Give Learners Choice in Content, Process and Outcomes

A learner-centered educational program gives participants choice in content, processes and outcomes, which motivates them to stay engaged.

The Science Behind the Practice

Choice is a powerful motivator in adult learning. Like basic emotions, perceiving and making choices are regulated by brain functions designed to help humans survive and thrive. Humans need to perceive they have choices in order to have a sense of control, or agency, over their environment. Otherwise, they would constantly feel threatened: on “high alert” and in “survival mode.”

Agency is the capacity of an individual to act on their own behalf. Agency is important in fundamental aspects of adult life, like relationships, work and productivity, creativity, and learning. In adult education contexts, offering adults opportunities to make choices as they learn promotes agency. Choice is essential in developing the drive, or motivation, to learn.

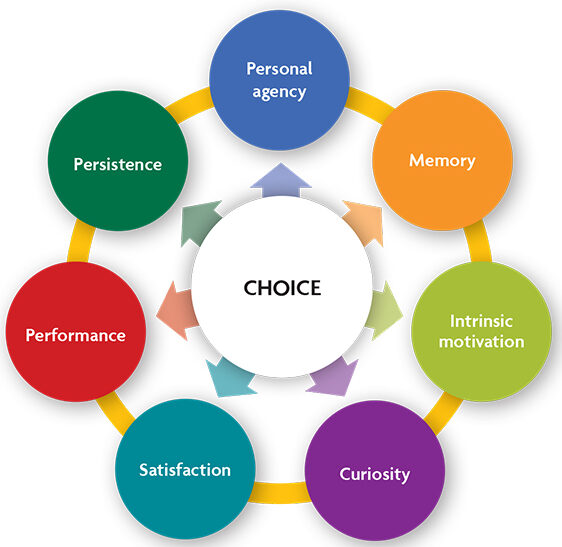

The link between choice and motivation is supported in brain research (Leotti et al. 2010). When individuals are presented with a choice, parts of the brain responsible for processing reward—the reward neural network—is activated. Simply having a choice activates the reward network, and when a choice is made, the network reinforces the perception that what was chosen feels like a reward. This explains why, if you offer adult learners the opportunity to choose their own topic for a project, they will value that topic and enjoy working on it more than if you assigned them the exact same topic. Choice makes the difference between “my project” and “your project” (Figure 2).

Simply having a choice activates the reward network, and when a choice is made, the network reinforces the perception that what was chosen feels like a reward.

Learners will also be more motivated to do well in the project, to persist if they run into obstacles and to develop a personal connection with the topic. These are characteristics of intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is the result of a complex set of neural networks that become active once individuals engage in an activity of their choosing. These networks are responsible for adults wanting to engage in the activity, keeping their attention focused on the activity, and enabling them to think about the activity and themselves as interconnected rather than as separate entities.

The perception of choice and the outcomes of making choices benefit learning in a variety of other ways (Murayama et al. 2017), including:

- Choice enhances curiosity.

- Choice enhances our ability to remember things related to the choice.

- Choice reduces stress associated with learning. It does this in two ways:

- Choice regulates emotions. Giving someone a choice when they are upset acts like a “reset button” for negative emotions. It helps calm them down.

- Choice reduces cognitive dissonance (i.e., the mental discomfort associated with having two conflicting beliefs or values). Although cognitive dissonance can challenge individuals to seek out new learning to resolve the conflict they feel, too much dissonance can be stressful and can shut down learning. Offering choice at this juncture can jump start learning again.

The benefits of choice occur when choices are directly relevant to learning, for example choosing a topic for a project, choosing when to submit a project, or choosing the members of a project team. Benefits also occur when choices are relatively inconsequential to learning, for example letting learners pick the order in which they present their work to the whole group. Because the brain processes making a choice as a reward, even a seemingly insignificant choice, like letting learners pick the color of the markers they use on flip chart paper, can serve to regulate emotions and enhance motivation.

When you are considering how to offer choice during agricultural programming, three areas to think about are the learning content, process and outcomes. Content refers to the curriculum (topics and/or skills) to be learned. Process is the actual methods you use to teach as well as the processes adults may use to learn, such as reading, taking notes, memorizing and talking with peers. Outcomes refer to learners’ growth in knowledge, skills and values, and the ways their accomplishments are demonstrated or displayed.

As agricultural educators, you will want to take into consideration when to offer farmers choice during their learning. Giving farmers choices that directly relate to the content early in a learning event or program is especially helpful in promoting engagement among individuals who initially have a low level of interest. In a half- or full-day workshop, you can use breakout groups within the first hour or two and give participants a choice about what aspect of the content their group will focus on for review or application. For example, in exercises targeted to planning and budgeting, give farmers the choice to form groups based on crop enterprise of interest. For study related to food safety requirements and product specifications, let farmers group by market channel. When discussions focus on cover crop decisions, offer the option to form groups based on crop rotation. And for learning about personnel management options and regulations, give farmers the choice to group by labor concern. This combination of early social interaction and choice can be very effective in getting farmers actively engaged.

Giving farmers choices that directly relate to the content early in a learning event or program is especially helpful in promoting engagement among individuals who initially have a low level of interest.

You can offer similar choices in online learning events by allowing farmers to select learning modules with content most relevant to their interests and immediate needs. Or provide choice in instructional formats such as readings, videos, narrated presentations, podcasts and interviews. With online discussion forums or question and answer sessions you can also offer choice of content for discussion and the method for communication (e.g., written or virtual meeting).

As knowledge and skills advance, offer choices that help farmers manage obstacles they encounter during learning. You can do this strategically on an individual or group basis. For example, if you notice a group is stuck on a problem and members are getting frustrated, you could offer them the choice to take a break, start over, consult with another group, pick a different problem or use additional resources. As farmers become more advanced, motivate them to excel even more by offering choices in the types of problems to solve, how they would like to receive feedback, or ways in which they can share their knowledge and skills with others. When working with an individual farmer, ask them to explain their choices as a way to promote more self-awareness.

The profile “Giving Learners Control in an Extended Train-the-Trainer Project” illustrates how two educators offered choice in content, process and outcomes to participants at three key points in a train-the-trainer course.

Adult learners can assess their own growth and their peers’ with self-tests, skills practice and reflective journals. You may not find it feasible to offer learners choice in outcomes in brief learning events, like an hour-long webinar or a conference session. In longer events or programs that involve multiple meetings over time, either in person or online, giving participants choice in how to demonstrate their growth and accomplishments can be very rewarding and enhance their drive to continue learning after a formal program is over. In long-term events and programs, choices for learners may include:

- Demonstrating a skill and getting feedback from peers and the instructor

- Designing an original case study or scenario and explaining how they resolved it

- Developing “self-quizzes” with answer keys for peers

- Keeping a record of their efforts and results using new strategies or skills to share for feedback

Wrap Up

When you incorporate opportunities for adults to make choices about their learning, even in small ways, you create a learner-centered environment that fosters engagement, motivation and ownership.

Some educators feel their job is done if they have “covered the content” with little regard for learners’ experiences, knowledge or accomplishments. This teacher-centered approach is often characterized by educators using just one or two teaching methods, like a lecture and slides, and limited ways to assess learning outcomes. When you incorporate opportunities for adults to make choices about their learning, even in small ways, you create a learner-centered environment that fosters engagement, motivation and ownership. In the next section we provide more ideas about how you can offer learners choice in content, process and outcomes.

How to Apply the Best Practice

Strategies for offering choices in content.

- Conduct an online learning needs assessment prior to an event or program. Provide a list of topics or skills and ask farmers to indicate their priorities. Use this information to customize your curriculum.

- Review the agenda at the beginning of an event and again at break points for longer events. Invite feedback about changes farmers may want.

- During a learning event, provide opportunities for farmers to break into small groups for discussion or learning exercises based on content preferences, or to rotate among a few different groups of their choosing.

- For a learning exercise, prepare a few different scenario problems and let farmers choose which one they would like to work on.

- Ask farmers to choose a situation, problem or enterprise from their farms to use as their example in practice or problem-solving exercises. If personal examples will be used as a group exercise, then recruit volunteers who are willing to share ahead of time and give them the option to keep their example anonymous.

- In a multi-day workshop, put up a list of topics after lunch on the first day and let each farmer select a topic. Ask each individual to become the “resident expert” on that topic and to prepare a single poster sheet of topic highlights learned during the event, to be presented on the last day. For review and wrap up on the last day, put posters on walls and let participants walk around to read, comment or ask questions. This strategy can be modified for an online course, where participants post their topic highlights on a bulletin board or wiki document.

- In an online course with components or modules, such as multiple areas of farm law, allow farmers to choose the modules most relevant to them and work on those first, leaving other components for later study as needed.

Strategies for choices in process.

- Before a learning program, provide a variety of online resources and let farmers choose which ones to review. This could involve reading articles, visiting websites or blogs, following a Twitter feed, watching videos, or working through a simulation.

- When you prepare your materials for an educational program, be ready with a variety of presentation formats (e.g., slides, videos, reading materials, sample equipment, models, simulations, etc.) and a variety of activities (role playing, case scenarios, short quizzes, student-led discussions or question and answer sessions, problem-solving, etc.). During a program, keep attuned to engagement levels and be ready to offer alternate formats or activities, either to all participants or to subgroups, if applicable. Offering the option to switch things up can stimulate interest and motivation. Even an alternate method or activity lasting just 2–5 minutes is enough to get participants re-engaged.

- During an in-person event, give farmers choices in how they can record their experiences and document their learning. Offer paper and pens for note-taking and/or diagraming. If appropriate, allow participants to audio or video record portions of the event.

- Make slides available online after an in-person event. If an in-person event is recorded, provide a link to the recording after the event. If a webinar, record the session(s) and provide a link to the recording(s).

- If your program involves providing feedback to farmers about their learning, give them a choice about the feedback process (e.g., verbal and/or written, individual or group, in person or virtually, peer feedback or instructor only).

Strategies for choices in outcomes.

- In multi-day programs, in person or online, offer choices in how learners demonstrate their growth in knowledge, skills and/or values. Examples include:

- In a question and answer session, offer the options of having a participant read aloud the response from a peer or of partners sharing their answers with each other.

- Provide time for written responders. For those who write their responses, offer the option of having a peer read aloud a response.

- In a skills demonstration, let farmers choose the order in which they demonstrate.

- If you need to assess growth in knowledge and/or skills via a standardized test, you may not be able to offer choices in testing mode. However, in helping farmers prepare for a test, offer a variety of formats to self-test or test peers, such as generating questions and possible answers, written or oral quizzes, demonstration, video recording responses, etc.

- If you are working with an individual farmer over time, offer choices in how they demonstrate their growth in knowledge, skills and/or values. Depending on the learning goals, options could include:

- Demonstration of skills

- Business records

- Research project records

- Personal written, audio or video journals

- Graphic drawings or concept maps

- Verbal description of how problems were identified and decisions were made

- Question and answer session

Review Questions and Reflections

- Fill in the blanks in this sentence:

- When individuals are presented with a __________, a network in the brain responsible for processing __________ is activated. Simply having a __________ activates this network, and when a __________is made, the network reinforces the perception that what was chosen feels like a __________.

- List four ways choice positively impacts adult learning.

- Reflect on an experience you have had as an Extension educator when a group of learners did not seem very engaged. If you could do it over again, how would you incorporate two opportunities for the participants to make choices in their learning to improve their engagement?

- Think about an upcoming learning event or program you are working on. How, specifically, could you offer the participants a choice related to:

- The content they will learn

- The processes or methods they will use for learning

- The outcomes or ways they can demonstrate their learning or growth

Profiles

Giving Learners Control in an Extended Train-the-Trainer Project

Ellen Mallory and Tom Molloy, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Ellen Mallory and Tom Molloy led a train-the-trainer project on soil health that integrated opportunities for choice throughout, putting the participating service providers in control of their learning in the following ways:

- Early on, participants could choose to join one of three cropping system-focused teams (potatoes and grains, dairy or mixed vegetables).

- Participants could then sign on at their preferred level of commitment: as a core member, who received technical and financial support and committed to either working with at least one farmer per year on an on-farm demonstration trial or developing an educational resource such as a case study; or as an associate member, who helped identify needs and participated in their team’s educational events.

- As learning progressed, teams could choose how they used what they were learning to support farmers. Through team meetings they identified farmers’ needs and planned on-farm demonstrations and educational resources to meet those needs.

Importantly, throughout the project, Mallory and Molloy provided customized support for each team, including advice on demonstration ideas and design, on-the-ground assistance establishing demonstration plots and collecting data, coordination of cover crop seed orders, distribution of announcements for field days and farm tours, and inter-team communication.

For more information

SARE project: Strengthening knowledge, skills and networks for soil security in Maine (2017)

Read more: https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/neme17-001/

Offering Choice Through Agenda Review

Seth Wilner, University of New Hampshire Extension

Seth Wilner thinks offering adult learners choices in their learning is critical. Assessing needs during planning and then designing the program agenda and facilitation strategy based on those needs is an important first step, but only a first step. Wilner also reviews the agenda and seeks agreement on it as part of every workshop. “That’s essential in my opinion for getting buy in and encouraging participants to take ownership,” Wilner says. “I want to provide the opportunity for the participants to tell me if I got it right—if the agenda looks like it’s going to address the reasons they came. Maybe there is a missing topic or, for example, maybe we should discuss one topic before another.”

Whenever possible, Wilner makes adjustments according to feedback. For example, when teaching agricultural service providers at a weekend event, there were four major topics to be covered: effective adult education principles, leadership and communication, labor management and practical applications of whole-farm planning principles. Wilner led with the basics of adult education but then gave choice on both the order and the length of the remaining session topics. The participants, by majority decision, rearranged the agenda and shaped the event to meet their needs. Along with determining the agenda topics, participants also chose the activity type, be it small-group, large-group or individual learning activities.

Wilner also revisited the agenda at break points to check how everyone was doing, to look ahead at topics and time remaining, and to ask if the plan still looked good. When he does this at his educational events, he often receives requests for change. While it gives participants a sense of ownership, Wilner notes there can be challenges to this approach. If there are other educators or content specialists involved in the program, then revisions can be more difficult because the changes they request can sometimes be focused on topics that are too narrow or in depth. Facilitators also must be adept enough in the content area to be able to make adjustments on the fly, and confident and secure enough to decline to make an adjustment when there is a good reason not to, such as when they are not prepared to address a requested topic or when the change would deviate too far from the stated focus of the event. In this situation, they should share their reasoning.

Offering Choice When Assigning Content and Outcomes

Sidney Bosworth, University of Vermont Extension

When Sidney Bosworth led a training series to help farmer educators and advisors improve their knowledge of pasture weed and forage plant identification, he incorporated choice to help drive home the information.

Through hands-on, in-person training retreats and follow-up webinars, participants first built a solid foundation of knowledge about weed and forage species, growth cycles, plant characteristics, and management strategies for weed control or optimizing yield and quality of forages. Then, as part of the learning plan, Bosworth asked each educator to choose a weed or forage species of interest and develop a helpful fact sheet about the plant’s identification, growth characteristics and management considerations in pastures.

By developing fact sheets on plants of their choice, participants translated their learning into a useful collection of resource materials for farmers and other educators. Bosworth offered participants an additional choice in outcome from their learning: the opportunity to apply for a small amount of funding to offer an educational workshop or similar learning opportunity for farmers about pasture weeds and forage plant identification and management.

Bosworth advises that participants need support from the facilitator, such as a template for fact sheets, assistance finding information sources and coaching before a workshop, to follow through successfully on applied projects such as these, and it is important to budget adequate time to provide this support.

For more information

SARE project: Professional development project in weed and forage identification and management (2014)

Read more: https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/ene14-130/