The goal of ecological management is to reduce pest abundance to tolerable levels through the use of multiple pest control tactics that integrate with crop and soil management. This is opposed to using silver-bullet solutions to control pests. Think of pest management strategies as individual tools in a tool box, which together create a positive environment for crops and beneficial organisms, and a stressful one for pests. Just as you wouldn’t rely on a single tool to fix every problem, you should avoid relying on a single approach to manage pests.

When you integrate multiple control tactics, your production system benefits in the following ways:

- The impacts of individual strategies are strengthened when used together.

- The risk of crop failure is reduced because you are spreading the burden of crop protection across many tactics.

- Environmental disruptions and threats to human health are minimized.

- Pests’ ability to develop resistance or adapt to individual tactics is slowed.

- If properly integrated, operational costs are reduced and profitability is improved by reducing the need for purchased inputs.

Diversify Plants and Animals Within Agroecosystems

With knowledge of the pests and beneficials that inhabit your farm, think of ways you can add plant diversity to the system both across the farm and throughout the seasons. Adding a new crop or cover crop to the rotation can help break up the life cycles of soil-borne diseases, pest insects and weeds. However, be mindful not to follow a crop or cover crop with another from the same plant family (e.g., follow a legume with a legume), as this can make pest problems worse. For ideas about how to choose and integrate new crops into a rotation, explore SARE’s Crop Rotation on Organic Farms. The SARE book Managing Cover Crops Profitably features in-depth profiles of common cover crop species and can help you think through appropriate cover crops to use. Or visit Cover Crops for Sustainable Crop Rotations to explore resources on the multifaceted benefits cover crops provide to your farm.

Grafting and Selecting Resistant Varieties

Some vegetable crops, such as tomatoes, peppers and squashes, have varieties that are genetically resistant to common crop diseases like blights and mildews. Choosing a variety that is resistant to diseases typical of your area is a proactive and relatively simple step you can take to greatly reduce the severity of crop damage from diseases and insects. But it is unlikely to eliminate problems in the long term. Pest outbreaks can still occur in spite of having planted resistant varieties if environmental conditions or poor crop management decisions create the conditions that are ideal for them. Also, repeated use of the same resistant crop variety in a field can encourage more aggressive pathogens that are unaffected by the resistance to thrive. Therefore, you should use resistant varieties in combination with other disease management strategies, such as crop scouting, equipment sanitation and crop rotation. Disease-resistant varieties can have flavor or yield characteristics that are different from available varieties, and these factors should be taken into account.

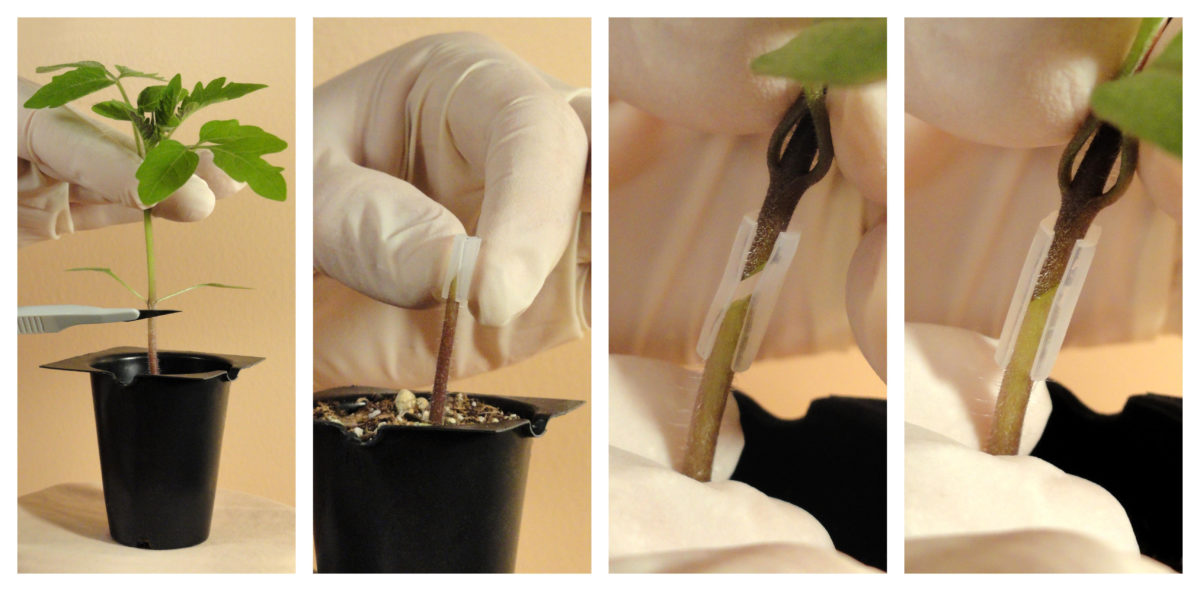

Grafting is an increasingly popular way to gain the benefit of disease resistance without sacrificing a crop’s desirable characteristics. Grafting is especially useful for organic producers, whose disease management options are more limited, and for growers of heirloom crops, as those crops often lack adequate disease resistance. Because grafting is time consuming, you should reserve it for high-value crops such as tomatoes, peppers and melons. The SARE fact sheet Tomato Grafting for Disease Resistance and Increased Productivity describes the grafting process in detail and presents information on the relative resistance of popular tomato varieties to common diseases.

Project Highlight: Evaluating Winter Squash Varieties

Seeking new ways to help farmers manage soil-borne diseases and increase their winter sales, Oregon State University researchers used two SARE grants to explore the potential of different winter squash varieties (SW15-021 and OW16-008). They looked at everything from disease management to storage and marketability. In one project, the team shared integrated disease management strategies with Willamette Valley farmers, including fungal disease symptoms and scouting, crop rotation, fungicide treatments and the use of disease-resistant varieties. In the other project, they used on-farm trials to assess the profitability of different squash varieties, worked with chefs to assess characteristics such as flavor, and created marketing materials for the best-performing varieties. Dozens of farmers in the area adopted new practices as a result of this work.

Project Highlight: Grafting Heirloom Tomatoes

A University of Florida horticulture scientist worked with Frog Song Organics in Hawthorne, Fla., to assess the performance and economics of grafted heirloom tomato varieties in an organic high tunnel system (OS13-083). In the SARE-funded project conducted from 2013 to 2017, the team grafted four heirloom varieties (the “scions”) onto two commercial rootstocks and compared them to the heirloom varieties with no grafting. They found that grafting was effective at managing Fusarium wilt and resulted in healthier, higher-yielding crops overall. In spite of the higher cost of grafting, some scion-rootstock combinations increased revenue 4.5 times due to improved yields.

Include Natural and Semi-Natural Habitats on the Farm

Another way to add diversity is to include perennial plants such as wildflowers, fruit trees and grasses in and around field edges. Flowering perennials stay in place and bloom each year, providing undisturbed habitat rich in nectar, pollen and alternative prey, all of which are attractive to beneficial insects such as lady beetles, ground beetles, lacewings, minute pirate bugs and parasitoids. Perennials boast other benefits, such as extensive rooting systems that trap excess nutrients and pesticides in the soil while promoting soil health, soil biology and water infiltration.

Visit the Native Plants and Ecosystem Services website developed by University of Michigan researchers, with support from SARE, for information about native plants and their attractiveness to beneficial insects. Wherever possible, consider practicing agroforestry and silvopasture by combining trees, shrubs and perennial grasses with crops and livestock to improve habitat continuity for beneficials throughout the farm. The Center for Agroforestry’s (University of Missouri) Agroforestry Training Manual and Handbook for Agroforestry Planning and Design describe agroforestry practices and identify particular species that can be profitably integrated on your land. The book Agroforestry Landscapes for Pacific Islands covers agroforestry practices for producers in tropical regions.

Enhance Natural Enemies

In the United States, natural enemies provide an estimated $4.5 billion worth of pest suppression annually. To take advantage of this valuable service, avoid cropping practices that harm beneficials and instead adopt the practices that support them. In addition to perennials, annual cover crops like buckwheat and cowpeas can establish quickly and provide an early-season food source for natural enemies when their prey is typically scarce. The added ground cover harbors predators such as ground beetles and rove beetles that eat weed seeds and insect pests hiding in the soil. Include vegetative borders and corridors around crop fields to connect beneficials to field edges. Flowering plants established in a field or inside a greenhouse (either in designated rows or in a perimeter) can support natural enemies that are readily available to move into your crop to attack pests. Non-crop vegetation may also hide the crop from pest insects capable of colonizing the crop. Experiment with small plots of vegetational diversity and be sure to consult with local experts.

Check out the University of Wisconsin’s guide Biological Control of Insects and Mites for more information on how to attract and support natural enemies for biological pest control. SARE’s bulletin Cover Cropping for Pollinators and Beneficial Insects has information on the ways you can use cover crops to support important natural enemies and pollinators, and to gain their other benefits. Again, Manage Insects On Your Farm covers whole-farm strategies to support beneficials and includes success stories that illustrate farmer innovations.

Manage Soil to Produce Healthy Crops

Understanding the link between soil health and healthy plants is fundamental to developing ecological pest management strategies. Practices such as conservation tillage, cover cropping and composting promote healthy crops by improving their growing conditions.

Conservation tillage reduces disturbance to the soil’s structure and to soil food webs. It leaves vegetation on the surface that protects the soil from erosion. Cover crops add living roots in the soil that compete with weeds, keep soil in place and reduce compaction.

Once terminated, cover crop residues add organic matter that promotes important beneficial soil biology. This includes soil invertebrates and microorganisms like mycorrhizal fungi that help your crop scavenge otherwise out-of-reach nutrients, as well as other beneficials that prevent disease-causing organisms from infecting the crop.

Composts and manures improve water-holding capacity, suppress disease organisms and provide stable plant-available nutrients to your crop. When grown in healthy soils, crops have access to enough nutrients to support the natural physical and chemical defenses they rely on to resist pathogens and insect pests.

Learn more about soil health practices by exploring SARE’s What is Soil Health? interactive infographic and Building Soils for Better Crops book. SARE’s Steel in the Field includes profiles of weed and soil management implements, while Cornell University’s Resource Guide for Organic Insect and Disease Management describes cultural practices you can use in a variety of crops.

Project Highlight: Rolled Cover Crops

In vegetable production trials (LNE10-295) at Rodale Institute in Kutztown, Penn., rolled cover crops provided effective weed suppression compared to the use of black plastic mulch. At the same time, the cover crop significantly reduced labor costs and eliminated plastic waste. A rolled rye and rye-vetch cover crop had only 5% of the weeds as compared to beds planted with black plastic. In addition to smothering weeds, the cover crop provided organic matter and reduced soil erosion. Learn more about ecological approaches to weed management in Rodale’s guidebook, Beyond Black Plastic.

Minimize Agricultural Disturbances on the Farm

Although they are sometimes necessary for pest management, agricultural disturbances should be minimized to avoid disrupting the beneficial relationships and processes that ecological strategies build. Think of ways to reduce excessive tillage. This can be done by adopting conservation tillage options like no-till, strip-till and ridge till, as well as by reducing the frequency of tillage. Switching to a less disruptive implement like a chisel plow instead of a moldboard plow is another way to reduce soil disturbances. In no-till settings, growers typically rely on residual and pre-emergent herbicide applications to keep weeds low, but this encourages herbicide-resistant weeds to develop. Combine no-till with high-biomass cover crops like cereal rye to ease the pressure of herbicide-resistant weeds. Integrate grazing, wherever feasible, to manage weeds in reduced-till and no-till fields.

The SARE bulletin Cover Crop Economics provides a detailed explanation of how a cereal rye cover crop can pay for itself within the first two years when used to manage herbicide-resistant weeds. When the cereal rye produces enough biomass to smother weeds, growers can get by with fewer applications of lower-cost residual and post-emergent herbicides.

Pesticides are often another source of disturbance on the farm. They reduce biodiversity by destroying non-crop vegetation, which is an important overwintering site for beneficial organisms. They may also kill non-target insects that are beneficial or that serve as alternative prey to important natural enemies. Consider strategies like perimeter trap cropping, where you surround the perimeter of a crop field with another, more attractive variety that lures problem pests away from the cash crop. Target the trap crop border with a selective pesticide to kill the target pests and reduce the total volume of pesticide applied.

Project Highlight: Trap Cropping

In muskmelon production in Iowa, a combination of perimeter trap cropping and delayed row cover removal (LNC13-350) showed promise for managing cucumber beetles and the bacterial wilt pathogen that these beetles transmit. Researchers found that a two-row perimeter of the more attractive buttercup squash lures colonizing cucumber beetles away from the muskmelon cash crop. Applying an insecticide to only the trap crop reduces the overall amount of insecticide used by 59% and maintains effective insect and disease suppression. Learn more about the project and about perimeter trap cropping in the project webinar.

Create Multiple Stresses for Pests

A key tenet of ecologically based pest management is to create a healthy environment for the crop and one that stresses and deters pests. Knowledge of problem pests, their behaviors and life cycles is critical when determining the tactics to use. Consider the pest’s resource and habitat needs, when and how they colonize crop fields, and the beneficial organisms that attack them. Then, apply ecological strategies that will work against their preferences.

For example, disrupt a pest’s habitat by rotating to a new non-host crop. Insects and diseases that specialize in a particular crop will have a hard time without their host. Reduce weeds’ access to sunlight by using narrower crop row spacing or with cover crop residues. Experiment with wider row spacing to minimize the humid conditions that fungal and bacterial crop diseases thrive in. Disrupt the ability of insect pests to disperse across your farm by bordering crop fields with non-host plants. This strategy works by jumbling the visual and chemical cues that pest insects use to locate host crops. Mating-disruption pheromone traps can confuse mate-seeking insects and lower the pest’s ability to reproduce. Sanitizing your harvest and weeding equipment between uses can also reduce the spread of weed seeds or pathogens across your farm.

The SARE fact sheet Ecological Management of Key Arthropod Pests in Northeast Apple Orchards provides examples of these strategies in action for common orchard pests in the Northeast. Cornell University’s Resource Guide for Organic Insect and Disease Management offers examples of ecological strategies that can be used to manage common pests in the production of vegetable crops.

Project Highlight: Deterring a Pest with Cover Crops

The flatheaded appletree borer, a longtime orchard pest, has a hard time finding host trees to lay eggs in when cover crops are involved. A farmer and a team of researchers from Tennessee State University (OS14-084) overseeded winter cover crops into their maple nurseries to manage appletree borers and weeds. They found that growing a mix of crimson clover and annual rye between transplanted trees reduced borer damage by up to 95%. The cover crop created unfavorable habitat for the pest by acting as a barrier that hid host tree trunks from foraging appletree borers. Further, the cool, shaded environment provided by the cover crop reduced weeds and deterred appletree borers, which prefer to lay their eggs on warm, sunny, low-lying areas of host trees. The cover crop was as effective as the conventional approach, which used insecticides and herbicides.

Project Highlight: Physical Pest Exclusion

Plagued with the invasive spotted wing drosophila (SWD) on her farm in New York, berry producer Dale Ila Riggs recalled losing 40% of her blueberry crop and 25% of her raspberry crop to an infestation in 2012. With the help of a SARE grant (FNE14-813), she tested exclusion netting as a tactic to keep the flies off her berry crops and to keep the number of sprays down. Riggs found that exclusion netting worked very well on her operation, reducing infestation levels of SWD in covered berries to less than 1%. The next year, exclusion netting was even more effective at reducing SWD compared to uncovered, sprayed berries that received as many as five insecticide applications during harvest season. Read more about SWD management in these related publications:

- Management Recommendations for Spotted Wing Drosophila in Organic Berry Crops

- Integrated Strategies for Management of Spotted Wing Drosophila in Organic Small Fruit Production

- Spotted Wing Drosophila Pest Management Recommendations for Southeastern Blueberries

For further reading about high tunnel production, visit SARE’s High Tunnels and Other Season Extension Techniques.

Reduce Excess Sources of Nitrogen

Fertilizers may be important tools in crop production, but when applied in excess they can inadvertently support pests and impair water quality. For soil fertility, have your soil tested regularly to identify and set nutrient management goals. Legume cover crops can provide supplemental nitrogen and grass cover crops can take up soil nitrogen. Manures and composts can provide much-needed nutrients in their organic forms. Organic amendments like cover crop residues, manures and composts slowly release plant-available nutrients that feed the crop and soil biology, and build soil organic matter. SARE’s Building Soils for Better Crops provides an in-depth discussion on producing resilient crops by managing soil health and nutrients.

As a Last Resort, Use Targeted Attacks

Because of their potential to reduce on-farm biodiversity and harm the environment, pesticides should only be used as a last resort. Use Integrated Pest Management (IPM) scouting guidelines to determine if and when a pesticide is needed. Visit the National Integrated Pest Management Database and the Regional IPM Centers Resource Database. They are searchable databases, maintained by USDA’s Regional Integrated Pest Management Centers, that contain crop profiles, fact sheets, pest management guidelines and strategic plans.

- Identify: Begin by scouting plants regularly to identify problem pests and to monitor their numbers.

- Evaluate: With the help of local Extension agents and publications, evaluate whether the pests you identify are economically important by comparing them against pest thresholds.

- Prevent: Early on, plan for and integrate biological and cultural management options that promote beneficial ecosystem services and prevent pest problems.

- Action: In the event that a pest reaches its action threshold, take action by determining the appropriate pesticide or biological control tactics to use.

- Monitor and evaluate: After treatment, continue to monitor pest numbers in order to evaluate the effectiveness of your strategy.

As a general rule, begin with the least toxic products if a reactive control is required. Examples include selective pesticides, growth regulators, microbial toxins, feeding deterrents, pheromones and plant-based oils that target problem pests. Natural predators are not as affected by these controls and thus are better able to continue their attack on crop pests. Be sure to keep a running log of the pests and beneficials that visit your fields. This information can help you forecast and plan for pests that may show up. You can also use this information to plan and refine your pest management plan in future years.

Project Highlight: Targeted Sprays Control Stink Bugs

Research in New Jersey (ONE14-217) found that producers can reduce insecticide applications by as much as 75% to manage brown marmorated stink bugs and other orchard pests. Knowing that brown marmorated stink bugs colonize orchards from woody field edges, producers targeted the orchard perimeter with insecticide applications, instead of targeting the entire plot. This method, when combined with IPM-based monitoring and trapping, conserved natural enemies in the orchard by reducing the total volume of insecticide applied and saved growers 25-60% in application costs. Ecological Management of Key Arthropod Pests in Northeast Apple Orchards is a related fact sheet that discusses ecological strategies to manage this pest complex in apples.

Project Highlight: Control of White Mold with a Biopesticide

White mold, an important fungal disease in snap beans and other vegetable crops nationwide, is managed with the help of a fungal parasite, Coniothyrium minitans. Applied as a fungal biopesticide, C. minitans specifically attacks and kills the pathogen that causes white mold. Adding cultural practices like resistant variety selection, crop rotation and reduced tillage lowered white mold disease severity in beans from 11% to 3% during a SARE grant project (SW09-031). Watch a summary of the project and other ecological strategies to manage crop pathogens in this webinar.