Recent Highlights from the North Central Region

- We’ve launched an online Grant How-To Video Series to help more people feel ready to apply for a SARE grant. These short videos answer common questions and break down the application process in step-by-step detail.

- Since 2012, North Central SARE, the Conservation Technology Innovation Center, and partners have surveyed farmers nationwide about their experiences with cover crops. The 2025 survey highlighted how firsthand experience drives adoption; farm advisors who use cover crops are five times more likely to recommend them.

- Innovation creates opportunity, but it also comes with risk. With SARE support, farmers don’t face that risk alone—through 3,538 collaborations from 2014 to 2024, our grants have brought farmers, researchers, and educators together to share knowledge, test ideas, and navigate uncertainty with greater confidence.

- Farm owners are increasingly asking how they can attract employees and build long-term working relationships. In response, our “Paths to Sustainability with Farm Labor” training in 2025 brought together more than 60 agricultural educators from across the region, providing tools and insights to strengthen farm labor practices. As part of this effort, the event organizers released a new guide, Farming into the Future by Centering Farmworkers, which is now available online.

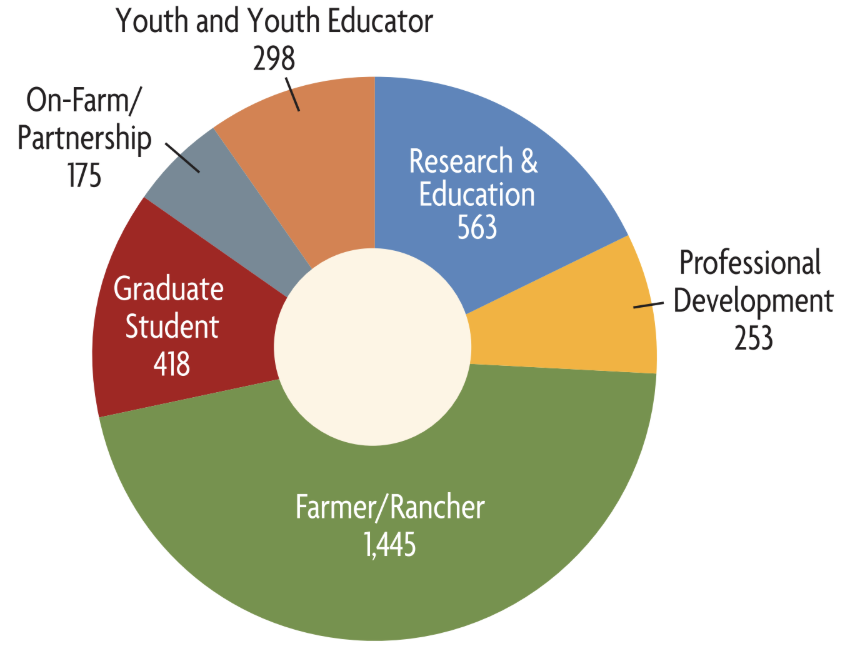

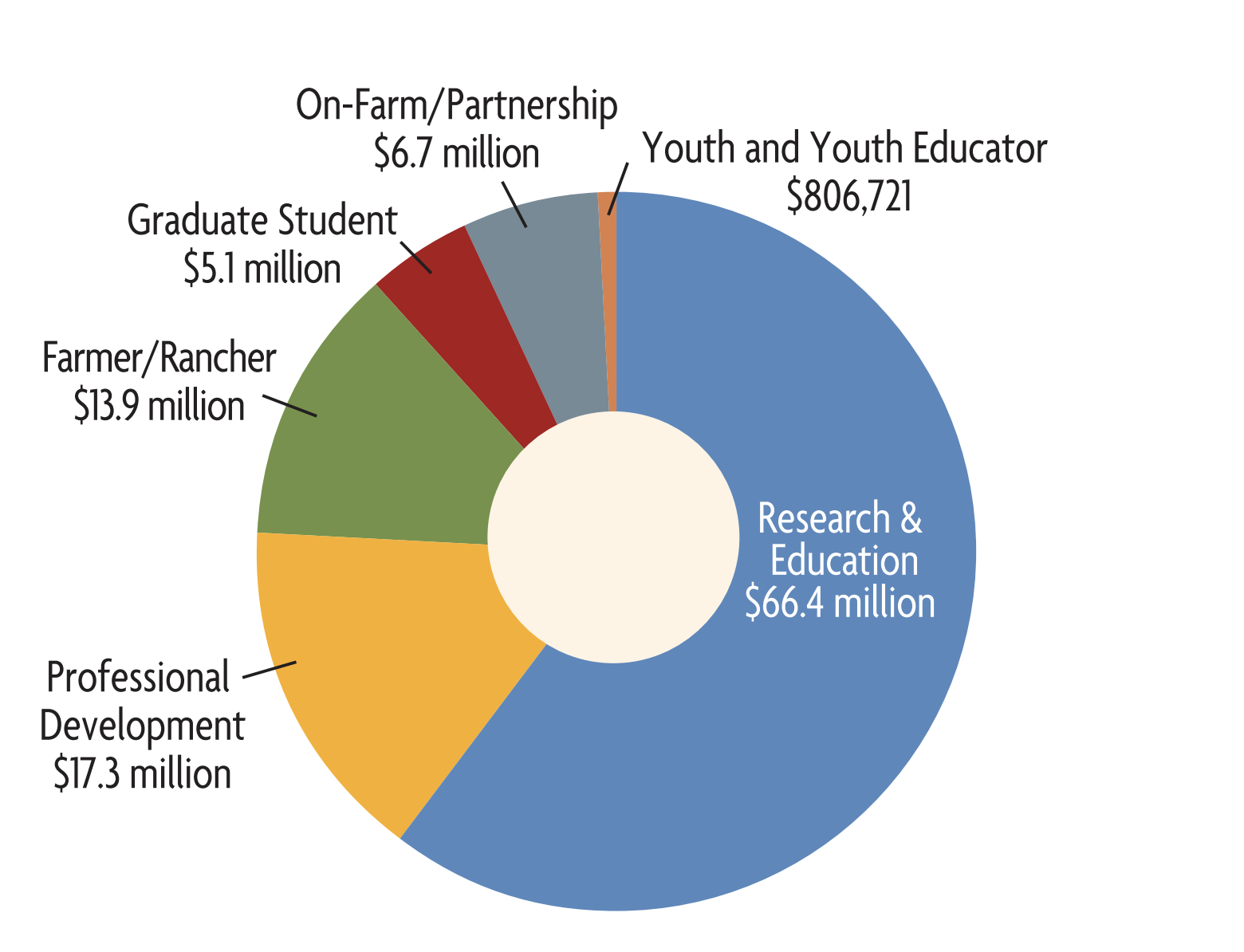

Total Grant Awards 1988-20251

3,152 GRANTS

$110.1 MILLION

Grant Proposals and Awards 2024-20251

| Grant type | Preproposals Received2 | Full Proposals Invited | Full Proposals Received | Proposals Funded | Funding Total |

| Research and Education | 340 | 84 | 80 | 33 | $8,034,491 |

| Professional Development Program3 | N/A | N/A | 25 | 12 | $1,334,650 |

| Farmer/Rancher | N/A | N/A | 300 | 84 | $1,549,127 |

| On-Farm Research/Partnership | N/A | N/A | 99 | 40 | $1,786,242 |

| Graduate Student | N/A | N/A | 201 | 44 | $846,505 |

1These totals exclude additional direct funding given each year to Cooperative Extension in every state to support state-level programming on sustainable agriculture.

2The use of a preproposal process varies by region. It serves to screen project ideas for the larger and more complex grant programs, and to reduce applicants' proposal preparation burden as well as the proposal review burden for SARE's volunteer reviewer

3Funding data for 2025 was not available at the time this report was published.

Utilizing Cover Crops in Wide Row Corn

The Challenge

There are a number of growers and landowners who have taken a great interest in my work. It is intriguing to them because it is so different from their traditional practices

Bob Recker, Cedar Valley Innovation

These days, most farmers are familiar with cover crops and their potential value as a management tool. In the right context, cover crops can reduce erosion, suppress weeds, provide nitrogen, improve water retention or generate revenue as livestock forage. Bob Recker, a farmer and consultant in Iowa, has always had an interest in experimenting with practices that represent a departure from the status quo. His primary focus is on exploring how to leverage sunlight to maximize crop yields, and this recently led him to a radical idea: While some farmers already plant cover crops between rows of corn, he wanted to widen the corn rows significantly to open up more sunlight and allow the cover crops to grow more vigorously. The first thought of most farmers might be that wider rows sounds like little more than lost yields, but Recker wanted to see the real-world effect this practice could have on profitability, productivity and soil health.

The Actions Taken

Recker received two SARE Farmer/Rancher grants to experiment with fields of corn planted in 60- and 90-inch rows, compared with standard fields with 30-inch rows. He collaborated with three farmers near Waterloo, Iowa. On each participating farm, they looked at a variety of inter-row plantings, including a simple cover crop species that a beginner might start with and a more diverse cover crop mix for more experienced farmers. Each farmer included an additional treatment that was based on their own interests. For example, one farmer might use vigorous cover crop growth to focus on building up soil health or to assist the transition to organic, while another might graze the cover crop after harvest to offset yield loss and boost profitability. Another way to improve profitability could be to include a vegetable crop as well as a cover. In the treatment plots, Recker increased the number of plants per row so that the number of plants per acre was consistent across all plots. On all of the farms, he tracked plant growth through the season, weed suppression, biomass, runoff and yield.

The Impacts

Some treatments resulted in surprisingly impressive–but still slightly lower–corn yields, plus other benefits. But, Recker admits that a farmer should only explore this practice if they have a clear goal for doing it, until more is learned about it. Specific impacts include:

- On one farm, the plot with 60-inch rows had 56% less water runoff during rain events.

- In just one season, Recker recorded organic matter increases of 0.2% and 0.3%, which exceeded his expectations.

- In one year, a participating farmer’s corn crop failed due to a dry season, but he still earned a profit from his treatment field because he had planted turnips there, which he sold at a local farmers’ market.

Learn more: See the related SARE projects FNC21-1297 and FNC22-1348.

Diversifying Vegetable Production and Sales with Chicory Crops

The Challenge

“We learned that these crops can be successfully grown in this part of the country and have the potential to be valuable additions to any vegetable farm’s mix of winter crop

Peter Skold, Waxwing Farm

Anna Racer and Peter Skold are full-time farmers at their 40-acre Waxwing Farm in Webster, Minn. In 2020, they had 3–5 seasonal employees but their long-term goal was to grow the business enough to support one full-time employee instead. One way they could bring in more revenue was to expand winter sales. Many small-scale vegetable farmers use high tunnels for season extension and winter sales, but Racer and Skold decided to explore a different strategy. They looked into growing less common chicory crops–Belgian endives and radicchio–that are of interest to high-end restaurants and other specialty markets. Chicory crops are grown in the field and must go through a period of “forcing” after they’re harvested in the fall, where they continue to grow in a dark environment so that their color turns white and their flavor enhances. These crops wouldn’t take up space in a high tunnel because they’re grown in a field and are forced in a separate location, meaning they could provide a unique winter marketing opportunity in addition to high tunnel production.

The Actions Taken

Racer and Skold used a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant to evaluate the feasibility of growing both Belgian endives and radicchio in Minnesota’s climate, and to compare different techniques for harvesting and forcing them in a cold-storage facility. Other goals included assessing the sales potential and profitability of these specialty crops, and sharing their findings with other farmers in the area. To reduce labor costs, Racer and Skold used mechanical planting and harvesting techniques instead of manual ones. After harvest, endives can be forced in a medium of either peat moss or sand. The traditional method of forcing radicchio is to put them in a temperature-controlled hydroponic system, which Racer and Skold set up using water tanks, a simple recirculation pump and an aquarium heater. They worked with their existing restaurant partners to explore the general appeal, sales volume and pricing of these crops.

The Impacts

Ultimately, Racer and Skold learned enough about the production and sales of chicory crops that they plan to develop their market for radicchio and include it in their winter crop planning in the future. Specific impacts include:

- Racer and Skold learned that direct-seeding instead of transplanting, along with proper harvest techniques, resulted in better root systems and more success during the forcing period.

- They found that endives can also be grown successfully in the Midwest but at a lower sales price. Because endives are more familiar than radicchio, they have a larger established market and thus can be grown on a larger scale. But Racer and Skold chose not to pursue endives due to scale constraints on their farm.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNC20-1251.

Using Soil Amendments to Improve Crop Health and Reduce Pest Damage

The Challenge

Advantages to this project include the ability to experiment on a small scale with results that can be applied on a much larger scale

Glendon Philbrick, Hiddendale Farm

Grasshoppers are highly mobile insects that feed on a wide range of plants, making them a significant pest in gardens, vegetable farms, row crop fields and rangelands. They are especially troublesome when their populations are high. Grasshoppers thrive in dry conditions, and as a result they caused widespread damage in the Great Plains during the drought years of 2020–2021. Glendon Philbrick, who operates the 200-acre Hiddendale Farm in Turtle Lake, N.D., saw their devastating effect firsthand. Those years, grasshoppers swarmed and destroyed many of his crops, everything from hay crops, corn and soybeans, to a variety of vegetables. Even in 2022, when conditions were wetter and less favorable to the grasshopper’s life cycle, they were still present in his fields. As an organic farmer he couldn’t rely on synthetic pesticides, so Philbrick wanted to see if he could deter grasshoppers by raising the Brix level (or sugar content) of his crops. Some farmers have observed that pests such as grasshoppers will avoid feeding on crops when the Brix reaches a certain level, because they find the taste undesirable.

The Actions Taken

In 2023, Philbrick received a SARE Farmer/Rancher grant to experiment with this concept on his farm. The primary way to increase the Brix level of a crop is to focus on improving soil health. So, Philbrick tested the effect of different mineral amendments on 20 crops that had suffered grasshopper damage in recent years, including alfalfa, sweet corn, tomatoes, carrots and lettuce. Through his own experience and by talking with researchers, he determined that grasshoppers wouldn’t feed on his crops when they had a Brix level of 12% or higher. In an attempt to increase Brix, he tested five different soil amendments, using only organic-approved products. These treatments included calcium, amino acids, and humic and fulvic acids. Two other treatments were meant to address iron deficiencies or a low potassium-to-nitrogen level, both based on soil test results. During the project, he took weekly Brix measurements using a refractometer.

The Impacts

Philbrick gained useful insights on the influence that different soil amendments can have on the Brix level and quality of many of the crops he studied. Specific impacts include:

- In 2023, grasshoppers were present on his farm but they didn’t cause significant damage.

- Philbrick found that the most notable increases in Brix due to his treatments happened in carrots, sweet corn and tomatoes.

- He shared his findings at a field day with 38 farmers, and 18 reported gaining new knowledge as a result of their participation.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNC23-1389.