or producing crops during the growing season that can be stored and sold in the winter, like squash or cabbage. But even these common approaches require resources that many small-scale producers may not have, including the money or space to build a high tunnel, or enough land to grow crops that aren’t sold immediately.

The Actions Taken

I reached new markets and generated a new revenue source during winter months, a time when our farm income is low.

Jennifer Wilhelm, Fat Peach Farm

Supported by a SARE Farmer grant, Jennifer Wilhelm of Fat Peach Farm in Madbury, N.H., successfully demonstrated another approach to winter production that takes advantage of something most growers already have–cold storage rooms. These small buildings are meant to refrigerate crops during the hot summer months, and mostly sit unused during the winter. But with small modifications to add growing lights, shelving, fans and heating, Wilhelm wanted to explore if they could be used effectively to grow microgreens during the winter months. Microgreens are a fast-growing, high-value crop that don’t need a lot of space and are popular with consumers.

During the project, Wilhelm modified her cold storage room and evaluated the yield and profitability of four microgreen varieties: kale, broccoli, mild salad mix and pea shoots. She assessed profitability by doing a budget analysis that included costs for startup, supplies, labor and electricity, as well as income from sales.

The Impacts

Wilhelm found that the project was a success–she was able to grow microgreens, found willing buyers, and determined they were profitable. Specific impacts include:

- Startup costs could be recovered in year one, and she could generate a net income of $1,577 per week from 12 trays of microgreens, and $1,090 per 28-week season from 6 trays of pea shoots.

- Wilhelm learned important lessons about managing soil moisture and heat levels to optimize yields while avoiding mold. She was planning to expand production after the project ended, and to continue improving her system.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNE20-966.