Cereal Rye (Secale cereale)

Also called: cereal rye, winter rye, grain rye

Type: cool season annual cereal grain

Roles: scavenge excess N, prevent erosion, add organic matter, suppress weeds

Mix with: legumes, grasses or other cereal grains

See charts for ranking and management summary.

The hardiest of cereals, rye can be seeded later in fall than other cover crops and still provide considerable dry matter, an extensive soil-holding root system, significant reduction of nitrate leaching and exceptional weed suppression. Inexpensive and easy to establish, rye outperforms all other cover crops on infertile, sandy or acidic soil or on poorly prepared land. It is widely adapted, but grows best in cool, temperate zones.

Taller and quicker-growing than wheat, rye can serve as a windbreak and trap snow or hold rainfall over winter. It overseeds readily into many high-value and agronomic crops and resumes growth quickly in spring, allowing timely killing by rolling, mowing or herbicides. Pair rye with a winter annual legume such as hairy vetch to offset rye’s tendency to tie up soil nitrogen in spring.

Benefits of Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Nutrient catch crop. Rye is the best cool-season cereal cover for absorbing unused soil N. It has no taproot, but rye’s quick-growing, fibrous root system can take up and hold as much as 100 lb. N/A until spring, with 25 to 50 lb. N/A more typical (422). Early seeding is better than late seeding for scavenging N (46).

- A Maryland study credited rye with holding 60 percent of the residual N that could have leached from a silt loam soil following intentionally over-fertilized corn (372). A Georgia study estimated rye captured from 69 to 100 percent of the residual N after a corn crop (220).

- In an Iowa study, overseeding rye or a rye/oats mix into soybeans in August limited leaching loss from September to May to less than 5 lb. N/A (313).

Rye increases the concentration of exchangeable potassium (K) near the soil surface, by bringing it up from lower in the soil profile (123).

Rye’s rapid growth (even in cool fall weather) helps trap snow in winter, further boosting winter hardiness. The root system promotes better drainage, while rye’s quick maturity in spring— compared with other cover crops—can help conserve late-spring soil moisture.

Reduces erosion. Along with conservation tillage practices, rye provides soil protection on sloping fields and holds soil loss to a tolerable level (124).

Fits many rotations. In most regions, rye can serve as an overwintering cover crop after corn or before or after soybeans, fruits or vegetables. It’s not the best choice before a small grain crop such as wheat or barley unless you can kill rye reliably and completely, as volunteer rye seed would lower the value of other grains.

Rye also works well as a strip cover crop and windbreak within vegetables or fruit crops and as a quick cover for rotation gaps or if another crop fails.

You can overseed rye into vegetables and tasseling or silking corn with consistently good results. You also can overseed rye into brassicas (369, 422), into soybeans just before leaf drop or between pecan tree rows (61).

Plentiful organic matter. An excellent source of residue in no-till and minimum-tillage systems and as a straw source, rye provides up to 10,000 pounds of dry matter per acre, with 3,000 to 4,000 pounds typical in the Northeast (118, 361). A rye cover crop might yield too much residue, depending on your tillage system, so be sure your planting regime for subsequent crops can handle this. Rye overseeded into cabbage August 26 covered nearly 80 percent of the between-row plots by mid-October and, despite some summer heat, already had accumulated nearly half a ton of biomass per acre in a New York study. By the May 19 plowdown, rye provided 2.5 tons of dry matter per acre and had accumulated 80 lb. N/A. Cabbage yields weren’t affected, so competition wasn’t a problem (329).

Weed suppressor. Rye is one of the best cool season cover crops for outcompeting weeds, especially small-seeded, light-sensitive annuals such as lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, velvetleaf, chickweed and foxtail. Rye also suppresses many weeds allelopathically (as a natural herbicide), including dandelions and Canada thistle and has been shown to inhibit germination of some triazine-resistant weeds (336).

Rye reduced total weed density an average of 78 percent when rye residue covered more than 90 percent of soil in a Maryland no-till study (410), and by 99 percent in a California study (422). You can increase rye’s weed-suppressing effect before no-till corn by planting rye with an annual legume such as hairy vetch. Don’t expect complete weed control, however. You’ll probably need complementary weed management measures.

Pest suppressor. While rye is susceptible to the same insects that attack other cereals, serious infestations are rare. Rye reduces insect pest problems in rotations (448) and attracts significant numbers of beneficials such as lady beetles (56).

Fewer diseases affect rye than other cereals. Rye can help reduce root-knot nematodes and other harmful nematodes, research in the South suggests (20, 448).

Companion crop/legume mixtures. Sow rye with legumes or other grasses in fall or overseed a legume in spring. A legume helps offset rye’s tendency to tie up N. A legume/rye mixture adjusts to residual soil N levels. If there’s plenty of N, rye tends to do better; if there is insufficient N, the legume component grows better, Maryland research shows (86). Hairy vetch and rye are a popular mix, allowing an N credit before corn of 50 to 100 lb. N/A. Rye also helps protect the less hardy vetch seedlings through winter.

Management of Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Establishment & Fieldwork for Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Rye prefers light loams or sandy soils and will germinate even in fairly dry soil. It also will grow in heavy clays and poorly drained soils, and many cultivars tolerate waterlogging (63).

Rye can establish in very cool weather. It will germinate at temperatures as low as 34° F. Vegetative growth requires 38° F or higher (361).

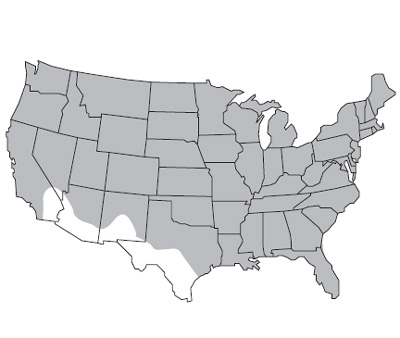

Winter annual use. Seed from late summer to midfall in Hardiness Zones 3 to 7 and from fall to midwinter in Zones 8 and warmer. In the Upper Midwest and cool New England states, seed two to eight weeks earlier than a wheat or rye grain crop to ensure maximum fall, winter and spring growth. Elsewhere, your tillage system and the amount of fall growth you prefer will help determine planting date. Early planting increases the amount of N taken up before winter, but can make field management (especially killing the cover crop and tillage) more difficult in spring. See Rye Smothers Weeds Before Soybeans.

Rye is more sensitive to seeding depth than other cereals, so plant no deeper than 2 inches (71). Drill 60 to 120 lb./A (1 to 2 bushels) into a prepared seedbed or broadcast 90 to 160 lb./A (1.5 to 3 bushels) and disk lightly or cultipack (361, 422).

If broadcasting late in fall and your scale and budget allow, you can increase the seeding rate to as high as 300 or 350 lb./A (about 6 bushels) to ensure an adequate stand. Rye can be overseed by air more consistently than many other cover crops.

“I use a Buffalo Rolling Stalk Chopper to help shake rye seeds down to the soil surface,” says Steve Groff, a Holtwood, Pa ., vegetable grower. “It’s a very consistent, fast and economical way to establish rye in fall.”

Mixed seeding. Plant rye at the lowest locally recommended rate when seeding with a legume (361), and at low to medium rates with other grasses. In a Maryland study, a mix of 42 pounds of rye and 19 pounds of hairy vetch per acre was the optimum fall seeding rate before no-till corn on a silt loam soil (81). If planting with clovers, seed rye at a slightly higher rate, about 56 lb. per acre.

For transplanting tomatoes into hilly, erosion-prone soil, Steve Groff fall-seeds a per-acre mix of 30 pounds rye, 25 pounds hairy vetch and 10 pounds crimson clover. He likes how the threeway mix guarantees biomass, builds soil and provides N.

Spring seeding. Although it’s not a common practice, you can spring seed cereals such as rye as a weed-suppressing companion, relay crop or early forage. Because it won’t have a chance to vernalize (be exposed to extended cold after germination), the rye can’t set seed and dies on its own within a few months in many areas. This provides good weed control in asparagus, says Rich deWilde, Viroqua, Wis.

After drilling a large-seeded summer crop such as soybeans, try broadcasting rye. The cover grows well if it’s a cool spring, and the summer crop takes off as the temperature warms up. Secondary tillage or herbicides would be necessary to keep the rye in check and to limit the cover crop’s use of soil moisture.

Killing & Controlling Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Nutrient availability concern. Rye grows and matures rapidly in spring, but its maturity date varies depending on soil moisture and temperature. Tall and stemmy, rye immobilizes N as it decomposes. The N tie-up varies directly with the maturity of the rye. Mineralization of N is very slow, so don’t count on rye’s overwintered N becoming available quickly.

Killing rye early, while it’s still succulent, is one way to minimize N tie-up and conserve soil moisture. But spring rains can be problematic with rye, especially before an N-demanding crop, such as corn. Even if plentiful moisture hastens the optimal kill period, you still might get too much rain in the following weeks and have significant nitrate leaching, a Maryland study showed (109). Soil compaction also could be a problem if you’re mowing rye with heavy equipment.

Late killing of rye can deplete soil moisture and could produce more residue than your tillage system can handle. For no-till corn in humid climates, however, summer soil-water conservation by cover crop residues often was more important than spring moisture depletion by growing cover crops, Maryland studies showed (82, 84, 85).

Legume combo maintains yield. One way to offset yield reductions from rye’s immobilization of N would be to increase your N application. Here’s another option: Growing rye with a legume allows you to delay killing the covers by a few weeks and sustain yields, especially if the legume is at least half the mix. This gives the legume more time to fix N (in some cases doubling the N contribution) and rye more time to scavenge a little more leachable N. Base the kill date on your area ’s normal kill date for a pure stand of the legume (109).

A legume/rye mix generally increases total dry matter, compared with a pure rye stand. The higher residue level can conserve soil moisture. For best results, wait about 10 days after killing the covers before planting a crop. This ensures adequate soil warming, dry enough conditions for planter coulters to cut cleanly and minimizes allelopathic effects from rye residue (84, 109). If using a herbicide, you might need a higher spray volume or added pressure for adequate coverage. Legume/rye mixes can be rolled once the legume is at full bloom (303).

Kill before it matures. Tilling under rye usually eliminates regrowth, unless the rye is less than 12 inches tall (361, 422). Rye often is plowed or disked in the Midwest when it’s about 20 inches tall (307). Incorporating the rye before it’s 18 in. high could decrease tie-up of soil N (361, 422). In Pennsylvania (118) and elsewhere, kill at least 10 days before planting corn.

For best results when mow-killing rye, wait until it has begun flowering. A long-day plant, rye is encouraged to flower by 14 hours of daylight and a temperature of at least 40° F. A sickle bar mower can give better results than a flail mower, which causes matting that can hinder emergence of subsequent crops (116).

Mow-kill works well in the South after rye sheds pollen in late April (101). If soil moisture is adequate, you can plant cotton three to five days after mowing rye when row cleaners are used in reduced-tillage systems.

Some farmers prefer to chop or mow rye by late boot stage, before it heads or flowers. If rye gets away from you, you’d be better off baling it or harvesting it for seed,” cautions southern Illinois organic grain farmer Jack Erisman (38). He often overwinters cattle in rye fields that precede soybeans. But he prefers that soil temperature be at least 60° F before planting beans, which is too late for him to no-till beans into standing rye.

“If rye is at least 24 inches tall, I control it with a rolling stalk chopper that thoroughly flattens and crimps the rye stems,” says Pennsylvania vegetable grower Steve Groff. That can sometimes eliminate a burndown herbicide, depending on the rye growth stage and next crop.”

A heavy duty rotavator set to only 2 inches deep does a good job of tilling rye, says Rich de Wilde, Viroqua, Wis.

Can’t delay a summer planting by a few weeks while waiting for rye to flower? If early rye cultivars aren’t available in your area and you’re in Zone 5 or colder, you could plow the rye and use secondary tillage. Alternately, try a knockdown herbicide and post-emergent herbicide or spotspraying for residual weed control.

For quicker growth of a subsequent crop such as corn or soybeans, leave the residue upright after killing (rather than flat). That hastens crop development—unless it’s a dry year—via warmer soil temperatures and a warmer seed zone, according to a three-year Ontario study (146). This rarely influences overall crop yield, however, unless you plant too early and rye residue or low soil temperature inhibits crop germination.

Cereal Rye: Cover Crop Workhorse

Talk to farmers across America about cover crops and you’ll find that most of them have planted a cereal rye cover crop. Almost certainly the most commonly planted cover crop, cereal rye can now be seen growing on millions of acres of farmland each year.

There are almost as many ways to manage cover crop rye as there are farmers using it. Climate, production system, soil type, equipment and labor are the principal factors that will determine how you manage rye. Your own practical experience will ultimately determine what works best for you.

Check out how others are managing rye in this book, on the Web and around your region. Test alternatives management practices that allow you to seed earlier or manage cover crop residue differently. Add a legume, a brassica or another grass to increase diversity on your farm.

Reasons for rye’s widespread use include:

- It is winter-hardy, allowing it to grow longer into fall and resume growth earlier in the spring than most other cover crops.

- It produces a lot of biomass, which translates into a long-lasting residue cover in conservation tillage systems.

- It crowds out and out-competes winter annual weeds, while rye residue helps suppress summer weeds.

- It scavenges nutrients—particularly nitrogen —very effectively, helping keep nutrients on the farm and out of surface and ground water.

- It is relatively inexpensive and easy to seed.

- It works well in mixtures with legumes, resulting in greater biomass production and more complete fall/winter ground cover.

- It can be used as high-quality forage, either grazed or harvest as ryelage.

- It can fit into many different crop and livestock systems, including corn/soybean rotations, early or late vegetable crops, and dairy or beef operations.

Fall management (planting) of Cereal Rye Cover Crops:

- While results are best if you plant rye by early fall, it also can be planted in November or December in much of the country—even into January in the deep South—and still provide tangible benefits.

- It can be drilled or broadcast after main crop harvest, with or without cultivation.

- It can be seeded before main crop harvest, usually by broadcasting, sometimes by plane or helicopter, and in northern climates, at last cultivation of the cash crop. Soil moisture availability is crucial to many of these pre-harvest seeding methods, either for germination of the cover crop or to avoid competition for water with the main crop.

Spring management of Cereal Rye Cover Crops (termination) is even more diverse:

- Rye can be killed with tillage, mowing, rolling or spraying.

- It can be killed before or after planting the cash crop, which can be drilled into standing cover crops in conservation tillage systems.

- Some want to leave rye growing as long as possible; others insist on terminating it as soon as possible in spring.

- Vegetable growers may leave walls of standing rye all season long between crop rows, usually to alleviate wind erosion.

Some examples of rye management wisdom from practitioners around the country:

- Pat Sheridan Jr., Fairgrove, Mich. Continuous no-till corn, sugar beets, soybeans, dry beans: “In late August, we fly rye into standing corn (or soybeans if we’re coming back with soybeans the following year). We learned that rye is easier to burn down when it’s more than two feet tall than when it has grown only a foot or less.”

- Barry Martin, Hawksville, Ga. Peanuts and cotton. After cotton, in late October or November, we use a broadcast spreader (two bushels of rye per acre), then shred or mow to cover the seed. We usually get enough moisture in November and December for germination. After peanuts, we use a double disc grain drill (1.5 bushels of rye per acre) in mid-September to mid-October.”

- Bryan and Donna Davis, Grinell, Iowa. Corn, soybeans, hay. We tried to no-till corn and beans into rye three feet tall, but failed. The C:N ratio was way out of whack. The corn looked like it had been sprayed. If you don’t kill before planting, you will invite insects.” See also Oats, Rye Feed Soil in Corn/Bean Rotation.

- Ed Quigley, Spruce Creek, Pa .Dairy. We seed cereal rye (two bushels per acre) immediately after corn silage. We allow as much spring growth as possible up to about 10 inches, at which point it becomes more difficult to kill, especially with cool/overcast conditions. We will also wait to make rylage in spring if we need feed, and then plant corn a bit later.”

In some areas, farmers substitute other small grain cover crops for rye. They are doing so to better fit their particular niches, better manage their systems, or to cut costs by saving small grain seeds. Wheat is a popular alternative to rye. Look around and experiment!

—Andy Clark

Pest Management for Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Thick stands ensure excellent weed suppression. To extend rye’s weed-management benefits, you can allow its allelopathic effects to persist longer by leaving killed residue on the surface rather than incorporating it. Allelopathic effects usually taper off after about 30 days. After killing rye, it’s best to wait three to four weeks before planting small-seeded crops such as carrots or onions. If strip tilling vegetables into rye, be aware that rye seedlings have more allelopathic compounds than more mature rye residue. Transplanted vegetables, such as tomatoes, and larger-seeded species, especially legumes, are less susceptible to rye’s allelopathic effects (117).

In an Ohio study, use of a mechanical under-cutter to sever roots when rye was at mid- to late bloom—and leaving residue intact on the soil surface (as whole plants)—increased weed suppression, compared with incorporation or mowing. The broadleaf weed reduction was comparable to that seen when sickle-bar mowing, and better than flail-mowing or conventional tillage (96).

If weed suppression is an important objective when planting a rye/legume mixture, plant early enough for the legume to establish well. Otherwise, you’re probably better off with a pure stand. Overseeding may not be cost-effective before a crop such as field corn, however. A mix of rye and bigflower vetch (a quick-establishing, self-seeding, winter-annual legume that flowers and matures weeks ahead of hairy vetch) can suppress weeds significantly more than rye alone, while also allowing higher N accumulations (110).

“Rye can provide the best and cleanest mulch you could want if it’s cut or baled in spring before producing viable seed,” says Rich de Wilde. Rye can become a volunteer weed if tilled before it’s 8 inches high, however, or if seedheads start maturing before you kill it. Minimize regrowth by waiting until rye is at least 12 inches high before incorporating or by mow-killing after flowering but before grain fill begins.

Rye Smothers Weeds Before Soybeans

An easy-to-establish rye cover crop helps Napoleon, Ohio, farmer Rich Bennett enrich his sandy soil while trimming input costs in no-till soybeans. Bennett broadcasts rye at 2 bushels per acre on corn stubble in late October. He incorporates the seed with a disc and roller.

The rye usually breaks through the ground but shows little growth before winter dormancy. Seeded earlier in fall, rye would provide more residue than Bennett prefers by bean planting—and more effort to kill the cover. Even if I don’t see any rye in fall, I know it’ll be there in spring, even if it’s a cold or wet one,” he says.

By early May, the rye is usually at least 1.5 feet tall and hasn’t started heading. He no-tills soybeans at 70 pounds per acre on 30-inch rows directly into standing rye cover crop. Then, depending on the amount of rye growth, he kills the rye with herbicide immediately after planting, or waits for more rye growth.

“If it’s shorter than 15 to 18 inches, rye won’t do a good enough job of shading out broadleaf weeds,” notes Bennett, who likes how rye suppresses foxtail, pigweed and lambsquarters. I sometimes wait up to two weeks to get more rye residue,” he says.

“I kill the rye with 1.5 pints of Roundup per acre—about half the recommended rate. Adding 1.7 pounds of ammonium sulfate and 13 ounces of surfactant per acre makes it easier for Roundup to penetrate rye leaves,” he explains.

The cover dies in about two weeks. The slow kill helps rye suppress weeds while soybeans establish. In this system, Bennett doesn’t have to worry about rye regrowing.

Roundup Ready® beans have given him greater flexibility in this system. He used to cultivate beans twice using a Buffalo no-till cultivator. Now, depending on weed pressure (often giant ragweed and velvetleaf) he will spot treat or spray the whole field once with Roundup. Bennett figures the rye saves him $15 to $30 per acre in material costs and fieldwork, compared with conventional no-till systems for soybeans.

Rye doesn’t hurt his bean yields, either. Usually at or above county average, his yields range from 45 to 63 bushels per acre, depending on rainfall, says Bennett.

“I really like rye’s soil-saving benefits,” he says. Rye reduces our winter wind erosion, improves soil structure, conserves soil moisture and reduces runoff.” Although he figures the rye’s restrained growth (from the late fall seeding) provides only limited scavenging of leftover N, any that it does absorb and hold overwinter is a bonus.

Updated in 2007 by Andy Clark

Insect pests rarely a problem. Rye can reduce insect pest problems in crop rotations, southern research suggests (448). In a number of mid- Atlantic locations, Colorado potato beetles have been virtually absent in tomatoes no-till transplanted into a mix of rye/vetch/crimson clover, perhaps because the beetles can’t navigate through the residue.

While insect infestations are rarely serious with rye, as with any cereal grain crop occasional problems occur. If armyworms have been a problem, for example, burning down rye before a corn crop could move the pests into the corn. Purdue Extension entomologists note many northeastern Indiana corn farmers reported this in 1997. Crop rotations and IPM can resolve most pest problems you might encounter with rye.

Few diseases. Expect very few diseases when growing rye as a cover crop. A rye-based mulch can reduce diseases in some cropping systems. No-till transplanting tomatoes into a mix of rye/vetch/crimson clover, for example, consistently has been shown to delay the onset of early blight in several locations in the Northeast. The mulch presumably reduces soil splashing onto the leaves of the tomato plants.

If you want the option of harvesting rye as a grain crop, use of resistant varieties, crop rotation and plowing under crop residues can minimize rust, stem smut and anthracnose.

Other Options for Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Quick to establish and easy to incorporate when succulent, rye can fill rotation gaps in reduced tillage, semi-permanent bed systems without increasing pest concerns or delaying crop plantings, a California study showed (216).

Erol Maddox, a Hebron, MD. grower, takes advantage of rye’s relatively slow decomposition when double cropping. He likes transplanting spring cole crops into rye/vetch sod, chopping the cover mix at bloom stage and letting it lay until August, when he plants fall cole crops.

Mature rye isn’t very palatable and provides poor-quality forage. It makes high quality hay or balage at boot stage, however, or grain can be ground and fed with other grains. Avoid feeding ergot infected grain because it may cause abortions.

Rye can extend the grazing season in late fall and early spring. It tolerates fall grazing or mowing with little effect on spring regrowth in many areas (210). Growing a mixture of more palatable cover crops (clovers, vetch or ryegrass) can encourage regrowth even further by discouraging overgrazing (329).

Management Cautions for Cereal Rye Cover Crops

Although rye’s extensive root system provides quick weed suppression and helps soil structure, don’t expect dramatic soil improvement from a single stand’s growth. Left in a poorly draining field too long, a rye cover could slow soil and warming even further, delaying crop planting. It’s also not a silver bullet for eliminating herbicides. Expect to deal with some late-season weeds in subsequent crops (410).

Comparative Notes

- Rye is more cold- and drought-tolerant than wheat.

- Oats and barley do better than rye in hot weather.

- Rye is taller than wheat and tillers less. It can produce more dry matter than wheat and a few other cereals on poor, droughty soils but is harder to burn down than wheat or triticale (241, 361).

- Rye is a better soil renovator than oats (422), but brassicas and sudangrass provide deeper soil penetration (451).

- Brassicas generally contain more N than rye, scavenge N nearly as well and are less likely to tie up N because they decompose more rapidly.