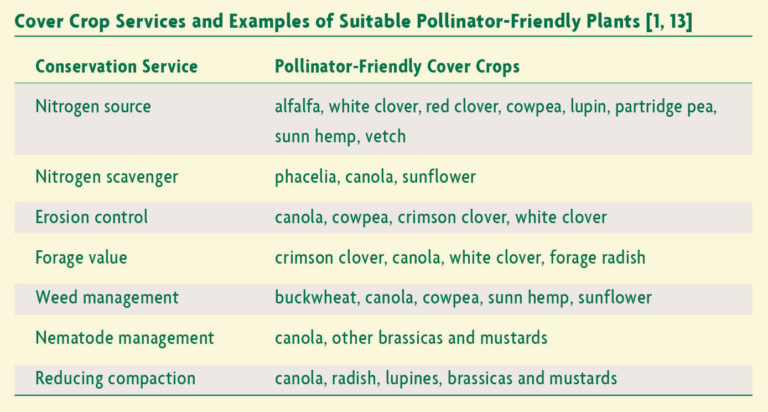

The plants that best fit your needs will vary by location and purpose. Different cover crops have different strengths. Flowering broadleaf species are a must when selecting cover crops for pollinators. Grass cover crops do not provide nectar and their pollen typically has lower protein content than the pollen of broadleaf plants, thus making them only marginally attractive to bees. A flowering plant/grass blend may be an ideal solution in situations where a grass crop is needed to achieve other management priorities, such as preventing nutrient leaching.

You have more flexibility when selecting plants in support of predator and parasitoid insects for pest management, with certain grass cover crops supporting alternate prey (such as aphids) to help sustain the beneficial insects when cash crops are absent.

Avoid cover crops that serve as alternate host plants for crop diseases and those that support large numbers of crop pests. An alternate host is another species, different from the cash crop, which serves as a reservoir for the pest or is necessary for the pest to complete its life cycle. For example, if you are growing a brassica vegetable crop, do not cover crop with another brassica, as it would support similar pests.

However, cover crops that support low levels of crop pests may be valuable in some cases, as they can provide a consistent food source for beneficial predators. This is well documented in the case of pecan orchards with a clover understory [14]. The legumes attract aphids, which are followed by beneficial insects. When the clover dies back and the aphid population drops, the beneficial insects are driven up into the trees. These insects, in search of other foods, manage pests on the developing pecans [14].

Be sure the cover crop you choose is adapted to local conditions. A good first step is to look around you and see what works for other farmers. Red clover and crimson clover are popular cover crops for nitrogen fixation east of the Mississippi River [3]. Red clover is a low-bloat legume that is excellent forage for grazing animals. Clover is also a high-value honey plant. Rapeseed and other brassicas are used for pest and nematode management in fields (biofumigation). Cowpeas, another legume, are exceptionally heat and drought tolerant. They also have extra-floral nectaries—or nectar-producing glands at leaf stems—which attract beneficial insects. These plants are used for erosion control across the Southeast and coastal California [3]. They are also used for weed suppression in the Deep South. Buckwheat is useful as a rapid-growing smother crop in much of the United States [3], and it is the premier cover crop for attracting beneficial insects.

Of course, buckwheat is not ideal for every situation. Hoping to use buckwheat as a nectar source for predators of the glassy-winged leafhopper, a vineyard pest [15], SARE-funded University of California-Riverside Extension specialists found that the plant struggled to grow during the hot, dry southern California summer. Sustaining the cover crop with irrigation turned out to be an expensive proposition, and actually increased populations of the blue-green sharpshooter, another local vineyard pest. Ultimately the buckwheat did in fact increase predator numbers to help manage glassy-winged leafhoppers, but that benefit became more difficult to justify when balanced against unexpected challenges.

Finally, when considering plants, a strong case can be made for the role of diversity. Using a SARE grant, a graduate student researcher in Florida [16] found significant differences in wild bee abundance and diversity based upon the number of crops present on a farm. At one end of the spectrum, the farm with the fewest number of bees (five species) grew only two crops and mowed directly up to the field edges. The farm with the greatest abundance of bees (14 species) grew nine crop species and maintained open, unmowed buffer areas around the farm. Interestingly, both farms were relatively similar in size. While not explicitly demonstrated in the study, it seems likely that multi-species cover crop mixes are a relatively simple way to expand plant diversity on a farm, with probable benefits to bee abundance and diversity.

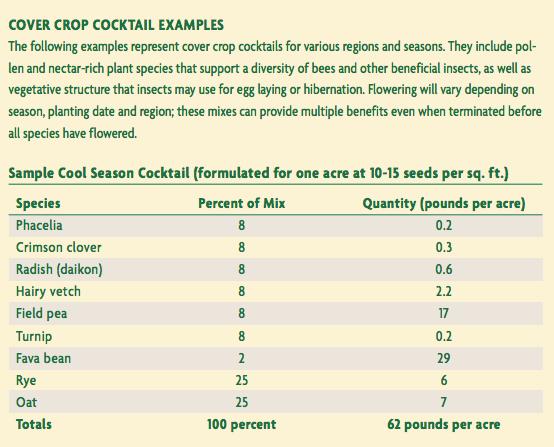

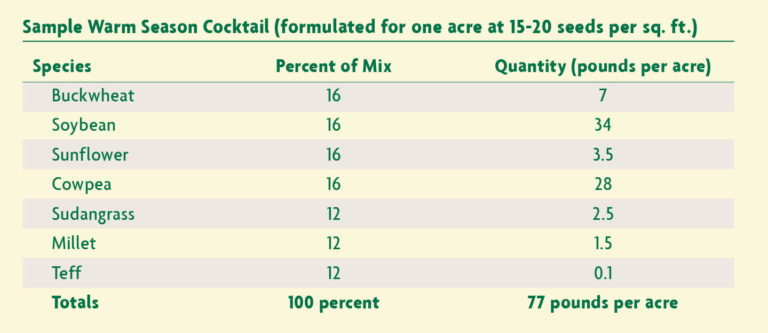

Cover Crop Cocktails

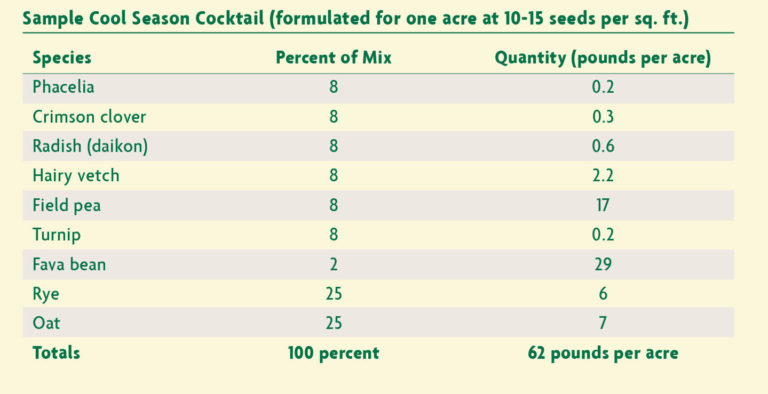

Mixtures of cover crops, or cocktails, have synergy—they generally work better than each single species could alone. In fact, a planting of legumes and grasses can result in an overall increase in available nitrogen [17]. Legumes build up soil nitrogen quickly, but their residue also decomposes quickly, releasing nutrients. A small grain does not add soil nitrogen, but it is an excellent nutrient scavenger. Additionally, its residue decays over a longer period of time, providing a slow-release mechanism for soil nutrients. Small grains are also useful for controlling erosion, preventing nutrient leaching and suppressing winter weeds. Mixing the fertilizing effects of the flowering legume with the soil-building small grain can be a winning combination for winter cover [1, 18].

A pollinator-oriented cocktail may include a mix of plants that have different strengths and which flower at different times. Buckwheat, rapeseed, lupines, phacelia, sunn hemp, cowpeas, partridge pea, sunflowers and many clovers are all cover crops that are also beloved by bees and beneficial insects. Stacking these pollinator plants in one field can lengthen the bloom period. For example, if rapeseed blooms in early spring and is harvested in May or June, then it can be followed by the late-summer blooming sunflower, which can then be over-seeded with a winter legume/small grain mix. The rapeseed serves to manage nematodes, the sunflowers mine nutrients and bring them to the surface, while the legume/grain mix adds nitrogen and prevents winter erosion. This is just one path using an all-pollinator rotation for season-long flowers. All of these plants except the small grain have flowers highly preferred by pollinators and other beneficial insects.

Common and Suggested Rotations

There are a number of rotations that work well with common crops, and there is likely to be a proven cover crop rotation that works with your system. The NRCS Cover Crop Economics Decision Support Tool, released in 2014, comes pre-loaded with example scenarios to help farmers think about the economics of including cover crops in their system. For example, in a three-year corn/soybean/corn rotation with fall cover crops every year, including a winter cover crop of cereal rye following corn and a cocktail of cereal rye/crimson clover/brassica following soybeans had long-term benefits in terms of fertilizer and pesticide savings, with no reduced yield [6]. In another scenario, a two-year cotton/corn rotation that included winter cover crops of crimson clover following cotton and a cereal rye/crimson clover/brassica cocktail following corn provided immediate financial and environmental savings [6]. Brassicas, such as mustards, oilseed radishes, tillage radishes, canola and others, are often part of vegetable rotations because of their role in managing soil pests.

There are other examples of successful rotations. In Ohio, a typical corn/soybean rotation might include the cover crops cereal rye, wheat, cowpea and sunn hemp [19]. Brassicas are also an option for a winter cover crop. In Missouri, it is possible to double-crop buckwheat or sunflowers after harvesting a winter crop of canola or wheat in early summer [20]. After winter wheat, Michigan State University Extension recommends the soil-improving cocktail of annual ryegrass/red clover/hairy vetch/oilseed radish to add nitrogen, reduce compaction and improve tilth [21]. Alternatively, the cocktail of crimson clover/annual ryegrass provides many of these same benefits, minus the soil aeration, and is also excellent pasture [21].

A new, cost-efficient rotation is meadowfoam (Limnanthes alba), a winter annual, following seed grasses. Grown in northern California and Oregon, meadowfoam over-winters as a rosette. Its dense flowers attract pollinators and beneficial insects in the spring. This emerging species is useful as both a cover crop and an oilseed. The oil produced is highly shelf stable, and is quite valuable to the cosmetics industry. However, seeds can be hard to find.

TABLE: Relative Value of Cover Crop Species to Bees and Other Beneficial Insects.

NATIVE AND NEARLY NATIVE COVER CROP MIXES

Extensive research demonstrates that native plants foster more abundant and diverse pollinator populations than non-native plant species. Similarly, other benefits of native plants, such as their adaptation to local climate conditions, are well understood. However, the vast majority of cover crop options consist of non-native plants. There are some exceptions, described below.

Phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia), a vigorous-growing annual native to California, and common sunflower (Helianthus annuus), a native of western prairie and desert states, are two species that continue to be more common in cover crop applications. Both are also extremely attractive to honey bees and a variety of native bees. While phacelia (first used as a cover crop in Europe) is sometimes planted as a single-species cover crop, both it and sunflower are increasingly used as part of diverse cover crop cocktails. While those cocktails still do not resemble true native plant communities, the inclusion of these plants within their native range may provide special benefits to local pollinator species.

More work is needed to identify and increase the availability of promising native plant species. Across eastern, southern and Midwestern states, for example, partridge pea (Chameacrista fasciculata), a native annual prairie legume, shows particular promise. In addition to its ability to fix nitrogen, partridge pea attracts large numbers of pollinators and beneficial insects with both flowers and extra-floral nectaries (nectar-producing glands located at leaf stems). The abundant biomass production, trailing vetch-like growth habit and low-cost commercial availability also make partridge pea an attractive cover crop choice for warm-season applications.

While additional research is needed, farmers looking to experiment with local native plants as cover crops might seek out readily available, low-cost wildflower species and begin including them in cocktail seed mixes at a low rate. Annual species such as California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), Douglas meadowfoam (Limnanthes douglasii) and plains coreopsis (Coreopsis tinctoria) may soon take their place alongside crimson clover and buckwheat in creating diverse cover crop seed mixes that blur the lines between agriculture and ecology.

SPECIAL CONCERNS: TERMINATION AND RESIDUE MANAGEMENT FOR GOOD BUGS

While necessary to prepare for cash crop planting, the process of terminating a cover crop can be very detrimental to pollinators and beneficial insects, especially when the cover crop is actively flowering when terminated. The risks to insects from cover crop termination include direct mortality, such as being crushed by cultivation or roller-crimping equipment; and indirect harm, such as the rapid loss of available food sources. Even when adult insects are not present and active in cover crops, nest sites, eggs and hibernating adults may all be present in the crop canopy or upper soil surfaces.

Adopting cover crops for pollinators takes careful planning and consideration. To reduce some of the impact of cover crop termination, we recommend the following:

- Where possible, wait until most of the cover crop is past peak bloom before termination.

- If waiting until peak bloom is not possible, consider leaving strips of the cover crop standing to prevent the crash of beneficial insect populations. With buckwheat, for example, stagger planting and mowing row by row (or groups of rows) to lengthen the bloom period while still preventing buckwheat from reseeding.

- Terminate with as little physical disturbance as possible. For example, roller-crimping may be less disruptive to pollinator nests in the soil than cultivation.

- Maintain permanent conservation areas on the farm to sustain beneficial insects in the absence of the cover crop.

- Leave as much cover crop residue as possible to protect beneficial insect eggs and any hibernating adults.

- Minimize insecticide use in the cash crops that follow cover crops to avoid harm to beneficial insects that may still be nesting in crop residue. At a minimum you should follow a comprehensive integrated pest management (IPM) plan that includes specific risk mitigation strategies that protect pollinators and beneficial insects.